When Gethin Matthews, a senior lecturer in history at Swansea University, discovered the existence of 100 or so letters written by three brothers – Richard, Gabriel and Ivor Eustis – to family back home in Swansea during the First World War, he knew they were something special. Not only did they feed into a research project he was working on, but the siblings were related to him. However, among the letters was one that he found deeply unsettling.

“I’ve always been interested in Welsh history, so it’s natural for me to want to know how my family fit in. I’ve amassed a lot of information on all of my lines: 15 of my 16 great great grandparents were Welsh, and one is of Cornish ancestry – the Eustis branch.”

Gethin’s initial area of academic interest was the Welsh overseas, but his focus has been on the Welsh during the First World War for the past decade. “Back in 2010, no Welsh historians were looking at the war, so I thought I’d build up my expertise in the area as we headed towards the centenary.”

He knew of the three brothers – his grandfather’s cousins – but didn’t know any details about them. In fact, he had no idea that they’d served in the First World War until 2010. “I was running a project with the aim of getting material out of Welsh family archives and digitising it.” A few years into the project, a serendipitous meeting brought a stash of letters to Gethin’s attention.

“Quite by chance in 2015, I met a chap called Ian Eustis and we discovered that we are quite closely related; he was my father’s second cousin. One day Ian said to me, ‘I’ve got something I think will be of interest to you.’ And he came to see me with a box containing 100 letters written by the three brothers during the war.” It was a real ‘wow’ moment for Gethin: ”In all the work I’ve been doing, it was very rare to find a family that had preserved more than a dozen letters – it was all very exciting.”

Priceless correspondence

Gethin set about studying the missives. “Because they were so detailed, the brothers’ personalities came through. You got to know their relationships within the family, and how they changed as individuals between 1914 and 1918. To be able to track all that through the four years of the war was fantastic.”

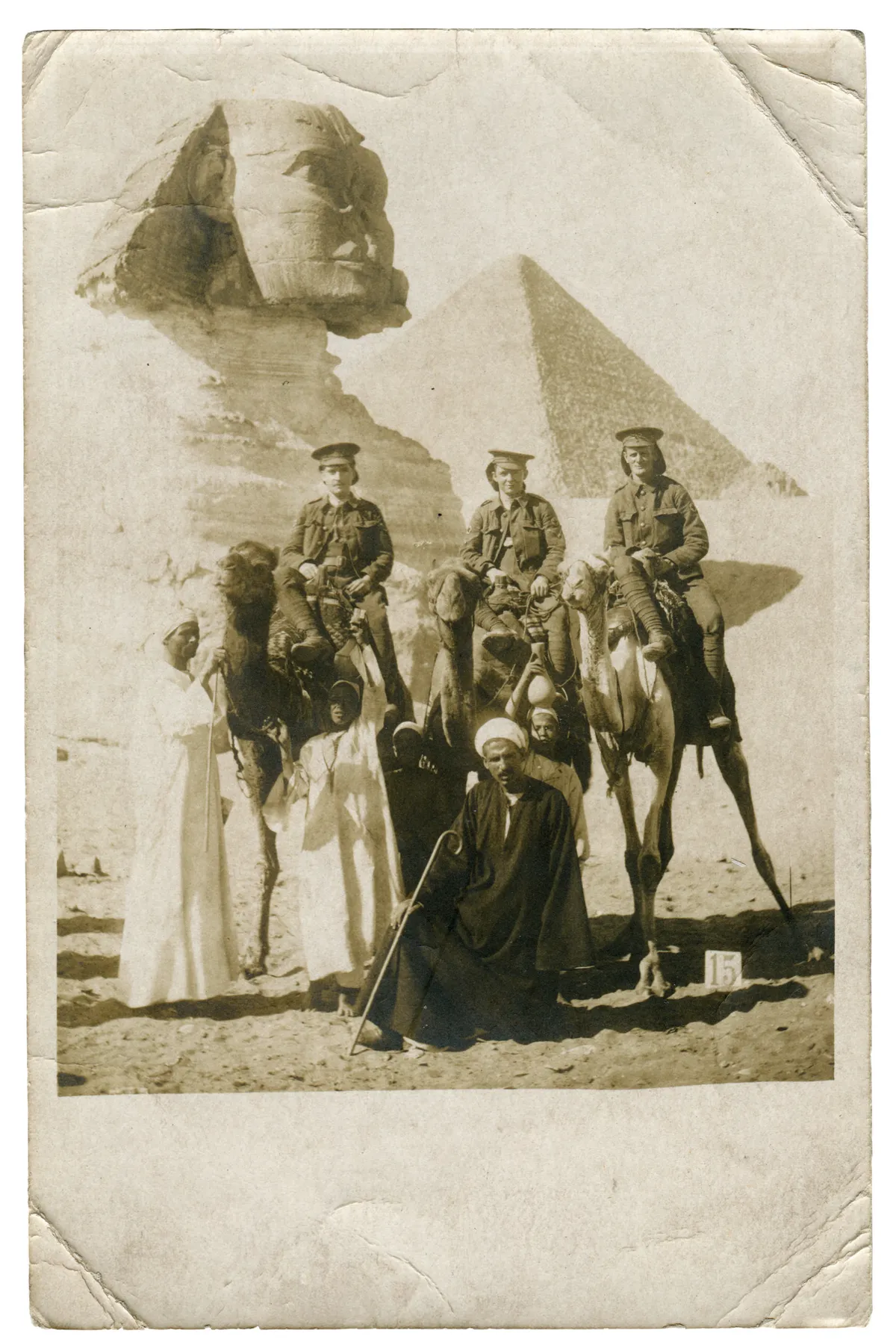

Richard (born 1893), the eldest brother, was the first to join up. He and his friends had enlisted in the Welsh Field Ambulance Unit in 1913, seeing the two weeks’ training at a camp in Aberystwyth as a kind of paid holiday. “They were in the camp in July 1914, so they were literally already in uniform when the war started.” In theory they had a choice whether to become regular soldiers, but the friends all joined up together. Richard’s unit was sent to Gallipoli and from there to Egypt. They then followed the fighting through Palestine – including at the Battle of Gaza (1917), where he was a stretcher-bearer.

