Tracing German ancestry has become a lot easier now that so many records are coming online. Although most Germany migrants headed to America, many of them also came to the UK. When George I, the Elector of Hanover, came to the British throne in 1714, he was followed here by large numbers of Hanoverians and Brunswickers so you may have German ancestry that came over to Britain over three hundred years ago.

The 18th and 19th centuries saw a huge influx of German-speaking immigrants from all sectors of society so you may have German ancestry when you don't expect it. These included bankers and merchants, who came to the City of London, such as the Rothschilds and Barings; artists – Angelika Kauffmann and Johann Zoffany; musicians like Sir Charles Hallé, founder of Manchester’s Hallé Orchestra, and the numerous German bands that played in British cities in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

German ancestry: Occupations

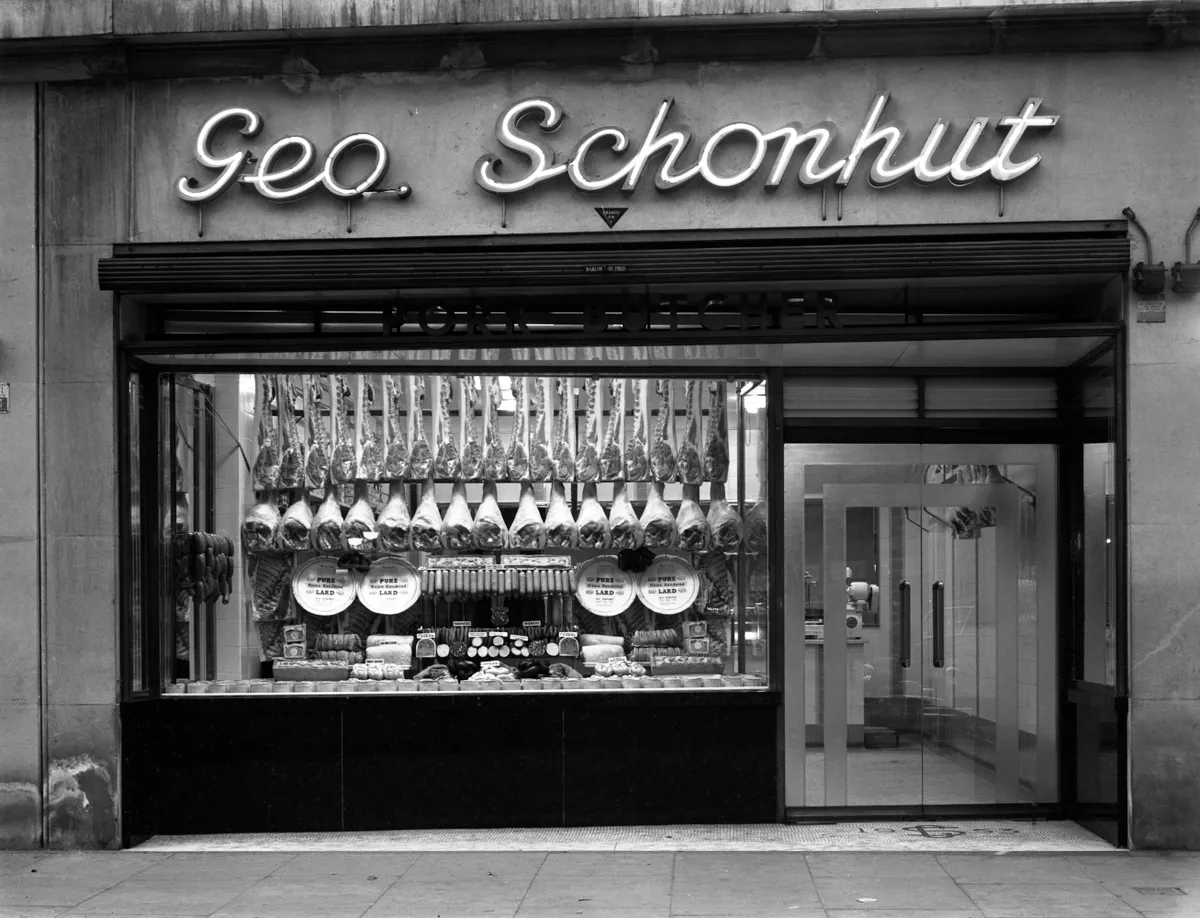

As well as merchants, bankers, artists and musicians, there are other occupations that you may come across in the census records if you have German ancestry. There were also craftsmen such as piano makers, cabinet makers, tailors and furriers; shopkeepers, particularly hairdressers, pork butchers and bakers; sailors, soldiers and even labourers – especially in the sugar refining industry, which was largely German-owned, -run and -manned until the mid 19th century.

