Being a worker in industrial Britain was a dangerous business and before the Workmen's Compensation Act there was little protection. All of the country’s heavy industries carried their own hazards: workers in mines, factories, mills, railways and shipbuilding yards were regularly killed or injured.

Some of the most deadly disasters are well-known: 439 miners were killed in an explosion at the Universal Colliery in Senghenydd, South Wales, in 1913, in the worst mining accident in the UK’s history. But everyday injuries were just as common, and many workers left their jobs with an industrial injury or disease.

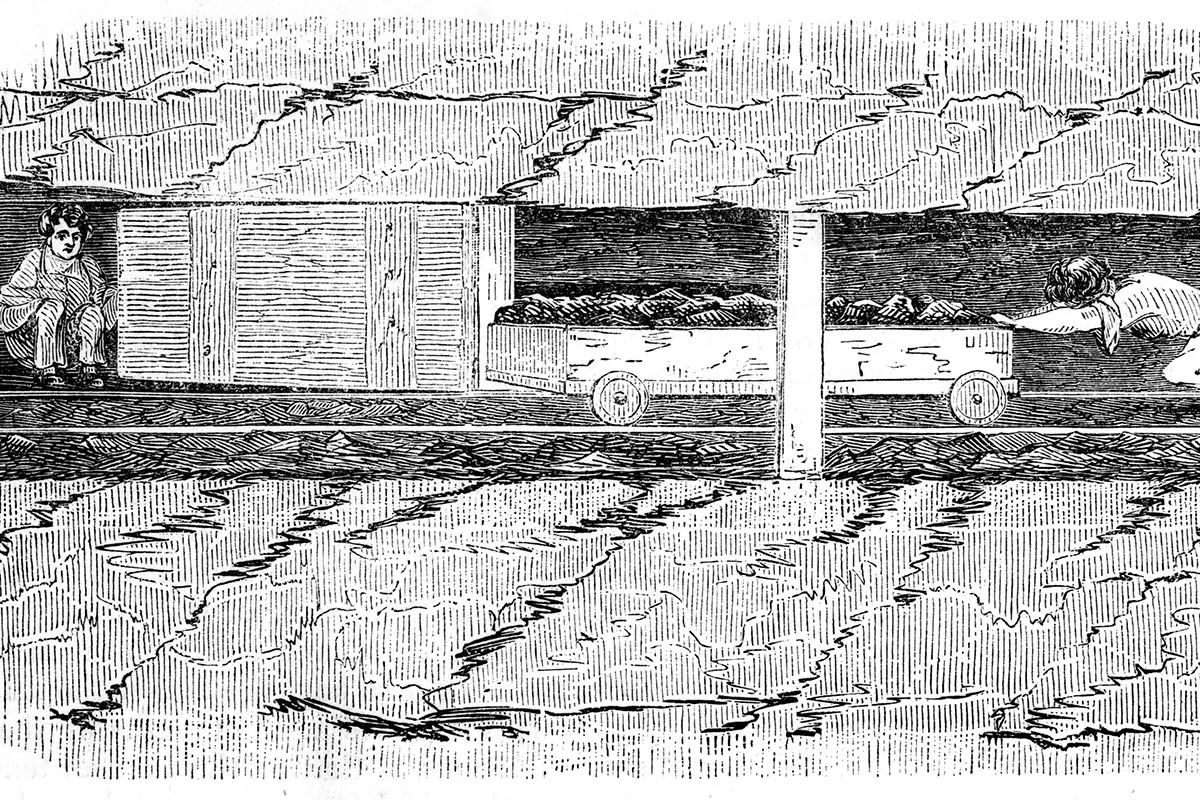

Throughout the 19th century, commissioners and reformers drew attention to dangerous conditions and exploitative working conditions in these workplaces. Inspectors were installed to regulate safety, and legislation designed to curb the widespread use of child labour. The 1833 Factory Act banned children under the age of nine from working in factories, while the 1842 Mines and Collieries Act ruled against women and children working underground in the mines.

Yet it would take until the last two decades of the 19th century for employees to finally get state compensation for work-related injury and disease. But how effective were the Acts and what was it like for a disabled worker in these dangerous industries?

