The third series of the award-winning BBC programme A House Through Time aired in 2020 and revealed the history of 10 Guinea Street, Bristol – a three-storey, end-of-terrace Queen Anne-style house built in 1718 by slave trader Edmund Saunders. We showed its fall from housing a single middle-class family with servants into multiple occupation by the 1881 census. My role as the programme’s consultant and on-screen expert is to explore the ways in which the design and material culture of the house changed through time, and how that impacted on the residents. The long-awaited release of the 1921 census of England and Wales in January by Findmypast fills the gap between what we discovered about the house from the 1911 census and the 1939 Register.

How to use the 1921 census to research an address

1. Enter search terms

Click the ‘Find an address…’ tab, and enter the street and the town. The wildcard St* will pick up all variations of ‘street’: st, st., str, etc.

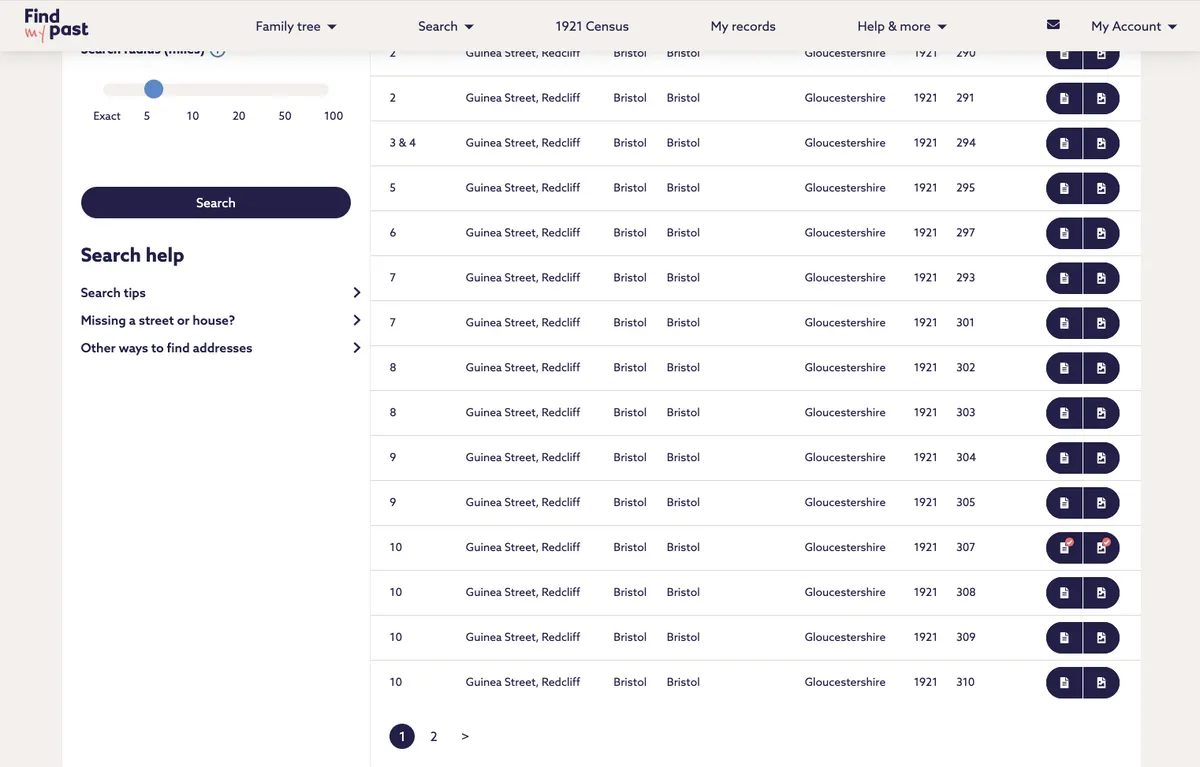

2. Review the search results

From three results, I clicked a street in Redcliff to view the individual households. There are four households at 10 Guinea Street.