Sometimes your German ancestor's occupation can give you a clue as to where they came from. Sugarbakers usually came from western Hanover, Bremen and Hamburg, pork butchers usually came from Hohenlohekreis in north east Württemberg, street musicians from the Palatinate (West Pfalz), clock and watchmakers from the Black Forest in Baden and soldiers in the King's German Legion from Hanover (initially, at least).

Germany as a state did not exist until the German Empire was formed in 1871. Until then, the German-speaking parts of Europe were divided into many separate states ranging from the tiny Schaumburg-Lippe and the city of Hamburg to major European states such as Prussia. The European wars over the previous 100 years led to many smaller domains being incorporated into larger ones.

As Prussia conquered less powerful regions including Hanover, Schleswig-Holstein, and much of Hesse in the mid 19th century, many of their citizens fled to Britain. The crack-down by the rulers of the larger German states on the attempt to set up a democratic German Confederation in 1848 also led to many political refugees – among them Karl Marx – fleeing to London.

The inpouring of poor Central European Jews from the 1880s onwards, however, did not include many Germans; most came from Russia. It was in the 1930s that German Jews, escaping from the Nazi threat and the Holocaust, started coming to the UK.

If you're interested in researching your German ancestry, the Anglo-German Family History Society or the Jewish Genealogical Society of Great Britain should be your first port of call.

German ancestors: Why did they settle in the UK?

But why did they come here? Until 1914, there were few controls over immigration. People could set up in business anywhere they wished and Protestantism, the faith of many of the incoming Germans, was openly accepted in the UK.

Also, Britain was the centre of the Industrial Revolution and the Empire, which meant there was a growing market and demand for willing and skilled workers. But in many cases – especially in the mid 19th century and the 1930s and 1940s – the principal reason to come here was to escape tyranny.

German ancestry: The best resources

Town and local archives

There are large numbers of records kept in local archives in Germany, which should gladden genealogists' hearts.The organisation of these varies in different parts of Germany but look for the local Stadtarchiv or town archive to start with. If there isn't one, try the local Kreisarchiv or county archive. With all German research it helps to know where your ancestors came from, especially as European borders changed over time. A useful website to try and place the parish or town that your German ancestors came from is Meyers Gazetteer.

