The Forth Railway Bridge is known the world over as a marvel of Victorian engineering. Built between 1883-1890 and opened on 4 March 1890, it spanned the estuary or 'Firth' of the Forth near Edinburgh, putting in place a vital link in the direct rail route between London and Aberdeen.

It ended centuries of having to cross the Forth by ferry, with regular delays and the guarantee of 20 minutes of misery in anything more than a stiff breeze.

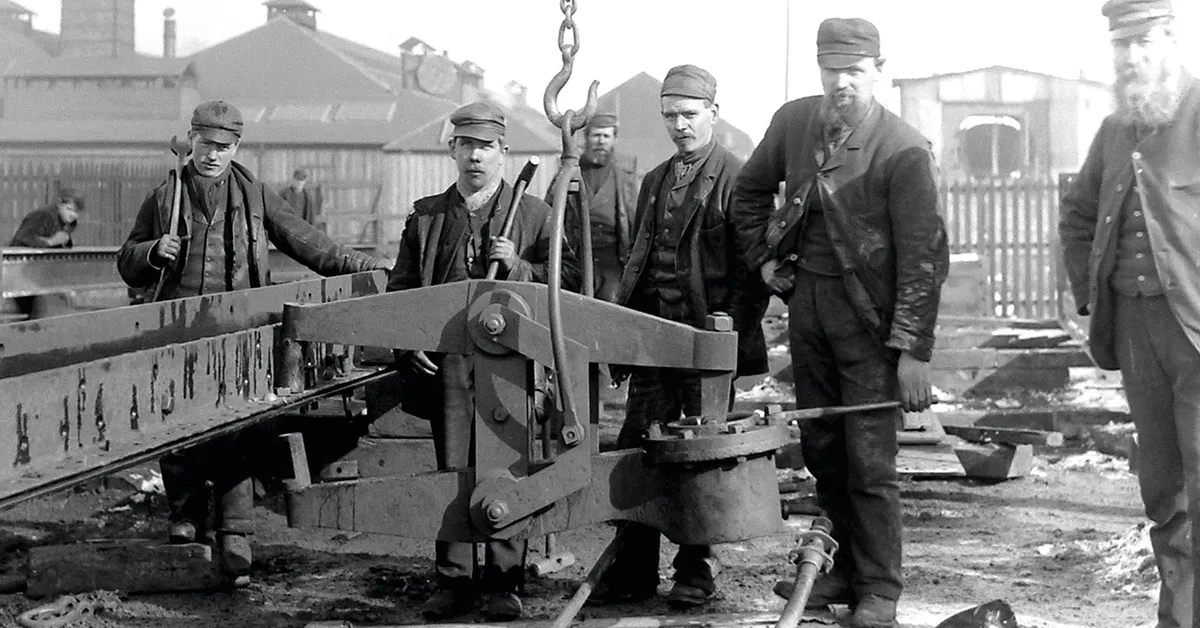

The names of the bridge’s designers – Benjamin Baker and John Fowler – and of its main contractor, William Arrol, who went on to build London’s Tower Bridge, have gone down in history for their ingenuity and skill. What though of the thousands of workmen, the briggers, as they were known, who actually built the bridge? Who were they, what were their lives like and what was the human cost in creating this giant?

On these questions contemporary and later sources were strangely silent. Buried deep within the technicalities of skewbacks and bed plates in his report of 1890, bridge engineer Wilhelm Westhofen made a few tantalising references to the briggers as skilful, cheerful, heedless of danger and not always sober. He also wrote: “Of accidents between July, 1883 and Christmas, 1889, there had occurred 57 fatalities”.

Who were the briggers who built the Forth Bridge?

That figure of 57 construction-related deaths went unchallenged for over a century until the Forth Bridge Memorial Committee was formed in 2005 to campaign for a fitting monument on each side of the Forth to the briggers who had died. Recognition of the courage of the men was more than overdue: their counterparts who died building the Forth Road Bridge had long since been commemorated.

For Jim Walker, especially, the setting up of the Forth Bridge Memorial Committee was a milestone. Growing up within its shadow, Jim had always been passionate about his bridge. He explored every aspect of its history and gave talks to local groups, driven by the desire to recognise the briggers, and most of all those who lost their lives. “As I looked at the bridge I often thought of the briggers working hundreds of feet up there in all weathers. What did they think about as they hammered in those 6.5 million rivets?”, he muses. The Forth Bridge Memorial Committee asked the Queensferry History Group a deceptively simple question: “What were the names of the 57 men?” Four members – Jim Walker, Jenni Meldrum and Len Saunders, later joined by Frank Hay – took up the challenge. Several years of painstaking research later, the team had the answer. At least 73 men could be confirmed as having died during the construction of the bridge.

At first, the team had not anticipated any difficulty in identifying the names of the men. The records of the Sick and Accident Club, an early form of insurance against injury and death that the briggers were required to join, would list them. Despite an exhaustive search, however, no trace of the records could be found. By now, however, the team’s mettle was up.

