What were the London Docklands?

It’s hard to believe today but 50 years ago, the whole of East London along the river was dominated by the London Docklands – a sprawling network of quays, ancient wharves, deep canals and high-walled docks that stretched along the Thames from the City to Tilbury. The port provided employment for over 100,000 men and generations found employment at the waterside. Work was physically demanding but plentiful and dockworkers’ pay, while not a king’s ransom, was sufficient to raise a family and keep a bit back for beer money. Dockers and their families naturally assumed that the port would always be an integral part of London. Little did they know that in their lifetime, almost all traces of it would be swept away as massive changes in shipping made the London Docklands redundant.

When were the London Docklands founded?

The Romans founded the first harbour in London close to where London Bridge stands today and over the next millennium, the port gradually expanded eastwards to accommodate the increasingly large vessels that plied their trade in the city. The small quays evolved into huge, enclosed docks, the first of which was the West India Docks, built on the northern tip of the Isle of Dogs in 1799. The complex provided a template for all future enclosed docks in the city, comprising massive basins in which ships could anchor, accessed via gigantic locks leading from the river. These were surrounded by enormous warehouses where goods could be safely stored, protected by towering walls running the entire length of the site’s perimeter.

The West India Docks were an instant success, which prompted further developments throughout the 19th century. First came the London Docks in the ancient seafaring district of Wapping, then the East India Docks at Blackwall, the Surrey and Commercial Docks across the river at Rotherhithe and the St Katharine Docks next to the Tower of London. Later in the century, vast new steam ships plying their trade at the port prompted speculative developers to create even larger basins further east, where they were more accessible to the huge vessels. The Port of London acquired the Victoria and Royal Albert Docks on the Plaistow Marshes, the Millwall Docks on the Isle of Dogs and the Tilbury Docks on the Thames estuary in Kent. These colossal waterside developments were complemented by (and were in direct competition with) numerous wharves that lined both sides of the river from London Bridge to Silvertown, occupying a staggering 3,000 acres of land.

What was life like in the London Docklands?

The London Docklands provided major employment in the riverside districts of South and East London, and the majority of dockers lived close to their place of work, as their wages were not sufficient to cover travelling expenses. By the late 19th century, the oldest part of the port around Wapping and Limehouse was a densely packed, rag-tag mixture of ancient rookeries and common lodging houses, interspersed with new, ‘model dwellings’ inhabited by families fortunate enough to have a steady income. The dockers shared their surroundings with impoverished Eastern European Jews, who had fled their homelands during the terrifying pogroms of the 1870s, and a constantly changing succession of sailors who were good customers for the numerous pubs and brothels in the area. A little further east, the back rooms of grocery shops along the Limehouse Causeway harboured smoke-filled opium dens that catered for Chinese sailors searching for an evening’s entertainment. To the south east of Limehouse lay the Isle of Dogs, the location of Cubitt Town – an estate created almost exclusively for workers at the Port of London. Cubitt Town was the brainchild of speculative developer William Cubitt who developed the estate on a bleak strip of Thames-side land in the 1850s. From the outset, his risky venture paid off as the small terraces filled with workers from the nearby West India Docks and later the neighbouring Millwall Docks.

Over the river at the Surrey Commercial Docks, the area retained a distinctly maritime atmosphere where tall ships moored in the dock basins could be glimpsed in between the uniform terraces of red brick houses. Further east, the Royal Docks were sandwiched in between Silvertown – an unpretentious housing estate built in 1852 by Samuel Winkworth Silver for workers at his nearby rubber factory – and Canning Town, which lay just north of the Victoria Dock’s massive rectangular basin.

What work did London dock workers do, and how much were they paid?

The London Docklands offered a wide range of jobs for the men who lived in the neighbouring districts. Once a ship had docked and its cargo had been assessed by customs, it was loaded onto barges and lighters that had been queuing up outside the dock since the ship’s arrival. The lighters were hardworking little craft that had been a constant presence on the river for hundreds of years. Their work was so essential to the port that, in the late 18th century, the government granted them the right to collect goods from any enclosed docks without having to pay a fee to the owners. This privilege, known as the ‘free water clause’, was worth its weight in gold in later years, when a slump in trade made work scarce.

Ships’ cargoes were stored in tall warehouses that surrounded the dock basins. These structures were up to five storeys high and were designed to accommodate a great weight of merchandise. Some incorporated showrooms that were rented by merchants to display their goods. The St Katharine Docks specialised in warehousing luxury items including ostrich feathers, ivory and perfume, for which there was an on-site workshop where scent was extracted from the raw materials. The valuable nature of many warehoused goods proved too tempting for some dockers. Stealing from crates was particularly popular as it was quite easy to remove a slat, take out some of the contents and then replace the stolen goods with something worthless of a similar weight. The slat was then replaced with such expertise that the theft often remained undetected until the cargo reached its final destination.