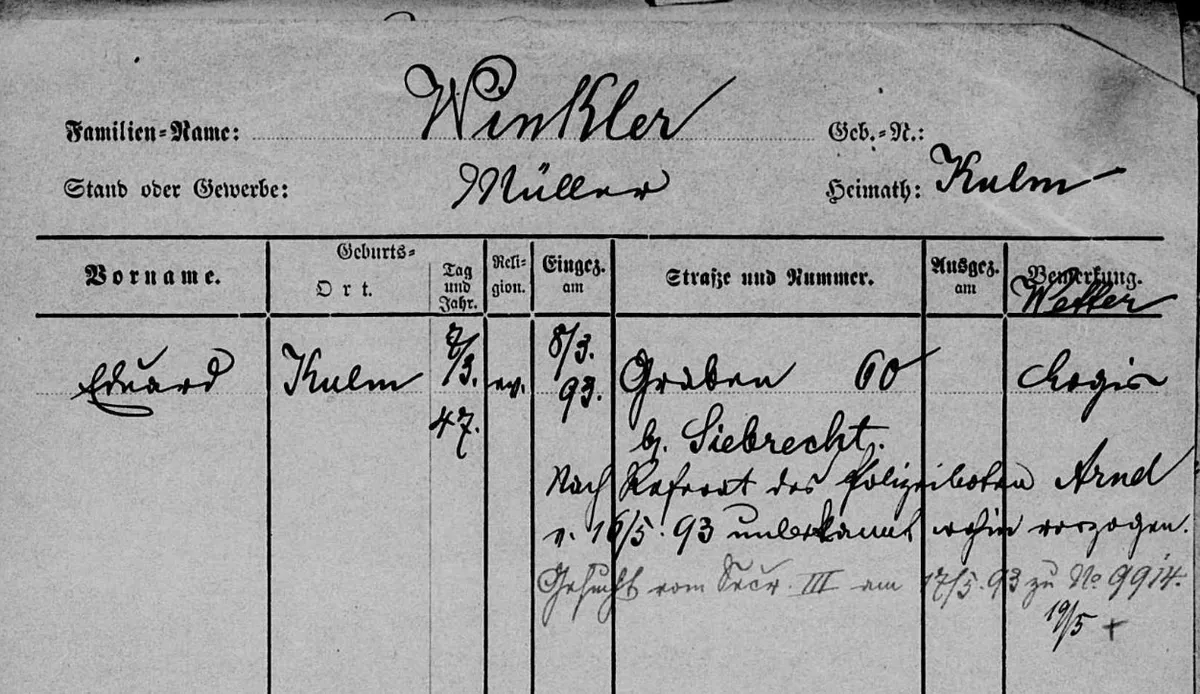

The kind of information a local archive may hold includes detailed records of everyone who lived in the town or village. These Einwohnermelde (inhabitants' listing) records were required to be kept from 1876, though many areas have similar records from much earlier; Leipzig holds them from 1811. The records (on cards) list each family, where they came from and went to, their politics and even any suspected criminal activities. Many of these have been filmed by FamilySearch and are gradually making their way online.

There are no national census records, but many individual states did hold headcounts similar to the British censuses at various times. Few are indexed. The 1819 census for the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, however, is particularly detailed and has been indexed by the Immigrant Genealogical Society in the USA. Population registers for Kaiserslautern in Bavaria from 1793 to 1919 can be browsed online for free at FamilySearch.

A very useful source in the former Kingdom of Württemberg is its Familienregister or family registers/tables. By legislation in 1807, the local Catholic priest was required to keep a detailed register of everyone living in the parish – whatever their religion. This recorded everyone alive in 1807 – organised by family – and lists, with dates, the birth, marriage and death of everyone.

The Familienregister also holds records for immigrants to the parish including where they had come from, as well as where anyone leaving the parish went to. So it could include family details back to the mid 18th century! Most of these have been microfilmed by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) Church and there is a helpful online guide to how to use them. You can access the Familienregister and other similar family registers from the region on Ancestry and Archion.de.

City directories or Adressbücher can also be useful and MyHeritage has put a large number of these online as has Ancestry. The website for Germany's largest family history society Verein für Computergenealogie also has a large collection of Adressbücher that are free to browse online. FamilySearch are also planning to put their collection online in the near future.

As each town or city in Germany has a unique administrative history, it is worth asking what other goodies your ancestral archive may hold. You never know! The Rhineland-Palatinate State Archives have recently together to put material online via their new virtual reading room, APERTUS where you can search a range of records including an emigrant database.

German Church registers

Germany was more or less 50/50 Catholic and Protestant after the 30 Years War ended in the mid 17th century.

