Between the years 1869 and 1939, 100,000 children were sent by Britain to Canada. Their story is not well known and yet it should be because these children were the ancestors of 11.5 per cent of the Canadian population today. Who they were and why they were sent are questions which take us back to the mid-19th century and the teeming streets of urban London.

Find out how to uncover more about members of your family who were child migrants here

At this time people were flocking to large industrialised cities such as London, Liverpool and Glasgow in search of work. Housing was in short supply and sanitation non-existent so that cholera, smallpox and other serious diseases were rife. Death was ever-present, making wives widows and children orphans with no means of support. Children born into poverty had very little to eat, no education, were sometimes abandoned by their parents and often exploited for their work.

The government’s answer to this situation was to put the poor into the workhouse, and to make the experience so unattractive that people would do anything rather than go there. However, this was no real choice and the destitute would end up living on the streets and often resorting to crime to subsist.

Several philanthropists, including Maria Rye, Annie Macpherson, William Quarrier, John Middlemore, Father Nugent, James Fegan and Dr Barnardo, were moved to help those in such dire straits, particularly the children. Most were evangelical Christians strongly motivated to save the poor from sin and bring them to God. They dedicated their lives to this purpose through experience of the horrific conditions in the slums of London.

Annie Macpherson’s charitable work in the East End brought her face-to-face with the corrosive effect of drink. She wrote: “While yet in their mother’s arms, gin is poured down their infant throats, and a little later as a natural consequence childish voices beg for coppers to be spent in drink. Alas! No uncommon sight is it to see little girls of ten years old reeling drunk along the streets.” However, she was galvanised into action after her discovery of “a group of palefaced little matchbox makers” hidden away in an attic who spent all their waking hours bending pieces of wood, sanding them and covering them with paper. The youngest children were only three years old but all of them had sacrificed their childhood to earn just three farthings for 12 dozen matchboxes. Annie wrote a booklet about their plight and many fellow evangelicals donated money for her “Home of Industry”, which she set up in a converted hospital in Spitalfields where children could live and work under better conditions.

The philanthropists, with the exception of Maria Rye, all started their own homes mainly in the East End of London, but also in Birmingham, Liverpool and Glasgow. However, it soon became quite obvious that there would never be enough room for all the children in need of care. In 1869, Maria Rye had taken girls from the workhouse and sent them to Canada, where they became domestic servants. She opened the door and other child-rescuers followed suit.

Their justification wasn’t simply a question of numbers. In London, poor children were at every turn exposed to the corruption of the slums – to drink, to crime, to neglect, to exploitation – and the philanthropists felt that to send them to Canada would cut them off from their bad associations and help them to forge new and better ones in a more pious country. For the Poor Law Guardians, it was also much cheaper to send children to work in Canada than to keep them in Britain at the rate-payer’s expense. Dr Barnardo wrote: “We in England with our 470 inhabitants to the square mile, were choking, elbowing, starving each other in the struggle for existence; the British colonies overseas were crying out for men to till their lands, with few ties to bind them to the mother country, and at an age when they were easily adaptable to almost any climatic extreme.” For the child-rescuers it seemed, literally, a God-given opportunity.

For the child-rescuers it seemed, literally, a God-given opportunity

Escaping the poverty trap

But what was it like for the children? A Canadian migrant from the Middlemore Homes in Birmingham looked back on his childhood: “I remember coming home from school one day in England to find the furniture in the backyard and the house locked up. They had not paid the rent. I ended up in the Middlemore Homes. I never saw my mother and father again... I was not asked if I wanted to go to Canada. There was no choice... One year they sent a bunch to Australia and the next year to Canada.”

The children had no influence over the decisions made about their lives – they were to do whatever they were told and like it. Of course they were subjected to propaganda about Canada which gave them unrealistic expectations that must have made coming to terms with their new lives in a foreign land even more difficult. Dr Barnardo was pleased to report that, “‘Please may I go to Canada?’ is the most popular sentence just now on the lips of our girls – it comes even from the tiny ones of four or five...” But Barnardo should have known better – what four-year-old has any real concept of living in another country?

Millie Sanderson, a teacher in Barnardo’s Canadian Home for girls, tried to inject a modicum of realism into the emigration picture. On a trip to England, she told the Barnardo girls “...of short summers and weary winters when the poetry of life seems either to be parched with heat or shrivelled by cold; and then I spoke to them of work... Good, hard work is the order of the day.” She also added a cautionary note for over- optimistic philanthropists: “Canadian sunshine is bright and Canadian air is pure, but I never yet have heard that they have power to renovate corrupt hearts or reform evil lives.”