Before the war, Gabriel (born 1895) had a job in a tinplate works in Morriston, north Swansea. “Gabriel joined up on 7 November 1914 and became a wireless telegraph operator, and served on a converted trawler HMT Saxon, which patrolled the North Atlantic. They were the eyes of the Navy, looking out for submarines or enemy shipping. He served on the boat until the end of the war.”

The youngest brother Ivor (born 1897) was very bright academically. He was conscripted in 1916 shortly after his 18th birthday, and joined the Royal Welsh Fusiliers. “Because he was such a good teacher, instead of being sent straight to the trenches, he stayed at the camp in North Wales as an instructor for a year,” says Gethin. Ivor was sent to the Western Front in December 1917. “He won the Military Medal, and was promoted to sergeant.” In August 1918, at the beginning of the Hundred Days Offensive that ended the war, shrapnel from a shell blast lodged in his temple. He was invalided back to Wales, and awaited demob in Ireland.

While Ian’s letters were a godsend for Gethin’s research, the collection wasn’t complete. However, by using other sources Gethin could cross-reference the contents and fill in some gaps.

Relations provided postcards and old photographs. One of them had Gethin confused for a while. “It’s a photograph of Gabriel wearing a soldier’s uniform, and Ivor wearing a sailor’s uniform.” They’d swapped clothes before the picture was taken. “It tells you a lot about their fraternal bond.”

Gethin also turned to the National Library of Wales’ free online resource, Welsh Newspapers. “Two of the Swansea newspapers have been digitised, so I was able to pick up a lot of information about many of the people who were mentioned in the letters. It’s just fantastic!”

A community's courage

Rolls of honour from local chapels showed those who had enlisted with Richard. “You could see the whole community’s commitment to the war – so many families had sons who went to fight in Egypt or Palestine.”

Unit diaries on Ancestry and the website of The National Archives at Kew also provided details that the letters often had to omit.

“Another source I was lucky to get access to is Richard’s personal diaries for 1916 and 1917, which had been in the care of his granddaughter. I compared the information in his diaries with his letters.” For instance, the diaries include vivid accounts of his experiences during the First Battle of Gaza in 1917. On 26 March he writes, “Carried patients about 10 miles back to base, arrived there at 3.30 p.m. Had to leave some wounded behind. Pitiful. Crying for us from all sides, but couldn’t see to them as we had a loaded stretcher. Never felt so tired in my life.”

The diaries also make it clear how much the letters sent to and from his mother and sisters mattered to Richard. “He’s holding onto his civilian identity through this lifeline and this connection to his home.”

He notes that the letters between the brothers are different to the ones they wrote to their parents and sisters. “This shows that there were different levels of conversation happening. The letters home were very rarely explicit about fighting, principally because they don’t want their families to know what it’s really like. These letters are not about them as soldiers – they’re about them as sons or brothers.”

Unsolved mysteries

Perhaps because of this self-censorship, frustratingly the details of a couple of key events are missing from the letters. Gabriel’s ship rescued another vessel that was being attacked by a U-boat and saved many of the crew, but he doesn’t mention it. “We also don’t know exactly why Ivor was awarded the Military Medal. He obviously got it for doing something courageous, but I don’t know what.”

At the end of the war, the letters dry up – Richard returned from Egypt, Gabriel came back from the North Atlantic, and Ivor went off to university in Bristol.

Gethin pulled all the strands of his research together to write a fascinating book called Having a Go at the Kaiser: A Welsh Family at War, which gives a rich and multi-layered insight into his relatives’ wartime experiences.

But there is one letter in Ian’s collection that Gethin found particularly troubling. “It was so emotional. I didn’t know who it was from, so I left it until the end of the process – when I was getting everything together for the final chapter of the book.”

It was a vaguely remembered family story, and a distant relative – a chap called Dave Gordon, who contacted Gethin – that eventually helped to unlock the letter’s meaning. The missing piece of the puzzle was the name of Ivor’s sweetheart: Ellen Cranfield. The letter was from her to Hannah, one of his sisters.

The shrapnel in Ivor’s head finally killed him one May day in 1920. Gethin recounts in his book how “the fragment of shrapnel moved. He underwent a procedure in Bristol hospital to try to remove it from his temple but he died on the operating table on Sunday, 16 May. His brother Gabriel had to travel to Bristol to recover the body.”

Ellen’s letter was dated the day after Ivor’s death. “Inconsolable in her grief,” says Gethin in his book, “she wrote a few lines, ending ‘no one knows or understands how much he meant to me. Can’t write anymore.’ – the ‘t’ at the end of ‘meant’ has been superimposed over an ‘s’.”

Of all of the letters in Ian’s collection, Ellen’s perhaps most accurately expresses the terrible toll of the war. “It was such a powerful letter. I could see what Ivor’s death meant – not just to the family, but to all the other people who loved him. There is a real sting in the tail of this story,” concludes Gethin.