Known today as an international church and charitable organisation, the Salvation Army was community-minded from the outset.

The Salvation Army was founded in 1865 by Methodist preacher William Booth (1829-1912) in the East End of London, at a time when poverty, crime, disease and overcrowding in the area were causing widespread concern. Christian social reformers felt that low church attendance was part of the problem, and one of many missionary efforts to evangelise the local population saw Booth invited to conduct a week’s religious services in a tent in Whitechapel. Booth’s use of open-air preaching to attract passers-by into powerful indoor meetings proved so effective there that he decided to remain and develop his work into a permanent mission, the East London Christian Mission.

Booth’s tactic of taking Christianity out of the churches to the people did not stop at street preaching. The mission soon began holding services in theatres and music halls, cleverly attracting audiences with posters mimicking those of popular shows. Its first headquarters was a former beerhouse with an American bowling saloon which the mission converted into a meeting hall for 300 people. By 1867, this hall was crowded to the door every evening.

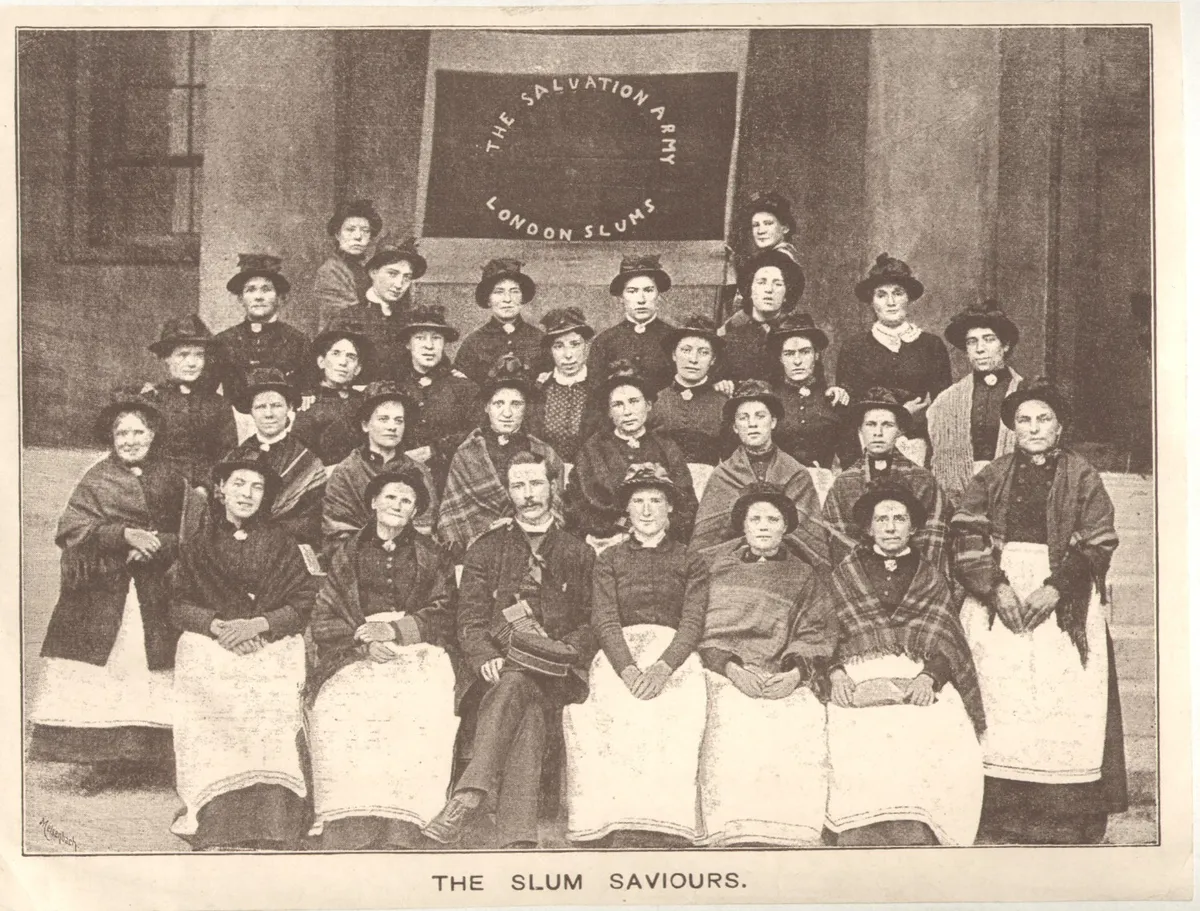

As people were converted, the mission trained them in public speaking so that they could spread the gospel within their own neighbourhoods. New converts learnt to give testimonies telling the story of their own path to salvation, in the hope of winning over others. The influence of William Booth’s wife Catherine (1829-1890) meant that women were equally encouraged to take up public work, and they did so in ever-increasing numbers. Conversion stories printed in the mission’s monthly magazine paint a vibrant picture of the working people they reached: “a drunken horse-dealer”, “the landlady of a public-house”, “a Dutch sailor”, “the Hallelujah inspector” and “a musician saved”.

