The First World War was a transformative experience for millions of women. While thousands were widowed and thousands more left to care for an injured son or husband, about one million women found themselves directly engaged in war work.

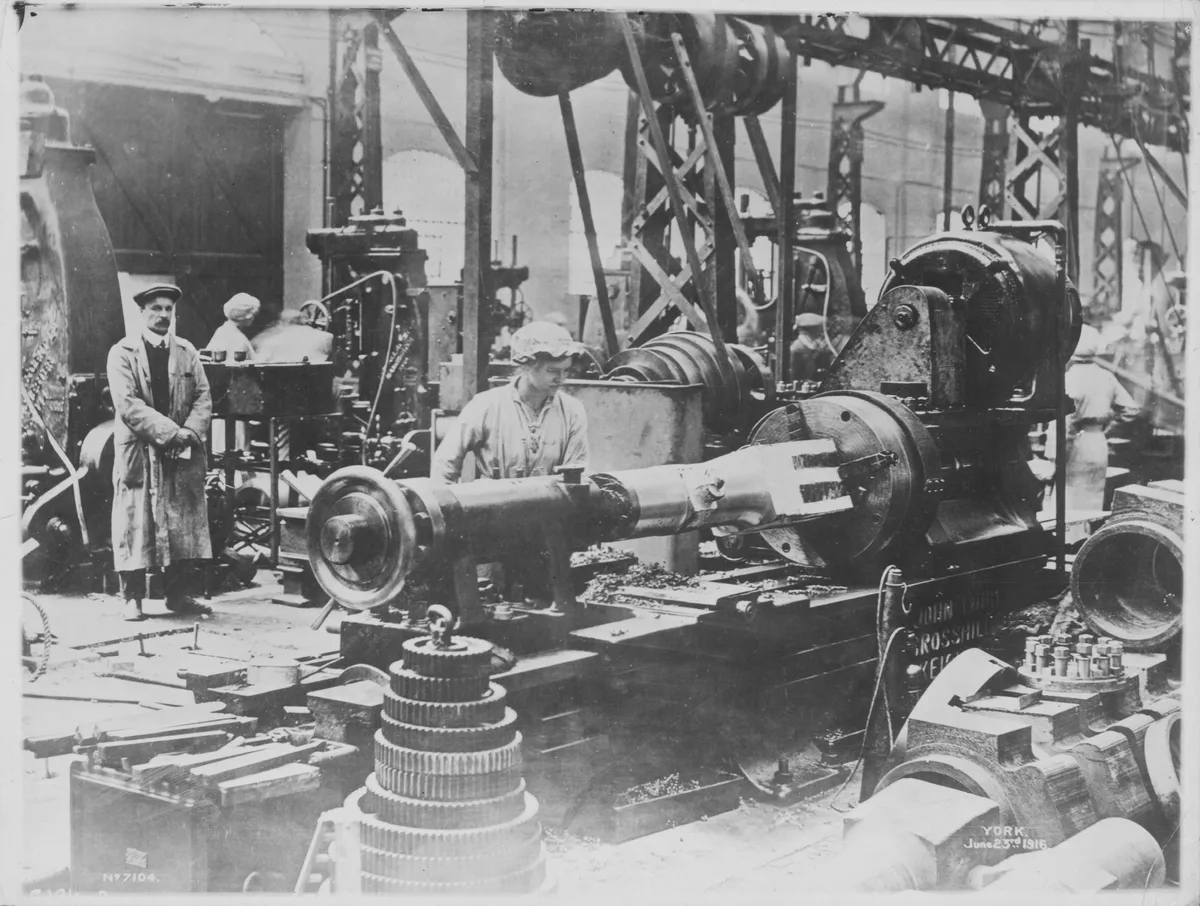

Amongst them were the munitionettes, the women who worked in munitions factories. 'Canary Girls' and 'Tommy’s Sisters', as they were sometimes called, were the lifeblood behind Britain’s biggest armaments effort ever.

Discover more about women who served in the First World War with our guide to First World War nurses

The recruitment of munitionettes began in earnest in 1915. By then, an increasing number of male munition workers were being recruited as soldiers. Over-optimistic forecasts of a short war were fading fast and it was becoming clear that this was a war which would be won, not with rifles and bayonets, but heavy artillery.