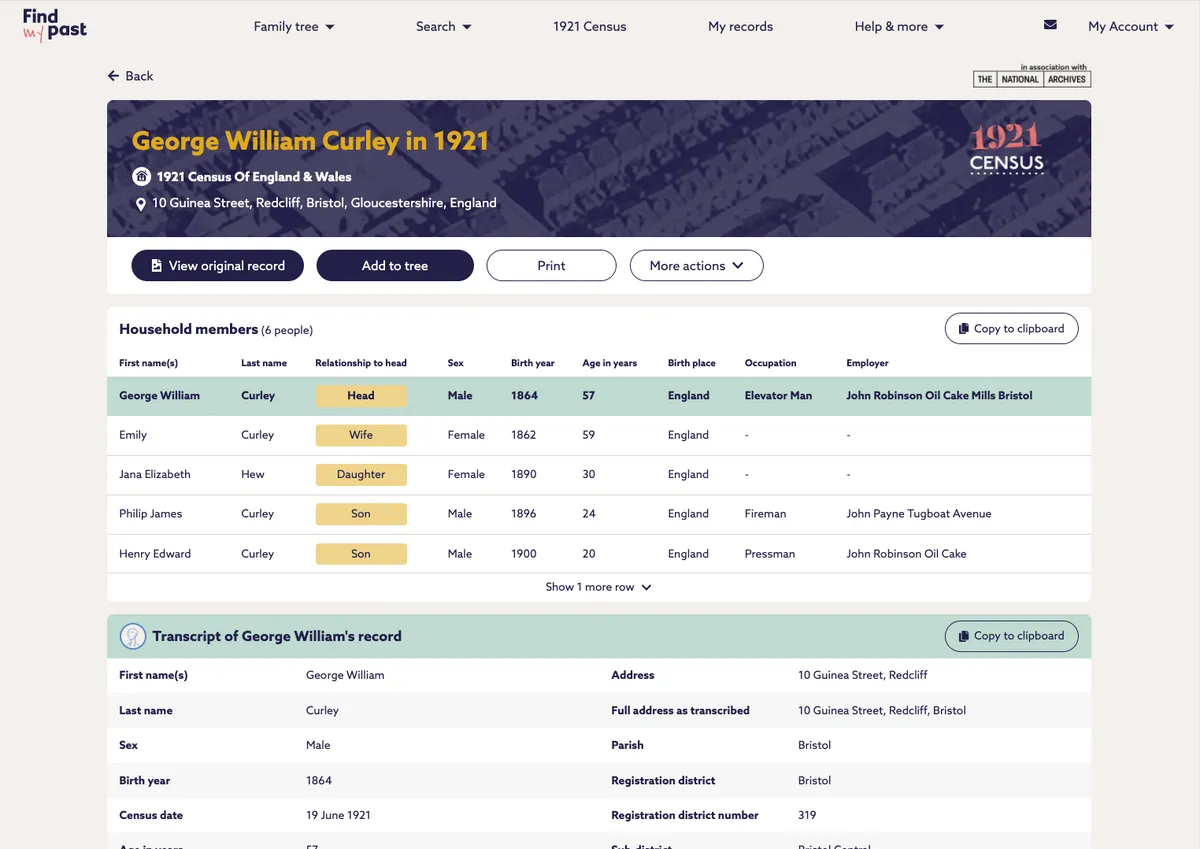

3. View the transcript

The transcript lists every member of the household. Additional information includes a map and a description of the area.

