Society’s current preoccupation with buff bodies might seem like a relatively recent phenomenon, but earlier generations also had their share of fitness fads, celebrity personal trainers, and handwringing over concerns that Britain was becoming a nation of weaklings.

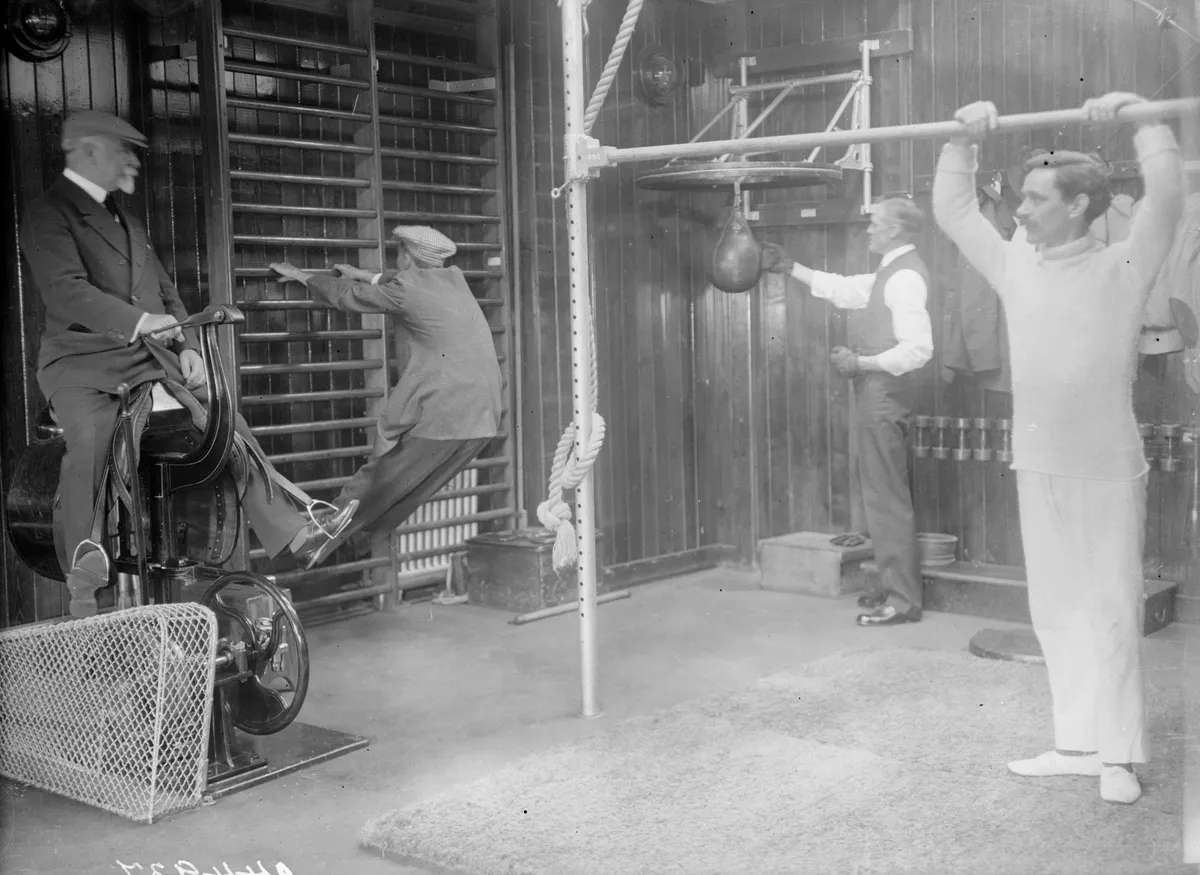

Throughout history, the poor generally got all of the exercise they needed, and more, through hard physical graft, while the wealthier classes had their hunting, cricket and brisk constitutionals. But in early Victorian times, more attention began to be paid to the mechanics of physical training. A cultural trend known as ‘muscular Christianity’ saw physical strength as closely allied to moral strength, patriotic duty and the ability to protect the weak. What’s more, exercise was encouraged as a way to burn off excess energy that might be turned to no good, especially among the young.