“Bombed last night, and bombed the night before; going to get bombed tonight if we never get bombed anymore,” ran one trench song as casualties soared and the shells, which eventually accounted for almost 60 per cent of the war dead, were filled, fused and inspected by a growing army of women.

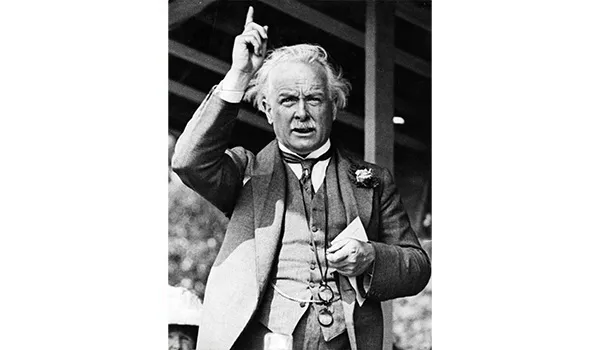

The munitionettes were signed up at local labour exchanges on the orders of the minister of munitions and future Prime Minister David Lloyd George. He had replaced Lord Kitchener, the moustachioed face on the ‘Your Country Needs You’ posters, who had stepped aside after a Daily Mail exposé, the Great Shell Scandal, that revealed serious shortfalls in the supply and quality of the British shells.

Lloyd George responded by turning on a bumbling, male-dominated armaments industry and transforming it into a relatively streamlined, Government-owned manufacturer powered by women.

Lloyd George had already allied himself to the suffragette cause, supporting a march through London in July 1915 as women bore aloft banners demanding the right to serve: “Mobilise Brains and Energy of Women” read one.

He also tackled the traditional opposition to female labour, which was at its most entrenched among the Clyde shipbuilders whose union was rigidly opposed to dilution. This was the training of unskilled or semi-skilled workers, mostly women, to do jobs normally done by their members.

By late 1915, the recruitment of thousands of munitionettes was underway. They were sent to work at the newly-expanded Woolwich Arsenal in London, and at Lloyd George’s new National Shell, National Projectile (for heavier munitions) and National Filling factories. The filling factories where munitionettes worked included Woolwich, Barnbow in Leeds, Aintree in Liverpool, Hereford, Quedgeley in Gloucestershire and Chilwell near Nottingham. Further factories were located in Hayes in Middlesex, Banbury in Oxfordshire, Whitemore Park in Coventry, White Lund (later destroyed by an explosion) at Morecambe and Cardonald and Georgetown near Glasgow.

The Glasgow factories alone soon employed about 40,000 munitionettes, 17-year-old Margaret Taylor among them. A Greenock woollen mill knitter, she lied about her age and joined up: “Some of the girls were wild: they belonged to the Red Skins gang, one of the most notorious in Bridgeton. But there was a tremendous sense of companionship,” she recalled in an interview with the Glasgow Herald in 1984.

Women were supposed to be 18 or over before they could do the most dangerous jobs and handle the explosive powder. East Ender Caroline ‘Queenie’ Webb described the work during an interview now held in the Imperial War Museum archives.

A former Bermondsey shirt-maker, Queenie prepared aerial torpedoes at the Slade Green Filling Factory out on the remote Crayford Marshes where she worked 12-hour shifts for 13 days in a row followed by 13 nights. That earned her a single day’s leave – “I used to sleep on me day off.”

Who were the Canary Girls?

Munitionettes who manufactured trinitrotoluene (TNT) shells were called ‘Canary Girls’ because the toxic TNT turned their hair and skin yellow. At the shift’s end, the Canary Girls returned exhausted to London Bridge Station aboard special munitioneer trains. “We would come off these… trains all yellow. Our hair was like ginger and our faces was bright yellow.”

Canary Girl Annie Slade, a 17-year-old from the Welsh Valleys, suffered from “working on the powder.” Interviewed for a Heritage Lottery project in 2001 she recalled being sent to Hereford’s National Filling Factory Number 14 and, after being issued with her uniform (white for the girls working on the lyddite, dark for those on amatol) and rulebook, was sent into the amatol and stemming room section.