The abrupt change from the city streets of London to isolated farms in rural Canada was difficult for all the children. The climate was harsh, the work extremely hard and there was no one around to care much how they fared. Some experienced terrible cruelty, others simply neglect, and the lucky ones found a happy home. Most suffered the stigma of being a “Home Child” (as child migrants to Canada were called), not even owning to such indignity when they grew up. One girl was haunted by a comment made when she was out with her mistress. “The man who was helping her (the mistress) asked, ‘Who is that you have standing there?’ And she said, ‘That’s just the girl from the Home.’ And he said, ‘They’re pretty poor trash, ain’t they?’ And she said, ‘Yes, they are.’”

From a 21st century viewpoint, one of the worst consequences of child emigration was to take children from their families. Children were separated from friends they had known in the Homes and from their relatives, especially their brothers and sisters. Most of them had gone to Canada with their parent’s permission (although this was not always the case) and were able to keep in touch through the Homes, but maintaining contact was problematic. However, the fortitude of these children shows through for most of them grew up to find jobs, establish families and forge a new life for themselves. Those that could not cope returned to Britain. A few were devastated by abuse and friendlessness and took their lives.

Leaving Liverpool

The children were taken by train to Liverpool where they left for Canada on the mail ships of the Allan Line. The first group of girls from the Church of England Waifs and Strays Society left for Quebec on 23 April 1885 in the charge of Reverend Bridger, who wrote: “At the station their little red hoods attracted considerable attention; and when it was discovered that they were bound for Canada, many of the passengers kindly evinced great interest in them, one clergyman taking the trouble to purchase dolls for those who were not provided with them.”

They were taken out by tender and boarded onto the ship where each of them had a medical examination and were returned to shore if they did not pass. The children were unprepared for the sea voyage and seasickness worsened their first experiences. A boy travelling in 1910 describes the accommodation aboard the Mongolian: “My cabin was in steerage... The cabin was over the works of the ship and the clank of the steering gear together with the whine of the propeller shaft, the smell of hot oil and steam, and no ventilation, drove me out. I spent my nights hidden in a corner on deck against a ventilator shaft for warmth.”

However, once they had become used to their surroundings, the children began to enjoy themselves. One girl in 1912 wrote: “We were happy on board with the other girls. We played games... The sailors and the captain were very good to us.” In general, the crew seemed to have really concerned themselves with the comfort of the children.

Destinations in Canada were Halifax, Quebec City, Montreal, and St John in New Brunswick. A 12-year-old boy described the bleakness of the latter: “We were... marched off into the customs building, which closely resembled a huge barn... The interior was no more comforting than the exterior... The lighting consisted of single light bulbs suspended in two rows from the ceiling which gave the whole atmosphere an eerie effect.” From their point of embarkation, the children journeyed by train – often for three days – before arriving tired, hungry and bewildered at the receiving Home.

Each emigration society had its own receiving Home. They were usually large comfortable houses with big grounds outside a town. The Waifs and Strays’ Gibbs Home was in Sherbrooke, Quebec: “It stands on the right bank of the St Francis river, on rising ground, with a fringe of trees between it and the river, its grounds being partially devoted to the cultivation of garden produce, and partly laid down in grass... The Home itself is square with a verandah on three sides.”

The children did not stay long at the Home as it was important that they were settled in their new places as soon as possible. Farmers had put in their applications for a Home Child backed up by recommendations from clergymen and other well-respected figures, and all that remained was for them to choose who they wanted.

Unfortunately this was a humiliating event for the children, as one Catholic girl describes: “We were called inside – 12 boys and 12 girls – and lined up on each side of the room. There were four people there. The woman who was later my adopted mother came over to the little fair girl beside me and said, ‘I like this one.’ My adopted father kept watching me. Every time I looked at him he was smiling at me. He said to my mother, ‘I like this little dark one,’ and patted my head. So my mother said, ‘Well, I guess that’s it.’ And that was all that was said.” The children were taken away to the farms and their new lives in Canada began.

Farmed out

There was a system of visiting the children to make sure that they were all right but the huge distances worked against this and the children were not seen very regularly. However, it worked up to a point and many children were moved to better homes when abuse was discovered. One young girl explained that the farmer, “Slapped my face until I had a blister which formed a scab, and they wouldn’t let me go to church because people would see it. I was so afraid of being beaten that I ran away. I was taken in by a kind lady... The man at Stirling was fined for abusing me.”

