A dancing craze gripped the youth of Britain in the decades after the First World War. On a Saturday night, the office clerk, shop girl or factory worker could step through the doors of the local ‘palais’, with its glittering chandeliers, fountains and inviting expanse of polished floor, into a more romantic world. In the 1950s, it was estimated that 70 per cent of couples met at a dance hall so it’s very likely that many of us have parents or grandparents whose courtship began with a foxtrot or waltz.

Before the 20th century, organised social dancing was mainly the preserve of the gentry. In the 18th century there were lavish balls in grand houses and dances in assembly rooms, elegant public venues such as the famous Bath Assembly Rooms frequented by Jane Austen. Dancers took part in group ‘country dances’, and etiquette required a formal introduction before a gentleman could ask to be added to a lady’s dance card. That’s not to say that the working classes didn’t dance; they doubtless did in taverns and at fairs, but were constrained by a lack of both leisure time and cash.

Through the Victorian age, dancing opportunities increased for the new middle classes at private clubs, afternoon tea dances in the ballrooms of large hotels, and events run by dance schools. And by the beginning of the 20th century, purpose-built dance halls began to spring up in seaside resorts, attracting a wider social spectrum – the iconic Blackpool Tower Ballroom familiar from Strictly Come Dancing opened in 1899. But it was after the First World War that the dancing craze really started to take off, with the economic boom meaning that the lower middle and working classes had more disposable income to spend on leisure.

This period also saw the birth of the mega dance hall, the grandly named ‘palais de danse’. The first was London’s famous Hammersmith Palais, which opened in 1919. It could accommodate 2,000 dancers on the huge maple floor, housed a café and restaurant, and was luxuriously decorated in the Chinese style popular at the time, with lacquered pillars, a fountain and silk lanterns. For a cheap ticket, you could dance to US big bands and might even rub shoulders with a celebrity guest.

Soon palais of varying sizes appeared in cities and towns around the country. They featured sprung dance floors surrounded by a viewing balcony, and opulent décor with gilding and chandeliers. Larger palais had facilities such as restaurants, ladies’ ‘boudoirs’ or dressing rooms, and perhaps even an on-site hairdresser. Enterprising businessmen soon established chains, the most famous being the Mecca and Locarno, which attracted more custom by opening their own dance schools.

Approximately 11,000 dance halls and nightclubs opened between 1919 and 1926, although not all were as grandiose as the palais, and dances also took place anywhere with suitable space, such as in village halls, schools and workers’ clubs. Music was live; it was the ‘swing era’, and British groups played their own version of the big-band jazz sweeping the USA, with even the smallest venues managing to muster a few musicians. Even through the Great Depression of the 1930s, people kept dancing, although dance-hall owners found it harder to turn a profit.

The social mores of the day dictated that it was the men who did the asking, except when things were spiced up by a ‘lady’s choice’ dance. If a girl turned down an offer, she was expected to sit out the rest of that dance, which must have been galling if she was then approached by a handsome chap she’d had her eye on. Some dancers took their pastime very seriously, attending dance schools and looking askance at those who just muddled along. In 1941, Modern Dance and Dancer magazine grumbled about “the selfish dancers of today, barging into everybody, kicking their feet about, laddering stockings and bruising the legs and feet of other couples”.

Many of the older generation and establishment figures disapproved of the trend. Dance halls often employed skilled male and female dance partners who could be hired for a single dance or per hour, and in some less respectable venues these likely offered more than just dancing. But it was often the dances themselves that provoked moral outrage. This had been a recurring theme since the waltz arrived in the 1820s, with its scandalous requirement that couples embrace on the dance floor. A century later, the flailing limbs of the Charleston were seen as vulgar and sexually provocative. But the underlying issue was that the dance, and others such as the foxtrot and quickstep that came after it, had their origins in jazz music and black US culture.

By the late 1930s, it was estimated that two million people went dancing each week. Attendance was particularly high among single, working-class women, although some of them continued to dance after marriage. The Mass Observation survey of 1939 reported a Hammersmith housewife as saying: “In such a happy atmosphere one can forget that Monday is washday.”

Even the outbreak of the Second World War didn’t curtail the fun. The government initially closed dance venues, but backtracked within months when it realised their importance in keeping up morale. Equipped with tin hats and gas masks, people flocked to dance halls and some were fortified with sandbags and doubled as air-raid shelters, with dancers paying 1s to bed down for the night. Modern Dance and Dancer made much of this ‘Blitz spirit’ when in November 1941 a London dance hall was damaged when a bomb landed next door. It told readers how “the pianist shot off his stool. The trombone player’s silver instrument flew from his hand across the room. ‘Carry on, boys, keep playing,’ said the band leader… Brushing plaster and brick dust from their clothes, the dancers began the Lambeth Walk.” But other dancers were not so lucky. In November 1943, a bomb landed on Putney Dance Hall, killing more than 100 people in the hall and in a bus queue outside.