Here she learned how to fill empty shells with the explosive, pouring the soapflake-like shards of amatol through a funnel into the mouth of rows of upturned shells. Every two hours, she changed places with the girl who worked the stemmer, a wooden pole like a shortened broom handle, which was set in the shell and tapped with a wooden mallet to pack down the explosive.

After a fortnight on days, Annie Slade transferred to the night shift to work “on the powder” where, it was rumoured, girls sometime fainted, turned yellow, missed their periods and even became infertile. One persistent rumour maintained that blondes were turned into permanent brunettes by the work. “I lost my teeth,” she recalled.

Nevertheless, one Hereford newspaper described Filling Factory Number 14, without giving away its location, as a place “where the motto is Sound Work” and the treatment was of “the best: [a factory] where breakfast is to be had for free and a half-hour dinner for 8d is the reward for an eight-and-a-half hour shift and where there is a lady supervisor and a lady doctor on hand and where a Welfare Committee takes seriously its duties to provide billets, provision of hostels and clubs.”

The correspondent conceded that there were dangers associated with the work, but assured readers “they have been so minimised that they amount to not more than that of railway travel.” This would prove to be a hollow promise.

The munitions factory at Chilwell in Nottingham was, like Hereford, involved in filling breech loading shells. (Each shell was marked on the base with the factory of origin: H stood for Hereford, CF for Chilwell). Chilwell would witness one of most devastating explosions ever experienced on British soil.

Nottinghamshire historian and the author of The Canary Girls of Chilwell, Maureen Rushton, takes up the story: “On Monday July 1, 1918 at 7.10pm there was a series of almighty blasts. Nearly eight tons of explosive had lifted itself skywards. A total of 134 people were killed instantly, 25 of them women. Only 32 people could be positively identified after the explosion, which also injured 250.”

The cause of the blast was never explained. Viscount Chetwynd, the factory owner, blamed human error and the official investigation accepted this vague explanation while conceding the possibility of sabotage “or the action of a disaffected worker”. Even as body parts were being collected into coffins – the dead were buried in a communal grave – efforts to resume operations were underway. Two months later Chilwell broke its own record for shell filling. There was talk in Parliament of presenting the entire factory with a Victoria Cross.

A news blackout and continued post-war secrecy has left most people unaware of the dangers facing the Canary Girls and their companions. However, one young woman did write eloquently about her experiences. Mabel Lethbridge’s biography, Fortune Grass, was published in 1934. Seventeen years earlier she was working at Hayes when the supervisor asked for volunteers to operate a machine that had already injured several others. As she filled the last shell of the day there was an explosion. “In the glare I saw girls rise and fall shrieking with terror, their clothing alight, blood pouring from their wounds,” she said. “’God help me’, I cried, sinking down among the flames.” When she came round in hospital doctors had amputated her leg.

Mabel received a small pension, but it was withdrawn when she secured secretarial work. Later in desperation she took to busking on the streets of London. The intrepid Mabel went on to set up in business and eventually, she claimed, became the first woman to run an estate agency in Chelsea.

Despite the work of women such as Mabel Lethbridge there were constant complaints about the conduct of the munitionettes. The author of one letter to a Hereford newspaper wrote of “sad tales of obscene language and immorality, all seen at late hours, after dances [at the factory]. Ask the doctors: They say the girls wear themselves out by work in the day and strenuous dancing every night, and are no longer fit for the exceedingly important work they are engaged in.”

A munitions worker wrote back: “Might I ask of our correspondents if any of them have ever attended any of the factory dances?” She continued: “After such strenuous work is it surprising that girls seek diversion of a lighter and brighter kind? The soothing rhythm of a waltz… helps them to retire to bed cheerful and happy.”

Most of the girls ignored the jibes and carried on with the job in hand. As one of the Woolwich work songs went:

"Way down in Shell Shop 2

You’ll never find us blue

We’ve worked night and day

To keep the Hun away."

Bill Laws is an author and editor of numerous titles on gardening and history. His latest book is A Ramble Through the History of Walking, 2025