Luxury goods were not the only cargoes brought into the Victorian Port of London. During the 19th century, demand for building materials was so great that the Surrey Commercial Docks specialised in receiving timber shipments. The cumbersome cargoes required expert handling by men known as ‘rafters’ as the wood could split if it was allowed to dry out. They sorted the untreated timber by length, quality and customer, and then floated it to storage ponds ready for collection. The rafters learned their trade through a seven-year apprenticeship and their pay depended on the size of ship they unloaded. During the 1860s, ‘short hour’ ships, which could be emptied in under eight hours, offered pay of 4 shillings per day; ‘long hour’ ships, which took up to 12 hours to unload, offered an extra shilling per day. The busy season lasted from July to October and during this time, the rafters were employed virtually every day. However, during the quieter months, they often had to take on other jobs to make ends meet, as did many other dock workers.

Once a ship’s cargo had been deposited at the quayside, porters took on its removal to the nearby warehouses. Their job was skilled, exhausting and could be dangerous. In the 1850s, a deal (board) porter at the Commercial Docks told the writer Henry Mayhew, “ours is very dangerous work. We pile the deals sometimes 90 deals high… and we walk along planks with no hold, carrying the deals in our hands, and only our firm tread and our eye to depend upon… Last year there was, I believe, about 35 falls but no deaths. If it’s a bad accident the deal porters give 6d apiece on a Saturday night to help the man that’s had it.”

Due to the unpredictable nature of shipping, work at the London docks was notoriously inconsistent. In busy periods, the ‘perms’ (men on a permanent contract) were assisted by casual labourers, a vast and disparate group of men who for reasons of personal choice, domestic obligations, bad luck or pure indolence, could not find permanent work. The casual labourers were known as ‘pokers’, because they were always poking about looking for work. Many of them lived lives of relentless poverty from which there was little hope of escape. One sad soul interviewed in the early 1850s lamented, “I’ve never stole, but have been hard tempted. I’ve thought of drowning myself and of hanging myself; but somehow a penny or two came in to stop that. Perhaps I didn’t seriously intend it.”

Although work for many was scarce, one source of almost constant employment for the casual labourers and skilled dock workers alike was the unloading and storage of coal, which by the 19th century, had become one of the principal cargoes at the Port of London. In 1805, when the city was beginning to feel the effects of the Industrial Revolution, 1,350,000 tons of coal arrived at the docks. By 1848, that amount had risen to 3,418,340 tons, which was brought in throughout the year by 2,717 vessels, employing over 20,000 seamen. Once a coal ship had moored at one of the docks, a gang of ‘coalwhippers’ were requested by the captain to haul the cargo from the ship’s hold by means of pulleys. Their unusual name came from the sudden jerk with which the men whipped the cargo onto the deck.

Whether unloading timber, coal or any other commodities, the dock workers generally organised themselves into gangs of up to 13 men to complete the work. These gangs were usually comprised of individuals who had known each other for some time, as good working relationships were essential to ensure that the sometimes-dangerous work was completed without any mishaps caused by arguments or misunderstandings. The gangs were well known to the contractors at the docks, who would negotiate the price at which a ship would be unloaded and then arrange for the appropriate number of gangs to complete the work.

Remuneration for dock work varied wildly depending on the worker’s status. By the 1880s, permanent employees, such as warehouse staff, could earn between 20 and 30 shillings per week. Stevedores – skilled men who loaded the ships – could also command a reasonable wage. However the casual labourers were only paid an average of 5d per hour and work was by no means guaranteed.