The work was very hard. This description from a nine-year-old boy was not uncommon: “I walked one mile to school daily and did the chores night and morning. I had to gather eggs, feed the chickens, carry in wood and water... (and) milked cows... I got plenty of horse whip from George who was a bit of a sadist.” An older boy who obviously enjoyed his work wrote: “After I helped to put in the spring crop, we went into the bush and started to peel pulpwood. He felled the trees and I peeled the bark off the poplars... after the bush work we started into the hay... I’ll never forget when he helped me hitch up the horses on a twelve-foot harrow..."

A nine-year-old girl described her mixed experiences: “I learned about tapping trees and making maple syrup and maple sugar. I saw baby lambs for the first time and the sheep being sheared and mother spinning their wool into yarn...” but later she was moved to a farm where she “was put to work scrubbing floors, cleaning stables and milking cows.”

Sometimes the children were treated very badly. One man looking back to his time on a farm in the early 1900s said: “Those seven years were hell. I was beat up with pieces of harness, anything that came in handy... I herded cattle for five years – no horse, no dog – nothing to tell the time by. I had to have the cattle home by 5.30 in the afternoon. If I was late I got beat up. My dinner was put in a 10-pound syrup pail... when it was time to eat it was dry as old toast... I never had a coat when it was raining. Just a grain sack over my shoulders and no shoes.”

There were those who had happy memories of their new life. Let us leave the last word to a man who was sent to Canada in 1894: “Today I pay tribute to the memory of William Quarrier and my foster parents. They gave me shelter, food and care when I was adrift in poverty and despair. I thank him for the day when I first stepped on Canadian soil.”

Boxout: Pioneers of Child Migration

There were various pioneers of child migration, two of whom were women – Annie Macpherson and Maria Rye. They shared a fierce dedication to their cause, but didn’t work together perhaps due to different backgrounds. Maria Rye was from a London Anglican family, while Annie Macpherson was born into a Quaker family in Scotland and became an evangelical.

Maria Rye scorned the limitations imposed on women by Victorian society. She founded enterprises to promote the employment of women, but jobs were few and applications many so Rye decided that emigrating women might provide a solution. Her first trip to Canada with 119 women was successful in placing them as domestic servants and inspired her to send young girls out to Canada, taking them from the gutters of London. She wrote a letter to The Times and with the funds raised bought a receiving Home, an old courthouse in Niagara-on-the-Lake. Her journey in 1869 with 100 girls was the first of many.

When Annie Macpherson moved to London in 1865, she became involved in charitable work in the East End. Her horror in discovering the conditions of the matchbox makers started her on her mission.

She accompanied her first party of 100 boys in 1870 and was offered a Home with rent paid by the people of Belleville, Ontario: “A home of love ... a sweet foretaste to these unloved and uncared for children of their home in Heaven.” But this was not obvious to the children: “We were... taken up to our rooms and put in bed. I was frightened... I cried and cried... I wanted to go to Canada, but when I got there I wanted to go back to Wales...” Rye and Macpherson continued to migrate children until the end of their lives and sent 10,000 children in all.

Dr Thomas Barnardo came to child emigration later than other child rescuers. He sent his first party of 51 boys to Quebec in August 1882 and a group of girls a year later.

In 1884, Barnardo made a trip to Canada and described it as “a fair, garden-like country, yielding abundantly... where a child would flourish in the grand Canadian air.”

Barnardo was an innovator and part of his purpose in Canada was to explore the idea of establishing an industrial farm in the north-west to train older boys. He bought a 10,000-acre farm in Russell in 1887. It was a bleak place but the boys only stayed a year then left to work as farm labourers.

By 1890 when Barnardo made his third trip, the Colonization Scheme was in place. The Canadian government was offering every young man over 18 a 160-acre farm and Barnardo linked this with his farm training programme. He helped young farmers buy implements and seed, which was repaid over time. While life was hard it gave the boys a sense of purpose. For Barnardos in Canada, the end of the era came in 1939 when the Homes were shut. By then they had emigrated 30,000 children.