Initially progress was frustratingly but unsurprisingly slow as Jenni and Len had full-time jobs. Years of research by Jim had only uncovered 12 names. The detail could be as limited as ‘Anderson 1887’. A stroke of luck accompanied the arrival of Frank, in the form of his sister-in-law, professional genealogist Sheila Hay. She searched for the names in the death certificates held by the General Register Office for Scotland (now the National Records of Scotland). “I drew a blank: nothing matched. A gang of family historians used to meet for lunch and when I mentioned my difficulties, fellow family historian Ian Stewart had a eureka moment – ‘Why not try searching for some Irish names?’.” Contemporary sources claimed that a third of the workforce was Irish.

Finding the names of the men who died building the Forth Bridge

Ian’s inspiration opened the floodgates – finding names identified the districts where death certificates had been issued. Searching the relevant districts, including St Giles ward where Edinburgh Royal Infirmary was based, produced scores of names and how and where they had died. “It was like being on a roller coaster,” says Sheila. During the six months of research, the mystery of ‘Anderson’ was finally solved. The birth name of the 30-year-old rigger from Germany who fell 200ft to his death, fatally fracturing his skull, was Eugen Julius Weise. Why he adopted the alias, John Anderson, may never be known.

The names were fed back to the briggers team who scoured the national and local press, transcribing relevant information verbatim onto a master list. It included not only accidents and deaths, but also details of town life from water shortages to the scandalous behaviour of the local parish minister. They created a spreadsheet of possible deaths that covered a whole wall in the History Group’s meeting room. At one time there were well over 100 names.

Then the task of checking them began. Even matching names quoted by different sources required significant detective work. In an era of hand-written records, human error was all too easy, even if the clerk was conscientious. Some of the itinerant caisson workers constructing the bridge’s underwater foundations, like Thomas Liberale, possibly did not speak English. It was all too tempting to add his name to the list, despite the cause of death being left blank. Given the time of death at 5.40pm, the Italian diver may have died of caisson disease (the bends), coming up to the surface too quickly at the end of his shift. The team resisted the temptation, relying on proven fact rather than supposition in adding names to their list.

To include or not to include? The team decided to extend the list to men who had died after the Sick and Accident Club was wound up at the end of 1889, but before bridge maintenance began. This added another seven names to the list including George Fowler. Thanks to advances in medical knowledge, we can now be sure that the ex-soldier whose death certificate of 1892 recorded “supposed heart disease”, in fact died of the bends. He had spent seven years as a brigger, two of which as a caisson worker. Although he managed to work on despite complaining of aches and pains, he was in such poor physical and emotional shape by spring of 1890, that he refused to go to the workmen’s dinner after the official opening.

His son left a note explaining why. “He was very tired of that bridge and didn’t care if he ever saw it again. He had had enough.” That note passed down the generations. Frank recalls his excitement on opening an email from a Jim Magnuson. “It turned out that he was George’s great grandson, now living in the States. He traced our research through a website and got in touch. His family still talks about ‘The George Fowler Memorial Bridge’.”

After much heart-searching, the team closed the list at 73 confirmed deaths, at least until more concrete evidence emerged of other possible casualties on their shortlist. As a member of the Forth Bridge Memorial Committee as well as of the research team, Len was proud to hand over the list of names. “At last we could move on to the next phase of raising funds for the memorial now we had names to put on it. It was a long haul but good fun along the way, meeting regularly in a local hotel to pore over our latest findings and argue the toss about who to include or exclude.”

Was there a cover-up over the Forth Bridge death toll?

There is a significant difference between the official figure of 57 deaths on the bridge and the researchers’ total of at least 73. People often claim that there was a cover-up and that, at the time, management considered the cost of human life to be cheap. In 1888-89, the sheer number of accidents and deaths resulted in a press campaign against the carnage. William Arrol pointed to the root of the hysteria: “There are no more accidents here than in an ordinary ship-building yard but as there is only one Forth Bridge, and as everything that takes place on it seems to get reported in every newspaper in the country, people get quite erroneous ideas about the fatalities that do occur”.

The researchers found no evidence of a conspiracy to disguise the deaths. On the contrary, William Arrol was a caring employer, identifying closely with the briggers and devising machines and procedures to make their work safer and easier. He knew what life was like from the bottom up, having started out, aged 10, in a textiles mill. The main reason for the discrepancy in the figures is that the researchers included deaths associated with bridge construction such as the initial painting in 1890 and the building of the railway approaches. The latter was managed by a sub-contractor and thus excluded from the official tally.

First fatality of Forth Bridge

The researchers’ work established some new, albeit unenviable, claims. On Tuesday 27 November 1883, Thomas Joseph Harris earned a footnote in history as the Forth Bridge’s first fatality. The 16-year-old storekeeper was last seen, as dusk fell, standing well out on the nearly completed, 2,200ft jetty where he had been working. There was no-one to witness his fall or hear his screams as most workmen had left for the night. In the coming days, local fishermen and the crew of the work boats dragged the river in vain. Thomas’s grieving father, bridge works foreman Frederick Harris, finally registered the death on 20 December. Another month passed before Thomas’s body, so decomposed that it could only be identified by its clothing, was discovered washed up on the shore.

