Actor, comedian, author and talent-show judge David Walliams has put family relationships at the centre of many of his novels, and yet confesses to knowing very little about his own family history. "I now have a family that's my own... but it makes you think often about the family you came from as well. And you think well, actually, I would like to know my place in this story."

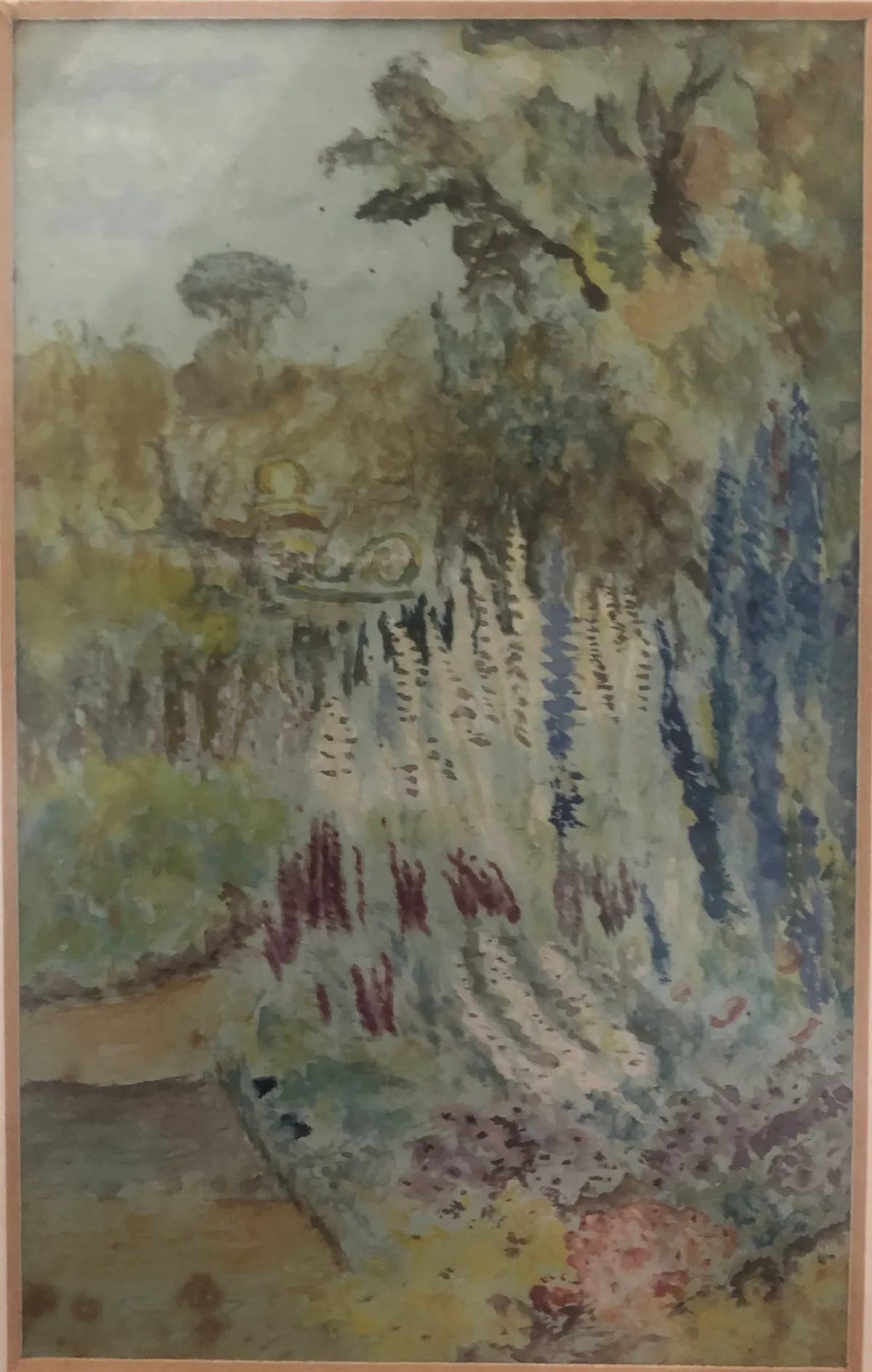

David has three small watercolours that he knows were painted by a relative of his paternal granny Ivy and that the relative had suffered from shellshock during World War One. He knows even less about his maternal side of the family so heads off to Surrey to visit his mum.

