"The main facts in human life are five: birth, food, sleep, love and death.”

This quote, attributed to the novelist EM Forster, sums up the ‘vital’ evidence that we seek when attempting to piece together the remains of our ancestors’ lives.

Evidence regarding the first of these facts can sometimes be tricky to trace. If you're having trouble finding details of a forebear's birth, scroll below for five expert tips that may help you break down your brick wall...

1. Be aware of informal name changes

Boris Johnson's ancestor, Osman Wilfred Kemal, Anglicised his name to Wilfred Johnson

It was (and still is) perfectly legal for people to change names without officially informing the authorities. One of the most frequent causes of confusion is the habit of interchangeably using first and middle names; a man known as George William Newman on all other records may have been christened William George Newman.

High rates of illiteracy meant some people weren’t certain how their name was spelled. I struggled to locate a birth certificate for my ancestor James Berry until I experimented with spelling variants and wildcards, and found it registered as ‘James Bury’.

A completely different name could have been adopted intentionally. Boris Johnson’s father knew that his grandfather Wilfred Johnson was actually born ‘Osman Wilfred Kemal’, and raised by his maternal grandmother Margaret Johnson who Anglicised his name. Without this vital piece of inside information we would have struggled to find his birth certificate, so it’s worth asking extended family what they know.

If you already have an idea of the mother’s maiden surname then look under that if an initial search fails.

2. Try searching a different quarter

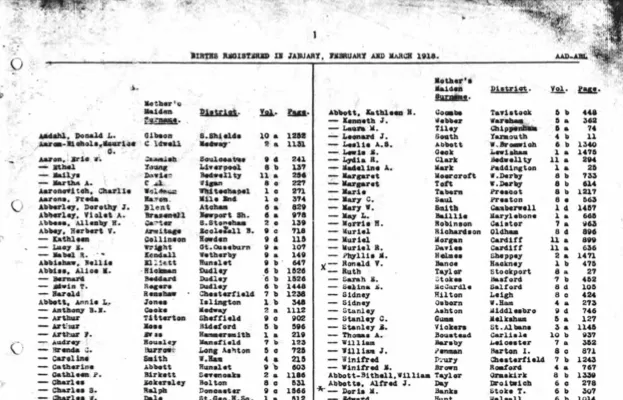

Your ancestor's birth may be registered in a different quarter to the one you might expect

So you know your relative’s date of birth, yet you can’t find their birth certificate. Until 1984, the GRO birth indexes for England and Wales were organised quarterly, after which time they were arranged annually. Perhaps the birth you’re looking for is there, but it wasn’t registered in the same quarter that the child was born, as parents had 42 days to register a birth.

For example, although I was born in September, my parents didn’t get around to registering my birth until October, therefore my birth appears in the October-December quarter instead of the July-September quarter where I thought I would find it.

Dates of birth can be discovered on death certificates issued from 1 April 1969 onwards. However, the information is only as reliable as the person who provided it, which is usually whoever registered the death, so consider whether an error could have been made and alter your search parameters accordingly.

3. Common name? Order a sibling's certificate instead

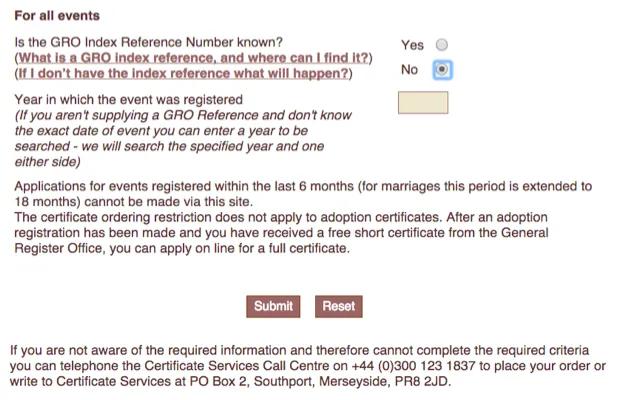

Not certain you've found the right person when ordering a certificate? You can request a three-year search for a certificate matching specific criteria, such as parents' names

Rather than finding nothing at all, with surnames like Smith and Jones there are endless possibilities. Ordering certificates for siblings with less common first names is one way around this. Pay close attention to where they lived and focus your search on the registration districts covering those areas.

The place index at UKBMD reveals that births in Abenhall were registered under Westbury-on-Severn until 1937, after which they came under the Forest of Dean district.

The GRO order form asks ‘Is the GRO Index Reference Number known?’ If you’re not certain you’ve found the right person, click ‘No’ and request a three-year search for a certificate matching specific criteria, like the parents’ names. Full refunds are given for unsuccessful searches.

4. Watch out for illegitimacy

When a child was born out of wedlock the birth was usually registered under the mother’s maiden surname. The child may have informally acquired a stepfather’s surname at a later date, and could even have named that man as their father on other documents, causing confusion.

Marriage certificates provide useful information about the bride’s and groom’s fathers, but alas this could be misleading, hence it’s always worth looking under the suspected mother’s surname if an initial birth search fails.

If, like Mary Berry’s ancestor’s children, your forebear was born illegitimately and no father’s name is given on the birth or baptism record, then the chances of discovering the father’s true identity are slim. The mother could name an illegitimate child after their real father, perhaps bestowing his surname as a middle name.

If she applied to the local authorities for financial assistance then they could have investigated his identity, which may be revealed in bastardy bonds and examinations at local archives.

5. Widen your time frame

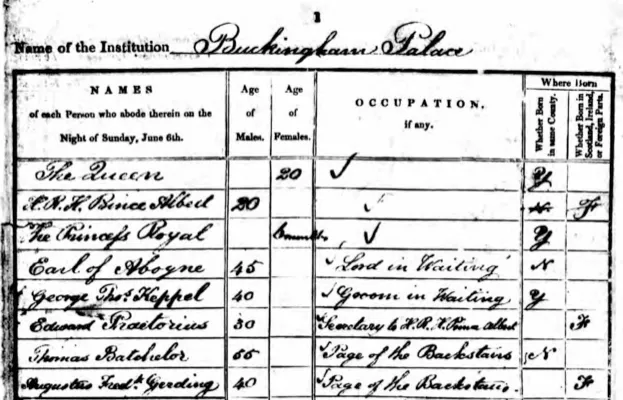

In the 1841 census, everyone over 15 – including members of the Royal Family – was supposed to round their age down to the nearest five years

Our first clue for finding a birth usually comes from the age given on another document. However, like many teenagers during the First World War, Lesley Garrett’s ancestor convincingly lied about being over 18 on his service papers.

People often stretched the truth about their age at marriage to appear older or younger. Some simply weren’t certain how old they were. The earliest census records showing an ancestor at home with their parents may be the most reliable.

However, in the 1841 census everyone over the age of 15 was supposed to round their age down to the nearest five years. Expand the birth search to a decade either side to cover all eventualities.