The youngest casualty may have been 13-year-old rivet catcher David Clark. Some time about midday on Thursday 13 September 1888 he missed his footing and fell over 150ft, his body bouncing off the ironwork. He died instantly from a fractured spine and skull. The oldest victim of a serious accident that the team identified was 67-year-old Thomas Sinclair, who fell 50ft from the scaffolding. He broke his left leg and dislocated his right knee joint as well as suffering severe internal injuries. His accident is likely to have ended his working life.

What was it like to be a brigger?

During the research, the team amassed a significant amount of information about the lives of the briggers, their working conditions and what they did in their spare time. Bringing the briggers and the town that they invaded to life, was the part that Jenni, as a social historian, enjoyed best. “Suddenly the men seemed to be real individuals rather than just statistics. They worked hard and they played hard. All the hours that I spent pouring over dusty old ledgers in the city archives or deciphering the writing of a police constable, paid off.”

So what was the everyday life of a brigger like? No first-hand accounts have yet been uncovered and no two individuals’ experiences would have been alike, but a lot of circumstantial information can be gleaned from the existing evidence. Many briggers were married with families, and a large number of briggers’ families lived in the working-class area of Leith, Edinburgh’s docklands. Briggers would have risen as early as 4am to catch one of the special Forth Bridge workers’ trains. The fares for the train were deducted from workers’ wages by the office clerks that William Arrol employed.

The ferry crossed to Inchgarvie, the island in the Forth where one of the cantilevers rested, where workers would meet up with their team mates. Riveting was one of the main posts that briggers were employed in. The youngest member of a rivet team was the rivet boy, who would be in his early teens, whose job it was to heat the rivets until they were red hot. He would then removed the rivets with tongs and throw them to the holder-on who placed each rivet into its hole. He would then ‘hold it up’ with a hammer, while the two other members of the team struck it home with several rapid blows.

The riveters were paid by the number of rivets hammered home, a precarious source of income, although riveting meant a lot more money in your pocket than labouring in the docks. Did the rivet boy see his job as a great adventure or did he dislike heights? They clambered up ladders and along walkways to reach their work platform. These were strung one above the other like flats in a multi-storey block, each one home to a team of briggers. Old tweed jackets, mufflers and caps helped to keep out the worst of the weather, but offered little protection against falling tools or red-hot metal.

Facilities for briggers were limited to say the least. During the lunch break, a man was employed to heat up food on a stove and, as there were no toilets, the briggers must have relieved themselves over the side.

The Hawes Inn was the destination of choice at the end of working shifts, its door being visible from where they worked. At peak times, the bar man would line up 200 pints on the counter in readiness. The Inn inevitably became rowdier as nights progressed, and men are recorded going outside to settle an argument or heading to other pubs along Queensferry High Street. A typical brigger however, would, or should, have been back with his family in Leith.

What was it like living near the Forth Bridge?

One spin-off from the research was to shed new insights into the impact of the briggers on the sleepy communities at both ends of the bridge. As the monster rose from the waves, residents realised that their open views of the estuary were gone for ever and housewives complained about smuts on their washing. Some houses in North Queensferry ended up almost literally under the bridge with the thunder of trains overhead disturbing their peace from 1890.

During construction, a more serious cause of disturbance came both from the briggers and the thousands of tourists who poured off the excursion boats. The police had anticipated trouble by doubling the size of the police station before the briggers arrived: nonetheless they had to build a temporary police station close to the works in 1885. Most crimes – breaches of the peace, assaults and affrays – were probably fuelled by drink. As a ferry port, Queensferry already boasted the second highest number of licensed premises in Scotland in proportion to its population. At first the briggers could buy drink in the works canteens where, on Sundays, ministers fought to win their souls among the beer fumes. Under pressure from the law, the contractors later agreed to sell each man only one pint per meal.

Business boomed, housing being in such short supply that rents rocketed. Royal visits brought crowds from Edinburgh and Fife with money to spend, culminating in the festivities around the opening of the bridge by the Prince of Wales on 4 March 1890.

What then? By that time, most of the briggers had left. The giant works that had sprawled over the hillside, its lights burning through the night, were dismantled and the land returned to farming. Edinburgh’s Evening News gloomily predicted: “The ancient burgh, which has been roused from its previous lethargy by the presence in its near vicinity of the great structure, with the necessary accompaniment of its army of workmen and legion of visitors, may be fated to return to comparative oblivion with the completion of the work.”

This prediction proved to be wrong. Ever since 1890, tourists have added the Forth Bridge to their Scottish itinerary. It also won a place in the hearts of residents such as Frank, Jenni, Jim and Len, whose curiosity about the bridge and the briggers led to years of research and the publication of The Briggers: The Story of the Men Who Built the Forth Bridge. Thanks to Evelyn Carey’s contemporary photographs and today’s advanced digital techniques, for the first time the faces of individual briggers can be seen as they emerge from the shadows of their bridge.

The next time you cross the Forth Bridge by train, do not simply marvel at its structure. Spare a thought for the briggers, especially those who died for their bridge.