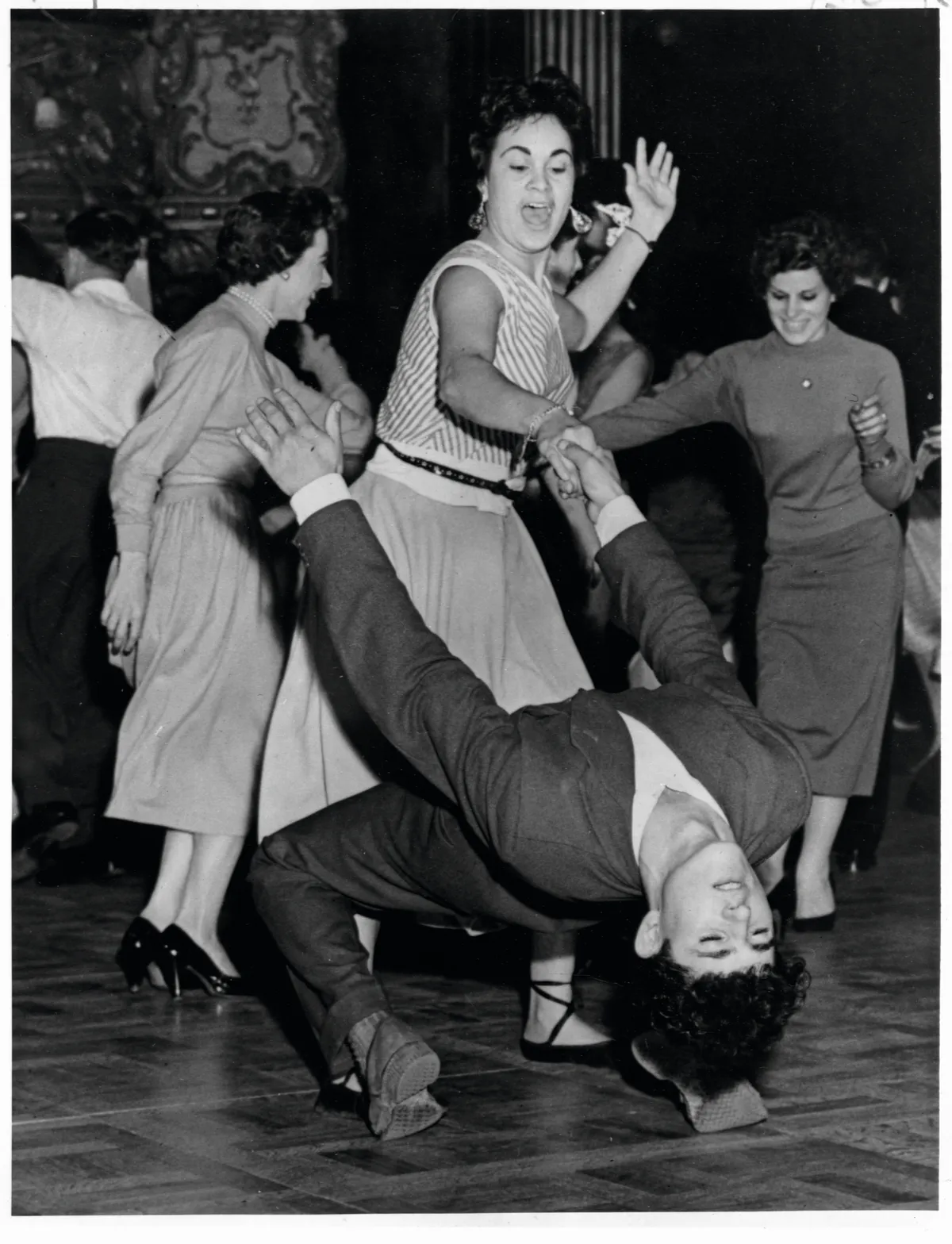

The foxtrot, quickstep, waltz and tango were popular wartime dances, and everyone-join-in ‘party dances’ with simple steps also caught on. The aforementioned strutting Lambeth Walk is one example and another the Blackout Stroll, during which the lights would be turned off leaving dancers to feel around in the dark for a new partner. It was also the era of the high-energy jitterbug. The dance had originated in the clubs of 1920s Harlem, and the British public was already familiar with it from US films. But the influx of American GIs in 1942 popularised it further, and it was soon all the rage. Dance halls hosted displays and competitions in which expert dancers showed off their acrobatic moves, and threw their partners into the air, often flashing their underwear. Moral outrage reached new levels, and some venues even banned the dance.

Racial mixing was also a cause for much hand-wringing, although during the 1920s and 1930s it was not unknown in dance halls, especially those in port cities. Of the three million US troops who passed through Britain during the war, 130,000 were black, and the non-white population was also swelled by soldiers recruited from the Commonwealth.

The US Army tried to maintain segregation of their troops by giving white and black soldiers town passes on different nights and even putting pressure on venues to implement colour bars, with limited success given that this was illegal in Britain. Many British women saw nothing wrong with dancing with black GIs, often finding them less brash and more respectful than their white counterparts. It was a common flashpoint in dance halls, and could result in fights. Although many British men were uncomfortable with ‘their’ women dancing with black soldiers, there was also resentment of the “oversexed, overpaid and over here” Americans, and there were cases of the British siding with black soldiers in clashes with white GIs.

After the war, the dancing population was increased by returning troops and a survey of English life and leisure published in 1951 estimated that there were three million admissions to dance venues every week. The boom years of the 1950s meant a golden age for the dance hall. It was the decade when rock and roll swept the world, and jive – as the jitterbug family of dances became known – was perfect for such fast-tempo music.

But the writing was on the wall for the palais. Rising incomes meant that people could choose from a more diverse range of leisure activities, so there were more places where young men and women could meet. Vinyl began to replace the live dance band, and there was a growing trend for music to listen to rather than dance to. With the 1960s came the twist and the advent of solo dancing. In many ways, it reflected the increasing freedom of women in society – there was no waiting to be asked to dance, no leader and no follower. Palais began to be turned into discos, concert venues, bingo halls and bowling alleys. Some have been demolished, but many faded Meccas and Locarnos are still standing. Occasionally, you might even hear swing music emanating from within as retro-loving dancers take to the floor in an effort to recapture the fun and glamour of a bygone age.