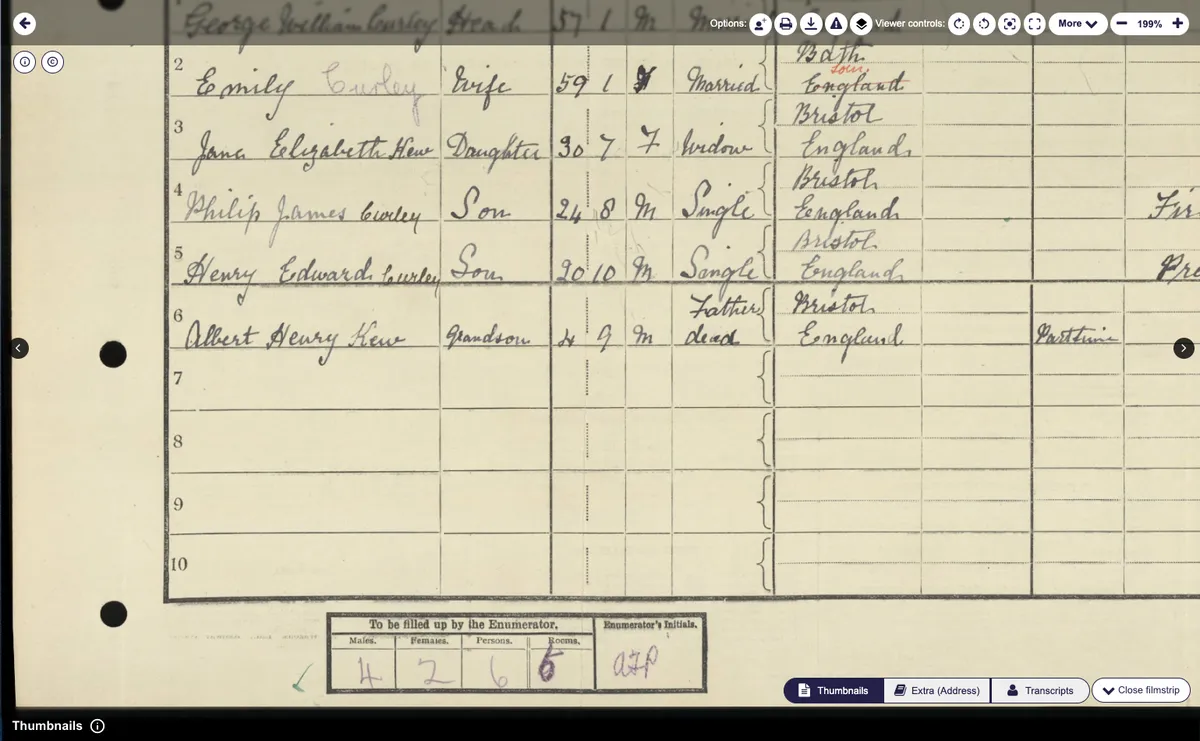

4. View the image

The image includes a note by the enumerator of the number of people in the house by sex and the total number of rooms.

