When Joseph Brown started selling drapery goods to tailors in 1858, he was “provided with a complete set of new patterns, and a smart horse and trap” and told to “go and prosper”.

“I went out as far as a cold piercing head wind would let me,” he added.

This anecdote gives an insight into the determination of the early commercial travellers.

Commercial travellers developed along with a century in which there was more and more manufacturing, and more shops selling the goods being made.

Another factor was the increase in public wealth from the middle of the 19th century: the public wanted to buy.

Travellers sold exclusively to shops, whose owners had previously gone to warehouses to pick up supplies.

The rise of the trade of commercial traveller therefore corresponded with a decline in that of the warehouseman: when a commercial traveller sold goods, they were delivered to the shop directly.

The occupation column in the census might not simply say “commercial traveller”. The job title given here would often relate to a particular product: for example a commercial timber traveller could be selling lumber or actual standing trees, waiting to be processed when they were bought.

Sometimes they thought it more classy to call themselves ‘representatives,’ so someone could style himself a commercial brewer’s traveller or brewery representative.

The commercial traveller might carry the Commercial Traveller’s Pocket Companion, giving all the counties with the towns and populations of each, their market days and the distance from the main county town.

Travel took so long in the 19th century that a salesman could be away “ten months out of twelve”. He worked one of nine circuits: the South Coast; the Eastern Counties; the Midlands; the Northern Counties; Bristol and the West of England; South Wales; North Wales; Ireland; and Scotland.

Many commercial travellers got started working in a shop. Commercial traveller was a final destination as a job: people did not gain levels of seniority, they just moved on to better companies that dealt in higher-quality (and higher-priced) goods, meaning the commission would be greater when they made a sale. A seller of china dinner services or pharmaceuticals would be on a higher rate than a man seeking orders for buckets and coal scuttles.

Everyone had to have a line in patter, with one salesman quoted as saying: “I am the ambassador, plenipotentiary, envoy extraordinary, from P.B. & Co. The object of my mission to your highness’s court is to settle, in an amicable and equitable basis, the great cotton and linen question.”

Between 1871 and 1881 the number of commercial travellers doubled to 40,000; it was almost 50,000 in 1891.

They would earn £100–200 basic salary a year, but their real income came as commission. This would be on a sliding scale, so there was 2.5 per cent commission on sales from £3,000 to £5,000; 5 per cent on sales up to £10,000; and 7.5 per cent above that. The incentive was great to obtain big orders.

Life on the road

With commercial travellers representing so much money in salary and expenses they were well treated by the hotel trade, who set aside ‘commercial rooms’ where they would write up their order books and dine.

Charles Dickens noted the “hotel-room tapestried with greatcoats and railway wrappers” for commercial travellers. These were effectively club rooms with fellow feeling, in addition to rituals of dining that were almost masonic.

The pretensions of some were mocked by George Formby senior in his music hall song 'The Commercial Traveller': “Everyone says I shine, the fellows in Lockhart’s commercial room say I’m the smartest in my line… I look just like a prize rabbit, I’ve got a wrist watch on and all, I’ll have earrings in next week and you can call me sissy.”

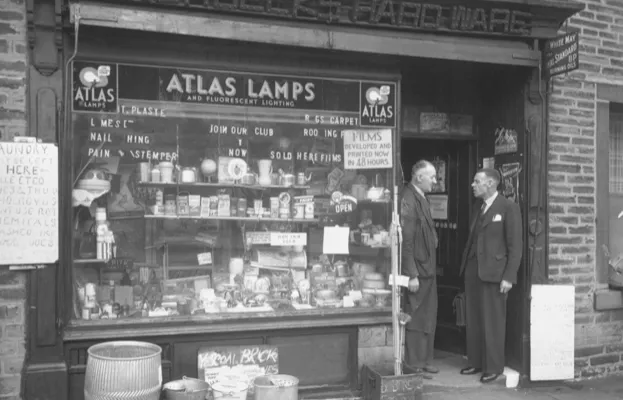

Over the 19th century the traveller on foot or in horse-drawn van became the railway traveller then, in the 20th century, the car driver.

As travel became easier, fewer ate in commercial rooms as more restaurants were available. Travellers returned home more frequently rather than engaging in extended road trips.

There was a temptation to ‘treat’ or buy a drink for a compliant buyer, to ‘baptise the business’. This made heavy drinking one of the dangers of the commercial traveller’s life.

With their self-assured manner, itinerant lifestyle and good income, commercial travellers had a reputation of being popular with the ladies. Certainly a sophisticated man with a car, slick patter and time on his hands in the evenings could play fast and loose with provincial women.

Alfred Rouse was one such commercial traveller and made the news in the 1930s, although he did not become famous so much as notorious.

He worked for a Leicester firm dealing in garters and braces (men wore sock suspenders or garters, and braces for trousers). When his love life started getting on top of him (with two wives and a number of maintenance orders against him) he decided to disappear and start again by killing a tramp who looked like him, putting the unfortunate victim in his car and setting light to it. He was spotted leaving the scene, and was soon arrested.

His trial gives details of the lives of travelling salesmen: he was earning £10 a week; paying £1 12s a week on his car, £1 7s 6d to the building society for his house, and £2 10s a week to his wives for housekeeping.

He had all of the traits useful to a commercial traveller: confidence, talkativeness, social skills and good mechanical knowledge, essential for maintaining the Morris Minor.

But none of these helped him, and he was hanged at Bedford on 10 March 1931.

Where to find commercial travellers

You will see “commercial traveller”, or one of its many variants, in the occupation column of the census, but remember that on census night a commercial traveller would be more likely to be in a hotel or lodging house than at home.

Commercial travellers were a branch of the company for which they worked, and their contact details were included in advertisements in trade magazines.

Willing’s British and Irish Press Guide (which you should find in a county library) will supply the name and date of the relevant trade magazine.

In addition, the Royal Commercial Travellers’ Schools in Pinner, Harrow, educated the children of impoverished commercial travellers and orphans between 1847 and 1967.

Among the resources on their website are a timeline, photographs and memorabilia, while the schools’ surviving records are held at the London Metropolitan Archives.

Finally you can find a range of informative conversations about commercial travellers on the forum RootsChat.