When did rationing start?

The Second World War didn’t come as a surprise to Britain, and neither did the danger our hungry little island would be in. We were importing an estimated 55 million tonnes of food – 70 per cent of the total consumed – from overseas every year, and these ships would obviously make tempting targets for German submarines.

With the outbreak of war on 3 September 1939, the Government immediately assumed direct control of the nation’s imports of food and raw materials. A price freeze was also introduced, along with the rationing of petrol.

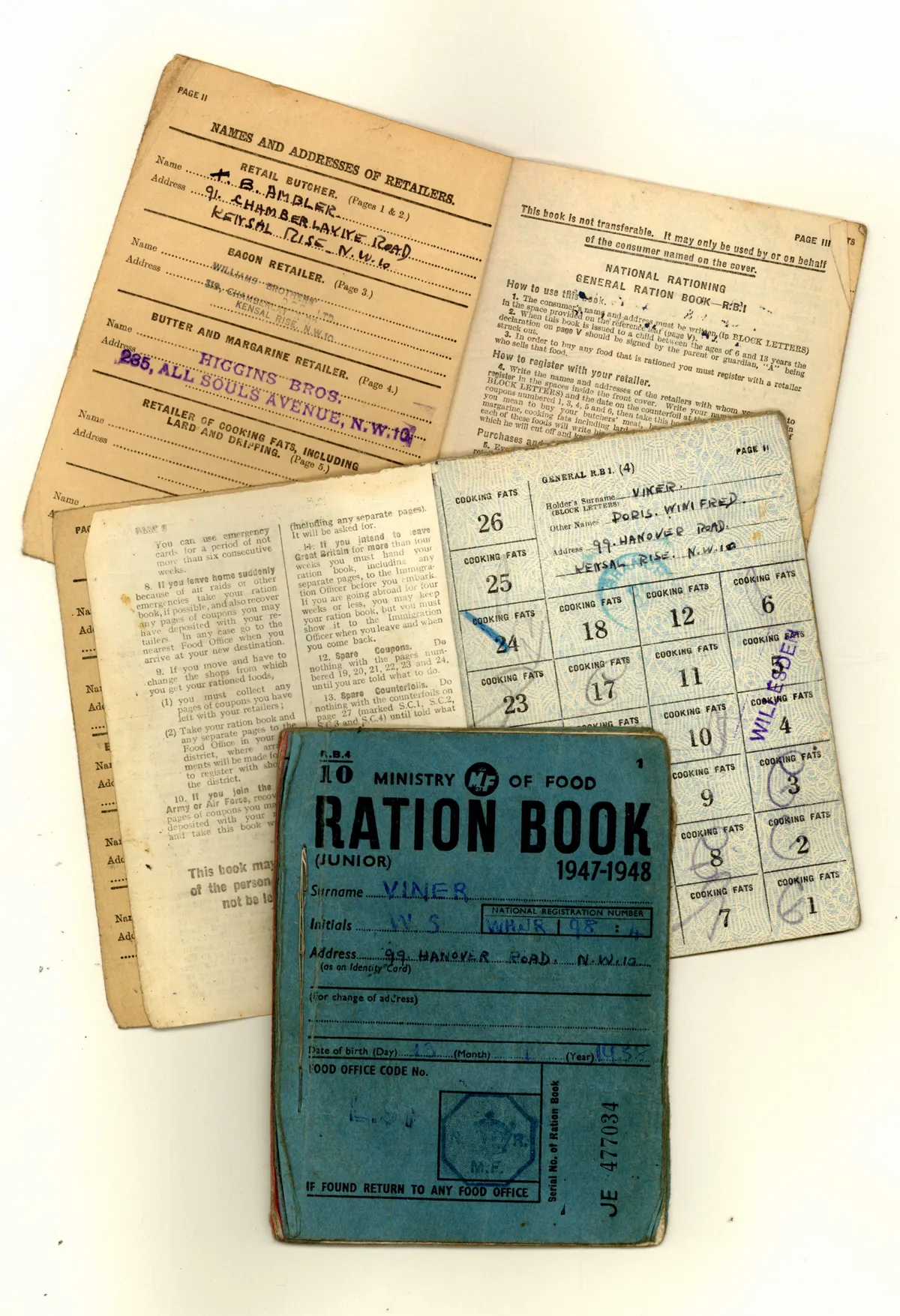

On 8 January 1940 rationing was introduced on butter, bacon and ham, and sugar, and by 11 March this was expanded to all meat. Everyone in the UK was issued a ration book in their name by the Ministry of Food. Neatly pocket-sized, the ration book’s pages were divided into tokens that could be cut out (or scribbled on) as you paid for your groceries. Each household had to register with a particular butcher, grocer and milkman, to ensure – at least in theory – a perfect match between customer and stock.