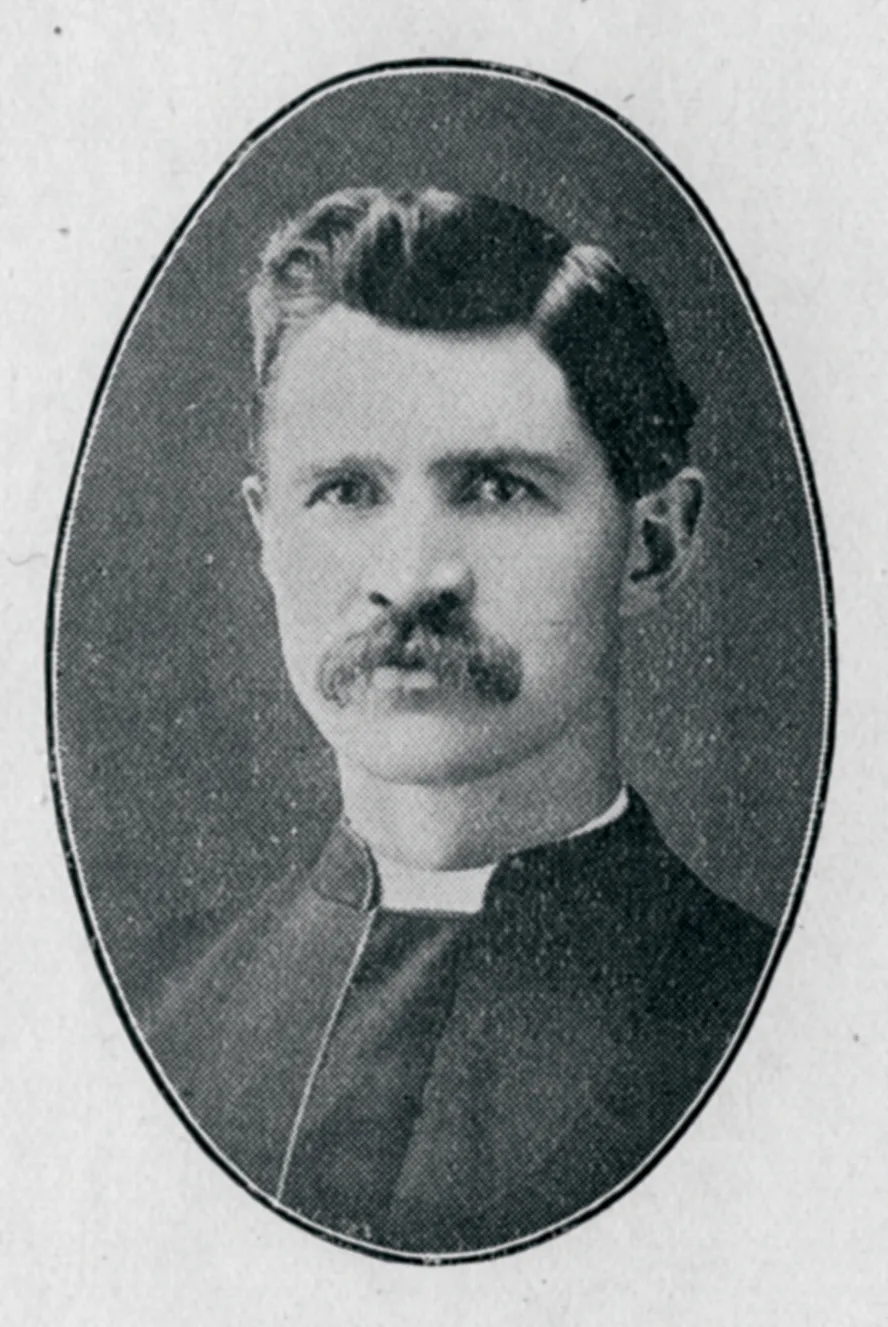

Personal file: Reverend W Bowman Tucker

The life and times of William Bowman Tucker could have been lifted from the pages of a Dickens novel. Born in Stepney, he grew up in Bristol and was orphaned at the age of five. His stepmother sent him to a draconian boys’ school where he described himself as “a prisoner”.

At the age of 12, William was told by a teacher that he had the chance to emigrate to Canada: “your passage will be paid; you will be given two suits of clothing; and found a place with a farmer.” William was taken to London (“a dirty, foggy, narrow-streeted city”) to Hampton Home to learn farming basics. Three weeks later he was waving farewell from a Mersey steamship bound for Canada, feeling “sick at heart”.

On arrival at Point Levis, Quebec, William journeyed on to Ontario where he was selected by a farming family. Although he loved farming and “being free and independent” his days were full of arduous chores for which he was paid a pittance. He was not encouraged to attend school until he was 19 years old, but he shone out and decided to become a teacher. William also became deeply religious at this time and studied to become a Methodist minister before completing degrees at Victoria University, Cobourg.

Remaining in Canada for most of his life, he married and had four children. William founded the Montreal City Mission in 1910 and travelled widely to promote it. He died while visiting Bristol in 1934, believing himself to be “a debtor both to God and to a British humanity.”