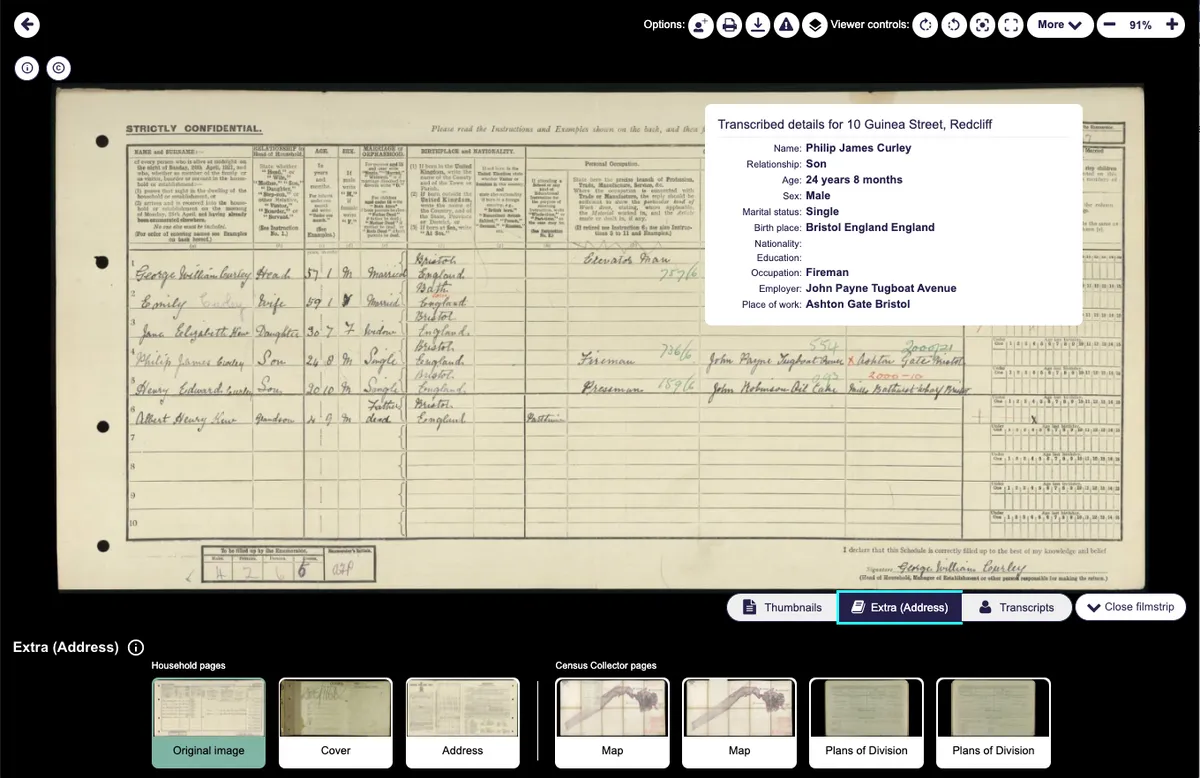

5. Hover to see a transcript

Hover the cursor over an entry to view a transcript. Click ‘Extra (Address)’ for the front page; address; Plans of Division; and maps.

6. View the address and more

As well as ‘Address’ other options include ‘Cover’ with details of the enumeration district as well as maps and plans of boundaries.

Where were our ancestors living in 1921?

In 1921 most people in England and Wales lived in a terraced house. The majority rented a house, or rooms, and new property tended to be sold to private landlords. The Lloyd George Domesday Survey held by The National Archives at Kew (currently being digitised and indexed by TheGenealogist) and rate books (held by county record offices, and on Findmypast) provide useful information that distinguishes owners from tenants. The middle classes paid rent annually or quarterly and the working classes paid it weekly; for most it was the biggest fixed expense in the household budget.

Overcrowded slum dwellings that were damp, insanitary and infested with vermin affected the health of their occupants, and meant that many men were not fit to be conscripted into the military. In the First World War rents soared, and there were growing evictions. When the men returned from war there was a real fear of working-class revolt against slum conditions.

A call for “homes fit for heroes” resulted in an extensive municipal housebuilding campaign from 1919. About 1.1 million new houses had been built for rent by 1939, meaning that local authorities owned 10 per cent of Britain’s housing stock. Some people took things into their own hands, building makeshift homes out of former army huts and railway carriages in ‘plotlands’.

It is difficult to put an exact figure on how many houses were in owner-occupation in 1921, but it seems likely to comprise less than a quarter of homes. Artisans could become owner-occupiers in places where there were stable populations and good incomes as well as building clubs and societies, such as in South Wales and some northern towns.

Speculative builders erected about three million houses between the wars, most of them semi-detached in suburban locations. From 1932, aided by reduced building costs for smaller houses and the availability of mortgages, they were affordable by the new lower-middle classes who had moved up the social scale into white-collar occupations, and also by the better-paid working classes in new industries in the Midlands and the south-east of England.

An estimated 1.1 million privately rented houses were sold to owner-occupiers in the interwar years, mainly in the 1920s. Most were older terraced properties without modern amenities such as bathrooms, and many were in a state of disrepair. This brought them within the reach of families who could not afford a modern house, and tasteful conversions

of dilapidated country cottages duly became fashionable among the middle classes.