In the first half of 1941, rationing was extended to eggs and cheese, and by February 1942 tinned and dried foods. Non-foodstuffs were added to the rationed list in 1941 too. Due to the need for uniforms, from 1 June clothing was rationed. Coal was rationed the following month, and by February 1942 soap was rationed so that the oils and fats used in its manufacture could go towards food instead.

What was rationing?

The typical weekly ration consisted of an egg, an ounce of cheese, two ounces each of tea and butter, four ounces each of bacon and margarine, and eight ounces of sugar.

Many of the oral histories held by the British Library provide insights into our wartime relations’ experiences. For example, May Chirnside – who worked in her family bakery in North Shields – recalled some people making Christmas cakes with liquid paraffin “because they didn’t have the fat”.

Rationing was as much an act of social intervention as it was a wartime necessity, levelling the classes – the Royal Family received ration books – and ensuring that even the poorest and most vulnerable had access to nourishing food. The Ministry of Food consulted with nutritionists to define the healthy diet for the first time. This included Scotland’s John Boyd Orr, who would win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1949 “for his lifelong effort to conquer hunger and want, thereby helping to remove a major cause of military conflict and war”.

Most adults received light brown ration books. Pregnant women, nursing mothers and children under five received a green ration book which entitled them to a daily pint of milk, double the normal ration of eggs, and first pick of fruit, and children aged between five and 16 received a blue ration book which entitled them to half a pint of milk every day and no limits of fruit. Cod-liver oil and fruit juice was also distributed free of charge to keep infants topped up with vitamins.

Essential foodstuffs – bread, flour, milk and eggs – were subsidised, with the Government paying hundreds of millions of pounds each year to maintain their prices at prewar levels.

Over the course of the war, the Ministry of Food fought its own campaign to win the public over. Swaggering seasonal veg like ‘Doctor Carrot’ and ‘Potato Pete’ strutted across posters, regular ‘Food Facts’ newspaper ads and Food Flash short films shared nutritional nuggets and ration-friendly recipes, while the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign, launched by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries in October 1939, encouraged people to turn their gardens into vegetable plots.

The 1942 Wartime Social Survey found that nearly two years into rationing, support was still high but the strain was showing. Around half of the respondents didn’t feel as though they had enough food to stay fit, 63 per cent opposed making rationing stricter, and a number of existing initiatives were met with grumbles.

Chief among their complaints was the ‘National Loaf’. Although bread escaped rationing, white bread became scarce and in 1942 disappeared entirely to be replaced by a nutritious wholemeal National Loaf. Described as “terrible, dreadful, [and] unappetizing” by some respondents, its unappealing grey mushy texture was a result of using less sugar which causes the yeast to rise. So it’s no wonder that the loaf had an approval rating of only 52 per cent.

Despite the Ministry of Food’s best intentions, inequalities persisted. Since tinned goods were initially exempt from rationing, wealthier households were able to stockpile at the expense of poorer ones. In addition rationing and price caps were only imposed on restaurants in January 1942, meaning that those who could afford it were still able to eat more than their share.

Country folk had an advantage too, as game and fish weren’t rationed. Milk, eggs and cheese were also more plentiful in the sticks. In another British Library oral history, Joan Brown recalled her rural grandparents sending care packages to her home in Worcester: “Grampy used to go and shoot pigeons, rabbits, and many a time send a letter to dad and say, ‘We’ve put something on such or such a train,’ and dad would go and pick it up. We’d [also] get apples, plums. We’d do a lot of bottling of the fruit. We never had to want.”

The letter of the law wasn’t always adhered to – many people saw nothing wrong with gifting clothing coupons as a birthday present, or selling eggs from their own chickens. That didn’t necessarily make one a profiteer, but punishments varied from a £500 fine (£18,000 today) to a maximum five-year sentence.

When did rationing end?

Although the war ended in 1945, rationing endured for another decade with restrictions on meat only being lifted on 4 July 1954. Even bread was finally subject to rationing in 1946. Those little ration books were a feature of British life for 16 years, but the effects of rationing lasted much longer. Infant mortality decreased and birth weights grew as a result of innovations in infant nutrition that today still inform policies around school meals, access to fresh fruit and vegetables, and milk for the under fives.