Gathering followers and momentum, the mission expanded beyond the East End in the 1870s and dropped ‘East London’ from its name. British foreign policy had created an atmosphere of jingoism that started to influence the Christian Mission’s approach. In 1877, evangelist Elijah Cadman, the “converted sweep”, caused a stir by handing out bills announcing a war in Whitby and calling for recruits to his “Hallelujah Army”. He appointed himself its captain and, when William Booth visited, introduced him as the general. By the end of 1878, the Christian Mission had become the Salvation Army.

From then on, its full-time evangelists were called officers, and members were soldiers. Mission stations became corps. Prospective officers spent several months as cadets at a training garrison before their commission. Uniforms were adopted, and military-style brass bands became a feature of open-air ministry.

The life of an early officer was one of perpetual movement. Examples from the earliest surviving directory of officers’ appointments show just how relentless it was. Amelia Vernon gave up her work as a servant to become an officer in January 1881. By the end of 1883, Vernon had led corps in Alfreton, Blackburn, Exeter, Heckmondwike, Huddersfield, Kilham, Leamington, Lincoln, Long Eaton, Portsmouth, Shipley and Wallsend. Plasterer, mason and piccolo player Abraham Rickard became an officer in September 1882, and within 12 months had been stationed at Cwmbran, Hackney, Monmouth, Ross and Warminster.

Cadets travelled the country in ‘cavalry forts’: horse-drawn caravans that brought the Salvation Army to rural towns and villages. Pioneer parties of women took the army to the USA in 1880 and France in 1881, and it soon spread even further afield to India, Australia and beyond. Most who signed up were in their teens or twenties.

As popular as the Salvation Army’s lively public work proved with some, it also drew resistance. Taunts, jeers and sometimes stones were thrown by so-called ‘Skeleton Armies’ who opposed its stance against alcohol and gambling. Some local authorities objected to its boisterous street processions, and arrested the participants. The difficulties of these early years meant that many officers understandably stepped back from the work, but plenty carried on. Having transformed their own lives by joining the army, they were determined to give others the same opportunity.