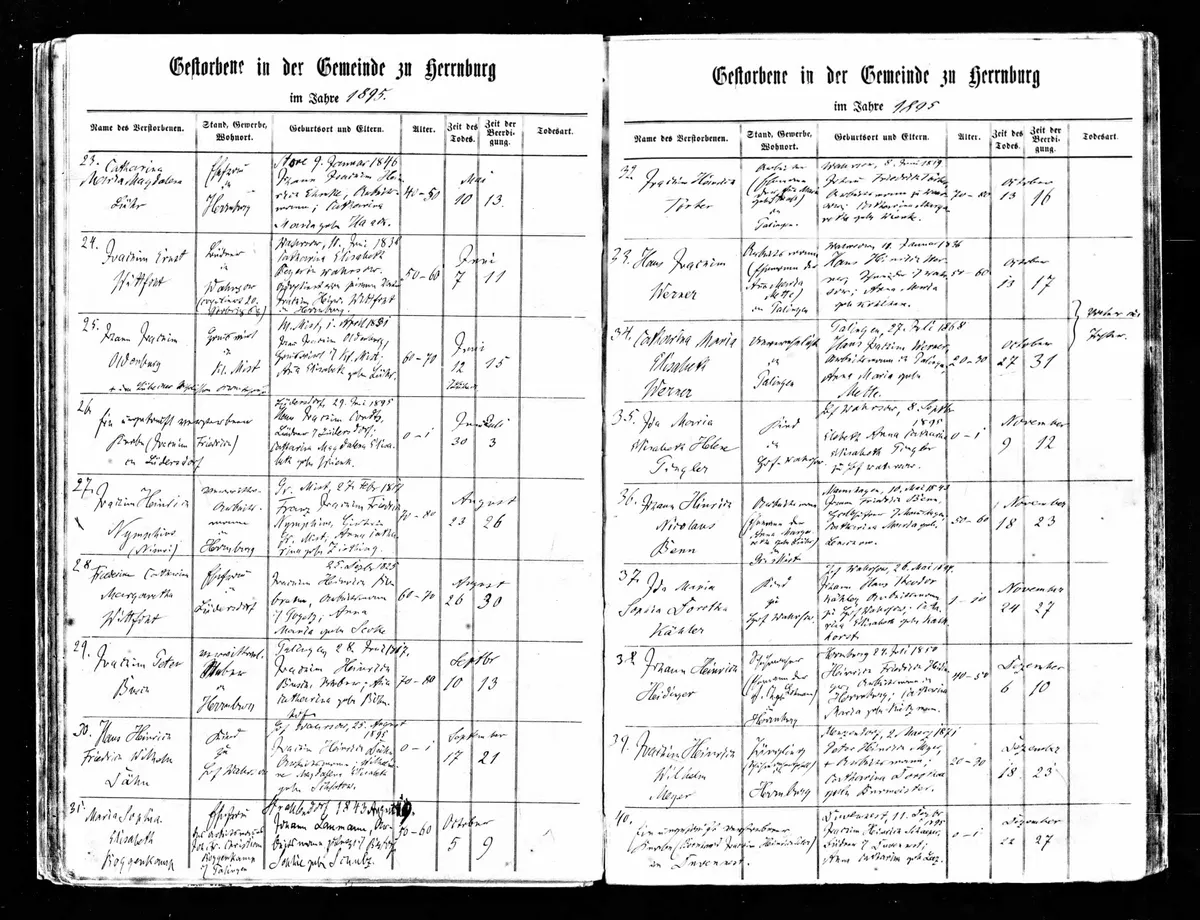

Most parishes will have registers or Kirchenbücher that go back at least that far; though some have been destroyed in wars, fires and other disasters. Some are still in the parish but most will be in the local archives or, especially for places now no longer in Germany, in one of the specialist church archives. Millions of pages of Protestant parish registers are available online via Archion.de. This is a pay-for site and the registers are not currently indexed so you need to know where your ancestors came from. The site has an English option, including a useful tutorial on reading old German script.

Ancestry also has a large collection of German Kirchenbücher, especially for Württemberg with over 50 million records from 1500 to 1985. MyHeritage also has a growing collection of German church records including registers from the former province of West Prussia (now Poland).

The entries are usually very much fuller than you would find in the equivalent English register. In a baptism record, you will normally find both parents' names, places of origin and the father's occupation. Marriages will give even more information.

Many parish registers both Protestant and Catholic have been microfilmed by the LDS and many have now been put online at FamilySearch. Some of the records, such as the Catholic records from the Archdiocese of Freiburg im Breisgau, have been digitised but only the index can be easily viewed online. To see the actual images for this and some other collections you have to access them from a Family History Centre or a FamilySearch affiliate library.

Another useful site for anyone researching Catholic ancestors is Matricula which has digitised Catholic records from across the old Austro-Hungarian Empire with a large collection covering Germany.