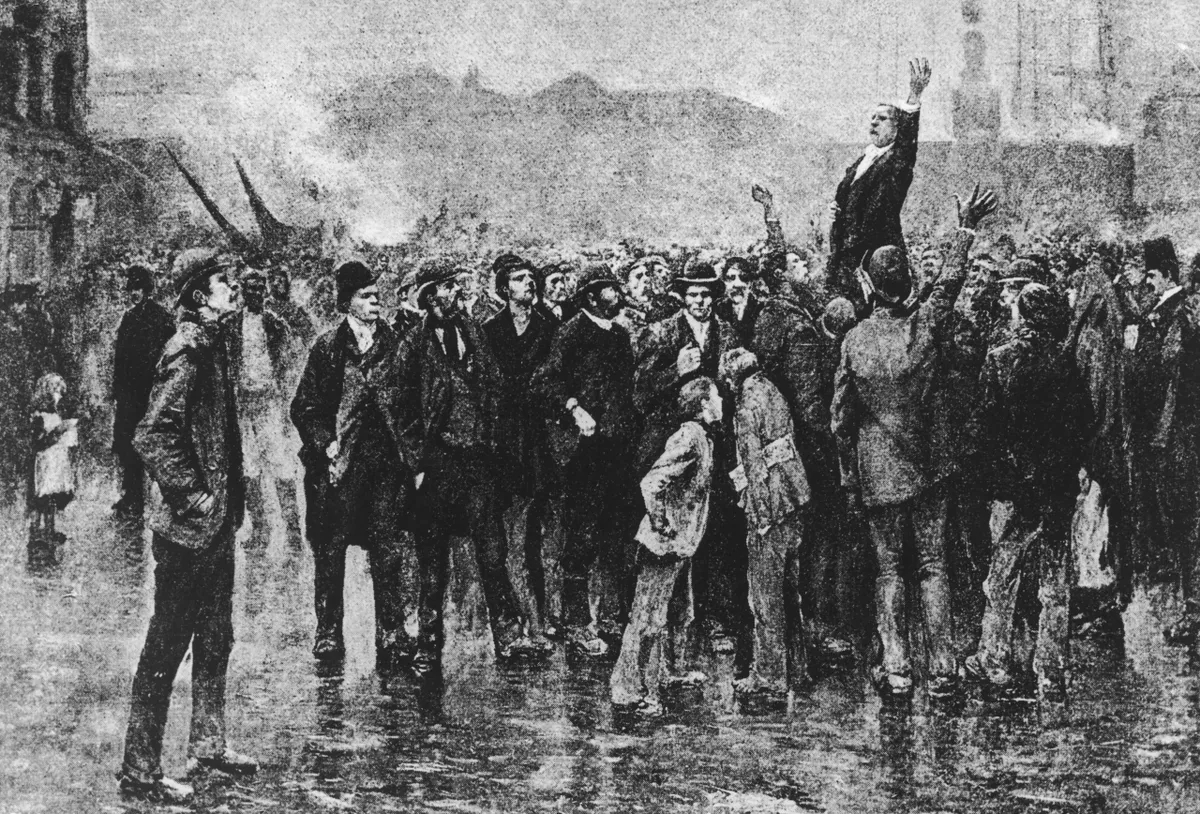

The unpredictable, hard and ultimately uninspiring nature of the dockers’ work meant that cheap and temporary escape from their mundane lives was essential to many. As a group, the dockers had a reputation for enjoying a drink which, until an Act of Parliament was passed to stop the practise in 1843, was exacerbated by the fact that many were habitually paid in public houses. As a result, many London dock workers suffered from alcohol-related illnesses, including cirrhosis of the liver and delirium tremens. The parliamentary Act that ended the publicans’ lucrative recruitment drives partially solved the problem of widespread drunkenness among the dockers. However, it unknowingly caused another as the men looking for work were now forced onto streets surrounding the docks when seeking employment. From dawn, the areas outside the docks’ gates would throng with casual labourers waiting to be selected at what was colloquially referred to as the ‘call-on’. As an unprecedented amount of poverty-stricken families flooded into the East End looking for work in the latter part of the 19th century, the way casual labour was employed at the docks proved to be a catalyst for the improvement of employment rights and empowered the embryonic Trades Union movement, leading to the 1889 London dock workers’ strike.

Why did the London Docklands decline?

As the 20th century dawned, the dock companies found themselves at perpetual loggerheads with the increasingly powerful and militant unions. The problem was exacerbated by the fact that as ships increased in size, the ancient Port of London was gradually becoming inaccessible. In addition to this, competitive rents for warehouses offered by the independent Thames wharves meant that many of the enclosed docks faced bankruptcy if the situation was not improved. In a dramatic move, the government resolved to nationalise all of London’s enclosed docks; and in 1909, overall control of these gigantic structures was given to the newly formed Port of London Authority. This drastic measure initially paid off and despite the disruption of two World Wars, by the 1950s, the London Docklands had entered their last boom period.

The final demise of the London Docklands was not brought about by trade unions or competition from wharves, but the arrival of container ships. It became impossible for the Port of London (with the exception of Tilbury) to accommodate these huge vessels, as the Thames was simply too shallow for them to safely navigate. Ship owners spurned the historic port in favour of the great sea ports and the docks gradually closed. One by one, these hives of industry shut down, leaving desolation in their wake. Families who had earned a living at the waterside for generations moved out to the new towns of the home counties in search of alternative employment. By the mid-1980s, the docks were a wasteland and any visitor to the deserted streets would have been hard-pressed to imagine how they were once filled with colour and life. Towards the end of the 20th century, the London Docklands Development Corporation redeveloped much of London’s quayside, particularly at Canary Wharf and Surrey Quays, but many of the vast basins that were once the most essential part of the docks still stand redundant.