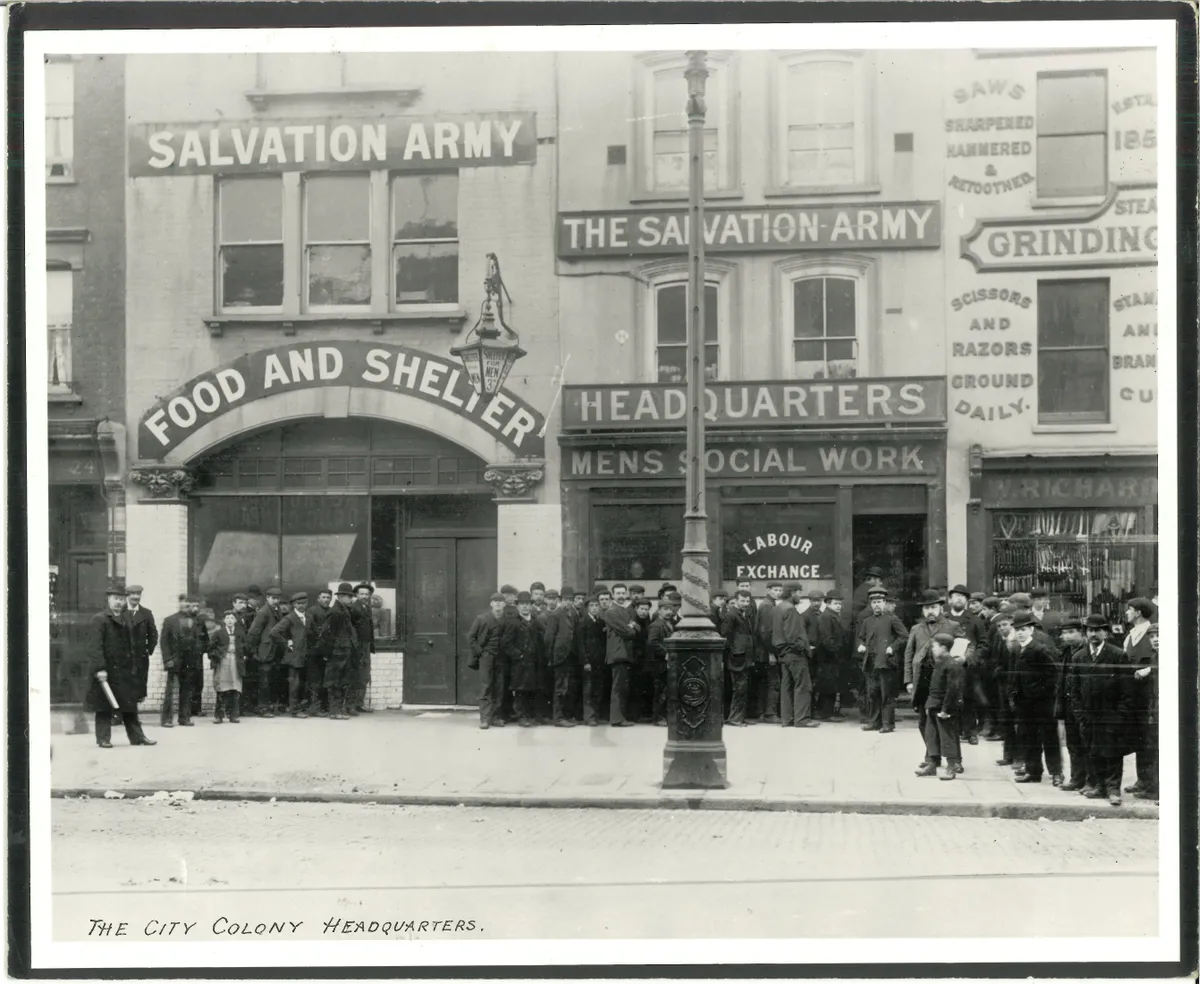

Their desire to help others practically as well as spiritually soon began to take the Salvation Army’s work in new directions. Female cadets formed a Cellar, Gutter and Garret Brigade whose members lived in slum districts assisting their neighbours with cleaning, nursing and childcare. ‘Midnight’ ministry to women working in prostitution led to the creation of refuges and maternity homes. Shelters and food depots began to be opened for people who were homeless or struggling to make ends meet, like striking London dock workers in 1889.

Salvation Army history: Key resources

Places

Salvation Army International Heritage Centre (IHC), London

The IHC holds the training and service records of most officers commissioned in the UK since the late 19th century, corps membership records, and records of people assisted in many of its institutions. The IHC also has a museum and a library with books, pamphlets, newspapers and magazines.

William Booth Birthplace Museum, Nottingham

Find out more about the early lives of William and Catherine Booth, and how the couple’s formative experiences shaped the Salvation Army.

Books

Pulling the Devil’s Kingdom Down by Pamela J Walker

Walker delves into the origins of the Salvation Army.

The Salvation Army by Susan Cohen

Cohen’s visually rich book is a concise and engaging overview of the history of the army.

With God on Their Side by James Gardner

Gardner explores the opposition that the early Salvation Army faced.

Ruth Macdonald is the archivist and deputy director at the Salvation Army International Heritage Centre