There were several German Protestant churches in Britain from the 17th century onwards, and a Catholic church in London from the 19th century. The surviving registers have been indexed by the Anglo-German Family History Society although they are not yet currently available online. Many entries say where the immigrant came from in Germany sometimes at parish level. Church records for St George's German Lutheran Church in Whitechapel, London have been indexed by FamilySearch.

German Civil registration

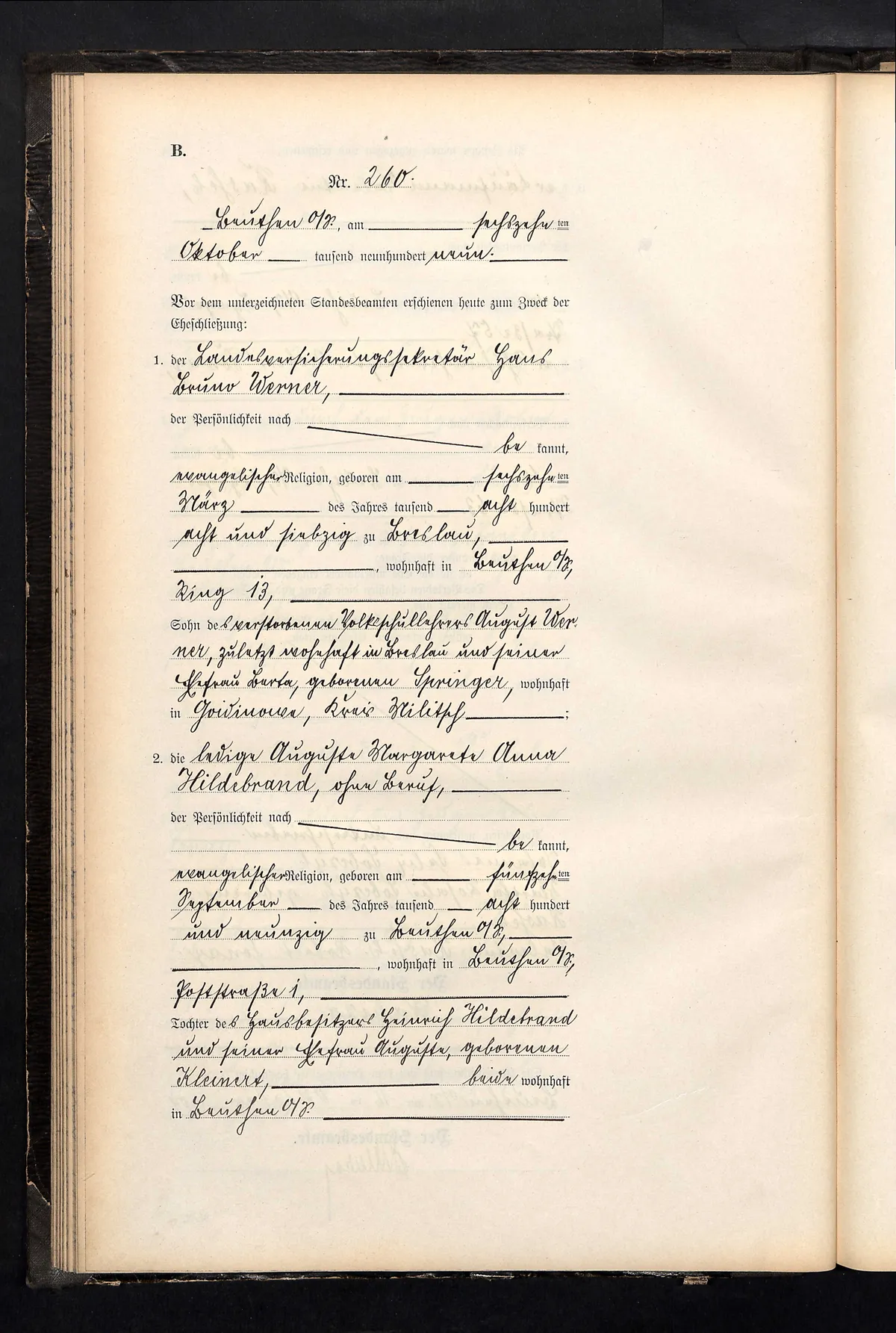

There are no national indexes of births, marriages and deaths in Germany. All records are kept in the local civil registration office, the Standesamt.