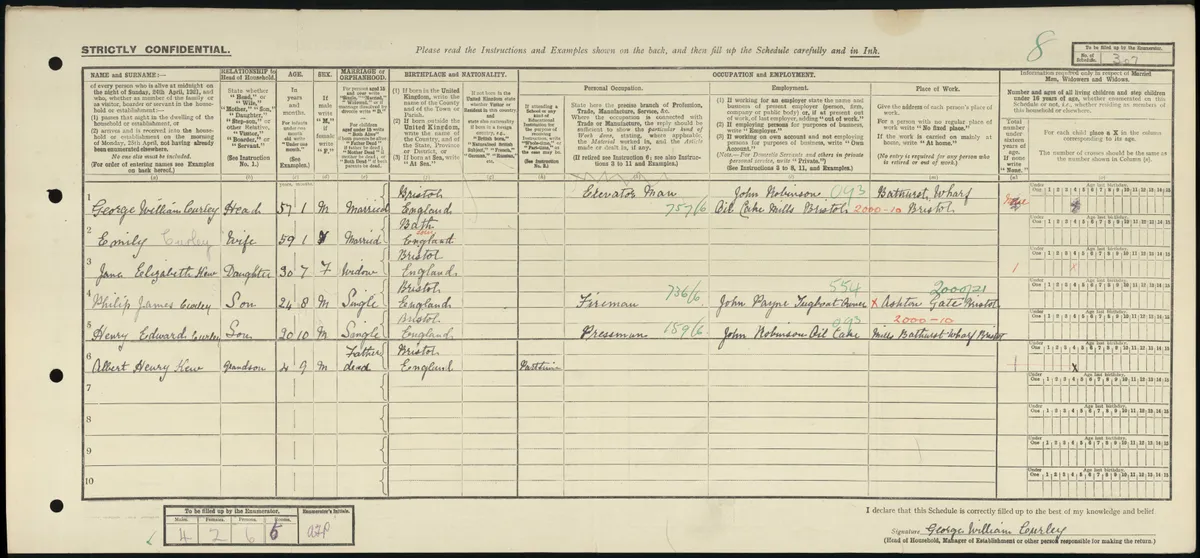

What does the 1921 census reveal about our ancestors’ houses and the ways they lived in them? The first thing to understand is that each household was entered separately, so you might find multiple schedules if the house was in multiple occupation. Living rooms, bedrooms and kitchens were enumerated, but landings, lobbies, closets, bathrooms and any warehouse, office or shop rooms were excluded. Sculleries were only counted if meals were eaten in them. In the image of the original record you will find a list of the total number of males, females and persons, and the number of rooms they inhabited. You should also note the ages of any children.

You might find multiple schedules if the house was in multiple occupation

It might have been difficult for separate households to maintain privacy within the same dwelling. Smaller houses often didn’t have an entrance hall, so in the typical ground-floor layout of two reception rooms inhabitants had to walk through one to get to the other. Even in larger middle-class houses it was not uncommon for two bedrooms in the rear return to be built without a corridor. Many clung on to the custom of a parlour for best, typically the front reception room.

In 1921, 10 Guinea Street has a total of 11 rooms occupied by 10 adults and four children. In contrast, 62 Falkner Street, Liverpool, the property we explored in the first series, has widow Fanny Snewing (64), her son Charles (42) working as a grocer’s assistant and daughter Lilian (27), both single, occupying 10 rooms. This gives a real indication of the family’s wealth, which you would not expect if you went by Charles’ occupation and is indicative of Fanny’s inherited fortune.

In larger middle-class houses, households were negotiating the impact of the ‘servant problem’. The press advocated on behalf of the ‘New Poor’ who were impacted by postwar inflation and struggled to maintain their prewar lifestyle. Good servants were harder to find because many young women who had been employed in domestic service before the war rejected the hard, lonely work of domestic service. They preferred the better pay, conditions and companionship they had experienced in wartime work, which translated now into factory, shop and clerical work.

Nevertheless, domestic service remained the biggest source of female employment. However, more servants lived out and you will see this reflected in the census where the place of employment is given as a different address to the one where they lived. The idea of the modern, professional housewife running her labour-saving home with reduced paid domestic help or none at all emerged. Consequently, the kitchen was relocated from the basement to the ground floor. This is one reason why the number of rooms in a dwelling may differ between 1911 and 1921.

The interiors of most houses in 1921 looked much the same as they had done before the war or earlier. Dark-coloured paint hid the dirt of coal fires and the street. Furniture was expected to last a lifetime after marriage, making timeless antique styles popular. Nods to fashion were more likely to be made with wallpaper and textiles. The spread of electrical appliances beyond irons and curling tongs was limited because in the late 1930s there were still numerous AC and DC systems in use, even in the same towns. If the household could afford a luxury, it was more likely to be a gramophone or a radiogram to enhance leisure.