There were exercise and leisure facilities aimed at all classes. Probably the most spectacular was the Royal Patent Gymnasium, a huge outdoor facility opened in Edinburgh in 1865 by businessman and philanthropist John Cox. A combination of gym and theme park, it contained traditional exercise equipment such as parallel bars, vaulting poles and springboards along with a giant seesaw, which promised to elevate those on the ends 50 feet into the air, and the Great Sea Serpent, a circular ‘boat’ that allowed 600 people to row simultaneously. Entrance was a very reasonable 6d and, at the height of its popularity, it attracted 15,000 people a day. The gym remained in use until the end of the century, when its declining popularity meant that the site was turned into a football ground.

By the early 20th century, fitness had taken on a political dimension. In a speech at the close of the First World War, the prime minister David Lloyd George warned that if Britain was to be equal to future challenges it must “take a more constant and a more intelligent interest in the health and fitness of the people… you cannot maintain an A1 Empire with a C3 population”, a reference to the fitness categories used to classify army recruits.

Obviously, the most pressing concern was to improve general public health and it wasn’t until the mid-1930s that attention was turned specifically to physical fitness through exercise. In 1937, the Physical Training and Recreation Act was launched along with a National Fitness Campaign to get the population moving and encourage local authorities to provide more leisure and exercise facilities. It was partly a response to the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, where Britain came a disappointing 12th in the medals table. But there was also an urgent need for a physically robust population as the prospect of another world war loomed. Grants for the provision and training of instructors were awarded to organisations as diverse as the Amateur Athletic Association and the English Folk Dance and Song Society, and sports and fitness festivals were organised around the country to promote the campaign.

However, opposition politicians claimed that the legislation was poorly funded and administered, and benefited the middle classes while doing little to address more urgent issues affecting the nation’s health and fitness, such as malnutrition and poor working conditions. “To suggest physical training to a man who for seven and a half hours a day is performing herculean tasks of physical exertion [as a miner] is to talk utter rubbish,” Aneurin Bevan, the future architect of the NHS, argued in a parliamentary debate on 7 April 1937.

In fact, the most important mass keep-fit movement of the decade was the Women’s League of Health and Beauty, which had been launched in 1930 by Irishwoman Mary Bagot Stack. Its motto was “Movement is life” and classes involved a mixture of dance, rhythmic movement and exercises. By 1937, the league had almost 166,000 members and about 50 franchised centres throughout the UK.

It also staged regular public displays that featured large numbers of members performing synchronised exercise routines in their uniform of black satin knickers and sleeveless white top. When one of the earliest events took place in June 1930, a newspaper rather condescendingly reported that “seventy pretty, bare-legged City girls wearing as little as possible were led by two resigned-looking policemen into Hyde Park”. By 1936, the league was able to muster as many as 5,000 members for its annual display at London’s Olympia.

Membership costs were low and the organisation welcomed women of all ages and from all walks of life, often running free classes in deprived areas. It was much more than an exercise organisation too. The league published its own magazine containing articles on self-improvement, feminist debate and pacifism, and provided a social outlet for women with an emphasis on having fun together.

The outbreak of the Second World War soon derailed the Physical Training Act, but it didn’t completely end the drive for improved fitness. The BBC Home Service broadcast two 10-minute keep-fit classes each weekday, and the Ministry of Labour and National Service launched the ‘Fighting Fit in the Factory’ campaign. Its 1941 leaflet recommended walking, swimming and cycling, and reminded workers that “exercise must be a pleasure and not just one more strain. The kind of exercise you best enjoy is probably the kind that will do you most good.”

In subsequent decades, exercise fads have come and gone. But even in today’s world of fitness-tracking devices, sports science, Boxercise and Zumba, the echoes of those early fitness drives still reverberate. The league is alive and well, rebranded as ‘FLexercise’; the influence of muscular Christianity is still visible in the health and fitness facilities attached to many YMCA centres; and the advice to find a form of exercise we enjoy if we’re to have any chance of sticking at it holds just as true today as it did during the Second World War.