As Germany was not a single state until 1871, civil registration began in different areas at different times. In Bavaria, it started in 1876; in much of Prussia in 1874; and in the areas influenced by France during the French Revolutionary Wars – such as the Rhineland and Baden – in 1792.

If you are not sure when it started in your area, you need to ask. The earlier records are very detailed, but later German certificates are only as informative as English ones. Only proven direct descendants of the person registered are allowed copies of more recent certificates but later vital events (birth records over 110 years old, marriages over 80 years and deaths over 30 years) can be viewed by anyone and more and more are now going online.

Ancestry has civil registration records for Hesse (1851-1985) and Nuremberg (1876-1983) among others and FamilySearch also has some of these collections.

World War German internment

At the outbreak of the First World War, the UK had a large German population – particularly in London and the other principal ports.

Men of fighting age, roughly 18 to 50, were interned from 1914 to 1919. They were kept in camps around the country, but mainly at Douglas and Knockaloe (near Peel) in the Isle of Man.

The Knockaloe Museum has an excellent new website with a large collection of documents and photographs of internees and the museum is generally happy to help individuals with their research.

Most First World War British records of internment were destroyed by bombing during the Blitz. However, the International Committee of the Red Cross holds returns of all internees in both wars and should be able to provide you with details, including their date and place of birth, for a fee. The First World War records held by the ICRC have recently been digitised, although they haven't been fully transcribed so searching can take a while.