Finding elusive ancestors

It is, of course, easier to find an address in the 1921 census if you know the one you are looking for, but even then there may be challenges. There could be transcription errors, in which case a wildcard search might yield results. Houses may have numbers where they previously had names, or they may not have numbers or even street names at all especially in rural locations. Online collections of old maps may help. Ideas of who may be resident can be gleaned from an address search in the 1911 census and the 1939 Register.

Sometimes you may have no choice other than to search through adjacent addresses. In this case, a trip to one of the three hubs where you can search the 1921 census for free may prove economical.

If you are looking for a house your ancestors lived in then electoral registers, telephone directories, birth and marriage certificates, and First World War service records can all provide addresses. If you are struggling to find the property using the standard address search, try using the optional keyword search on Findmypast’s ‘Advanced search’ screen. It includes the entire database, every single field, except for the numbers – so if there is anything missed in transcription, the optional keyword search should pick it up.

The enumerator books and summary books we see in other censuses were unfortunately discarded and destroyed – instead, we have the Plans of Division, which showed how each enumerator division was divided and the journeys taken through them. The descriptions in the Plans of Division pages offer the estimated number of families, a description of the boundary of the district and the contents of the district. They can be especially beneficial in metropolitan areas. Read through the description to find tenements and other types of housing. You will also find maps and a cover sheet.

The British Newspaper Archive is invaluable when researching A House Through Time; the collection is also available to ‘Pro’ subscribers to Findmypast. An address search, limited to the years in which you are interested, can reveal adverts for rooms to let or domestic servants, auctions of contents, and news stories about the house and its residents. For a broader timespan sale listings can reveal details about the house such as the number of rooms and their layout. Google Street View, old postcards (TuckDB Postcards has a huge searchable database), gazetteers, atlases and directories will give you a wider context for the area including local schools, hospitals and businesses.

10 Guinea Street: The Bristol property from series 3 of A House Through Time at the time of the 1921 census

The 1921 census contains four separate entries for households at 10 Guinea Street. An auction record dating from the 1880s reveals how the house was adapted for multiple occupancy. The basement floor has a cellar and a WC; the ground floor features two sitting rooms, a china pantry, a kitchen and a bedroom; two sitting rooms, a pantry and a bedroom are on the first floor; and the top floor is home to two attic bedrooms. There is also a garden with a small three-roomed cottage in which more tenants can be housed.

All four households are members of the Curley family, headed by George William Curley (57), an elevator man at John Robinson, which Grace’s Guide describes as “Crushers, refiners and manufacturers of linseed, cottonseed, rapeseed and other oils; manufacturers of linseed, cottonseed and feed cake”. George and his wife Emily were resident in the house in the 1911 census along with two of their adult daughters, one of their sons and his wife and a boarder, making a household totalling seven adults and two children living in eight rooms. However, in 1921 there are a total of 11 rooms, perhaps because the cottage is now recorded as part of the same address.

In 1921 George and his wife Emily (59) are living as one household along with their single sons Philip James Curley (24), a fireman at John Payne (shipbuilders and marine engineers), and Henry Edward Curley (20), a pressman at John Robinson. They have taken in their daughter Jane Elizabeth Kew (30), whose husband was killed in the war only two years after they married, and her son Albert Henry Kew. This makes a total of five adults and one child living in six rooms. Their daughter-in-law Lily (35) is listed in a separate household of two rooms with her daughter Dorothy (7), whose father (presumably George who was present in the house in 1911 but absent now) is listed as alive. This makes eight rooms in total, which matches the number in the main house.

The other members of the extended Curley family may be living in the three-roomed cottage. Another household is formed by William Alfred Curley (38), assistant electrician for the Imperial Tobacco Co, his wife Minnie Menthol (37) and their daughter Gwendoline (12), who live in two rooms. The final household who are living on only one room comprises the Curlings’ daughter Rosina (29), who lost her first husband in the war, with her second husband James Barling (23), a fireman working at John Robinson, and William Batten (4), her son from her first marriage.

Deborah Sugg Ryan is professor of design history at the University of Portsmouth and author of Ideal Homes