At his mum’s he is shown a photograph of his maternal great grandfather Alfred Walter Haines, who had once run a fairground in Battersea, although Alfred’s daughter, David’s grandmother Violet, never talked of her travelling background.

Enquiring about the watercolours, David’s mum tells him that the shell-shocked artist was actually Ivy’s father, John George Boorman.

John volunteered at the start of the war and joined the prestigious Grenadier Guards. His wife Harriet was pregnant with their third child at the time.

David heads off to the Guards Museum at Wellington Barracks in London to meet military historian Jeremy Banning and learn more about John’s time with the Grenadier Guards. That John, a labourer, was tall for the time may account for how he ended up with such a prestigious regiment, but it did not keep him from seeing some of the bloodiest action of the war.

John’s first major engagement was the Battle of Festubert, a real baptism of fire: "So you're a labourer one day and then six months later you're trying to kill someone in a muddy hole perhaps, with your bayonet, with your fist, strangling them, whatever. I mean it's just terrifying."

So you're a labourer one day and then six months later you're trying to kill someone in a muddy hole

John returned to England in June 1915 but was back in France in August 1916 in time to experience both the Battle of the Somme and Passchendaele. Travelling to Belgium, David meets battlefield historian Lucy Betteridge-Dyson at Sanctuary Wood, where there are some preserved British trenches. Here he discovers some of the horrors that John would have experienced.

After appearing in a casualty list for September 1917 John next appears in the records of Napsbury Military Hospital in August 1918.

David travels to the site of the hospital in Hertfordshire where he meets historian Fiona Reid, who shares with him the records that show John had suffered from shellshock after the battle of Festubert. Unfortunately further records show that John’s mental health declined further and he ended up spending the rest of his life at Cane Hill Asylum It was here that he painted the watercolours that now belong to David.

"I'm glad he had the paintings, and I'm glad I've got them,” David says. “I'm glad they're still in the family and hopefully they'll stay in the family forever".

Next David turns to his maternal side of the family. Looking at the marriage certificate for his great grandfather Alfred Walter Haines, he can see that his father William Haines is recorded as blind.

Travelling to Salisbury, David meets historian Julie Anderson at the General Infirmary, where she reveals that David’s great great grandfather lost his sight during a cataract operation in 1884.

By the 1891 census, William is in Portsmouth with his family, recorded as a musician. More details are revealed in a newspaper article that reports William and his wife Julia were charged under the Prevention of Cruelty to Children Act for making their children dance and sing while he played the barrel organ.

However, William’s fortunes were set to change. Following him through the censuses David discovers that by 1911 William was listed as a Travelling Showman. Meeting with historian Jodie Matthews at the site where his family were based in Manley’s Yard, Battersea, David discovers that they would have owned and operated rides and shooting galleries.

Finally, David heads to Maidenhead to see rides similar to the ones owned by his family and to meet fairground historian Graham Downie. Graham shows David an obituary for William that describes him as a successful showman. His wife Julia continued the business after he died and an obituary from the World’s Fair newspaper even includes a photograph of her.

A final photograph shows a group of boys sitting on the edge of one of the rides. It is thought that they are David’s great uncles, his grandmother Violet’s brothers.

As David walks out of the yard he thinks about what he has learnt: "I love my great great grandfather's story. It's a real story of resilience. To lose your sight... to then be working a barrel organ and go on to be a very celebrated showman... I can't help but be proud of him.

I think they're both really inspiring people and I'm so glad their stories have been told

"And I couldn't be prouder of my great grandfather John George Boorman. He fought in the First World War, but sadly he lost his sanity. It's a really, really sad story but I think they're both really inspiring people and I'm so glad their stories have been told.”