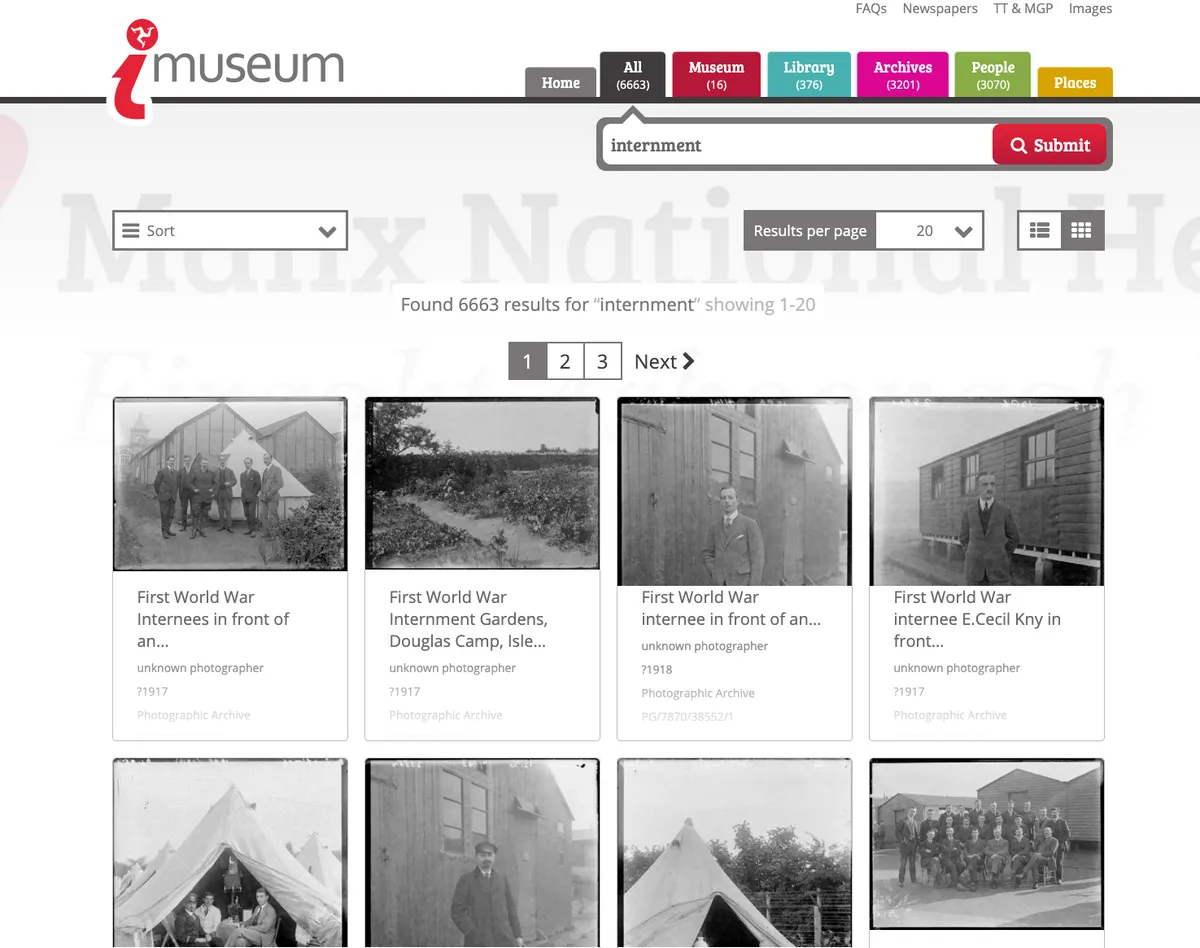

Surviving records of internees held on the Isle of Man have been indexed and can be searched via the excellent iMuseum website where you can also view images from the camp.

For the Second World War the British records are at The National Archives (TNA) at Kew and include records of each enemy alien taken before a tribunal to determine whether they were to be interned or set free. Again, these include the date and place of birth. Surviving TNA records for internees of both World Wars can be searched via Findmypast.

Emigration documents

Most German states required those who wished to emigrate to first obtain official permission.

The individual had to show they had performed their military service, their parents were dead or adequately provided for and that all debts had been settled.

Even then, permission was not automatic. Many just chanced their luck and left – especially those who did not want to do their national service or were avoiding the political police. If they did request permission, their details should be in the local archives under Auswanderung (emigration).

There are no records of passengers leaving Germany or other North Sea ports except Hamburg and then only from 1850 to 1934. This information is available on Ancestry.

Many immigrants naturalised in the UK after some years – especially in the late 19th or 20th centuries. However, the proportion doing so was tiny up to 1914. The process was expensive and not necessary to stay here.

Those who did naturalise will have given their date and place of birth and their parents' names and you can find these details on their naturalisation certificate and in their Home Office file at The National Archives at Kew.

German Military records

Sadly for researchers, the German and Prussian Army and Navy records were all destroyed in the Battle for Berlin in 1945.

Some military records of the formerly independent states, such as Hanover (pre 1867), Hesse (pre 1867), Bavaria (pre 1919), Württemberg and Baden (pre 1919), are kept in the relevant state archives.

Probably the best collection of surviving records online is available on Ancestry and includes military directories recording almost six million military and marine officers as well as Bavarian personnel rosters from the First World War and First World War casualty lists.

When the Electorate of Hanover, George III’s home state, was conquered by Napoleon, the former Hanoverian Army escaped to England where they were reformed as the King's German Legion (KGL) in the British Army.

The full records are partly at The National Archives and partly in the archives in Hanover. They cover 1806-1815 and include many volunteers from other German states who fought the French invaders. The Anglo-German Family History Society has indexed most of the KGL records held by TNA and can supply details on application.

Visiting Germany

Before you go to Germany to search for the records of your ancestors, you must know exactly where they came from.

You can use British sources to get that information – naturalisation records; German churches in the UK often recorded the place of origin of members; internment records; obituaries; military records; adverts in the local and trade press; and family papers. You can look up places mentioned in the records on Meyers Gazetteer or Kartenmeister if your ancestors came from eastern Prussia.

Before you go, check which archive or archives the records are held in; what the opening hours are and whether they are open to the public. In some cases – for example, in Bremen – you may be better off going to the offices of the local family history society, Die Maus (the Mouse), as it holds copies of many records – saving you countless trips to many small village archives.

If you do not speak German or have problems with reading the script, you will need expert local help. You should contact the archives and ask if there is an English-speaking researcher willing and able to help.

On the other hand, if you know your family came from a village or small town, try contacting a local historian or newspaper there. You will probably find large numbers of cousins happy to welcome you 'home'!