The Employers' Liability Act of 1880 and the Workmen's Compensation Act of 1897

Two major acts of legislation were passed that brought in state and employer responsibility for accidents for the first time. The Employers’ Liability Act of 1880 made companies liable for accidents that occurred at their workplaces due to faulty machinery or the negligence of employers or superintendents. In 1897, the Workmen’s Compensation Act gave workers the automatic right to compensation for the first time. Both acts were fiercely condemned by employers, many of whom feared that giving money to disabled employees would cause financial pressure on their industries.

However, soon after the legislation was passed, the holes began appearing. A clause in the 1880 Act allowed for ‘contracting out’ of employers’ duties, meaning many set up alternative schemes on their own terms. Likewise, not all hazards were covered: diseases caused by regular exposure to coal dust or lead were difficult to trace back to their source so it was easy to deny responsibility, especially if the employee had worked in multiple places or the workplace had since closed down. This could leave a number of workers with neither a job nor an income from compensation.

A colliery manager in Northumberland told the Sankey Commission in 1919 that: “If a miner is disabled through accident or ill health occasioned in the mine and proved to have been so occasioned, then he receives compensation under the Workmen's Compensation Act; but short of that, if a miner, through a breakdown of health, quite apart from that, short of his being on a permanent relief fund or some other fund, of course there is no means of compensating him.”

Another major problem was the insistence that accidents must have been “in and around” the place of work. Cases sprang up that defied these vague terms, such as workers being injured on their way to work. Writing in 1905, the lawyer Alfred Henry Ruegg highlighted two particularly bizarre cases he had seen: “One was the case of a pit boy who contracted St Vitus Dance after being frightened by a colliery cat; the other was a case of a miner who suffered blood poisoning after a mouse ran up his trouser leg and bit him.”

"A miner suffered blood poisoning after a mouse ran up his trouser leg and bit him.”

One version of the Bill was thought to have created so many court cases that it earned the nickname in Parliament of the ‘Lawyers’ Employment Bill’.

Medical assessments for workplace injury claims

For disabled workers, claiming compensation meant regular – often contradictory – medical assessments and endless meetings and paperwork with doctors, colliery agents and insurance companies. A trip to the doctor was compulsory under the Workmen’s Compensation Act, and employers often insisted on several. Complications emerged about what caused the accident and who was liable. One miner with a bruised back was paid compensation for a year until another medical check-up decided that “due, in the first place, to his accident, 50 per cent; in the second place, to bad teeth; and in the third place to insufficient use or effort to get well, 25 per cent. Each.”

Gradually, issues started to emerge about doctors’ power to take away compensation. A 1916 government memo revealed that: “Complaints have been made by workmen that this power [to submit to medical examination] has been used oppressively, especially by agents of insurance companies, by insisting on repeated examinations, and otherwise exercising undue pressure, with a view to drive injured persons into accepting small and inadequate sums in satisfaction of their claims.”

Absence from employment could cause serious financial troubles. Compensation amounts never matched workers’ original wages and took two weeks to become compensable. “I think I waited nearly a month before they started to pay anything,” remembered the former miner BL Coombes about his knee injury in his 1939 autobiography. “They cannot seem to realise that most of us are living on our next week’s wages, and that even a day out of that means that someone must go short.”

“They cannot seem to realise that most of us are living on our next week’s wages."

The limits of compensation meant that these Acts never replaced the patchwork of welfare that workers had set up long before their introduction. Friendly societies were common throughout British industry and operated as worker-run organisations that provided accident and sickness cover as well as benefits to old-age members and widows, in exchange for a regular contribution. But these had rules, too. Visitors checked up on sick members missing work, and others prevented abuse by setting moral rules.

One society for enginemen in Durham banned benefits for anyone who brought upon himself sickness by “fighting, leaping, running, footballing, or any other acts of bravado, or immorality”.

Welsh Medical Aid Societies

Some later worker-run initiatives were genuine innovations. The Medical Aid Societies set up by and for coal and steel workers in South Wales provided health cover, equipment and relief to disabled members. One enthusiastic member of the Tredegar Medical Aid Society was Aneurin Bevan, whose experience with the society partly informed his vision for the National Health Service.

As the coal industry began to decline after the First World War, many of these organisations struggled for funding. When the Ebbw Vale Workmen’s Medical Society could not provide the money for a pair of crutches for a member’s daughter in 1921, one of its members volunteered to make a pair themselves.

This was not uncommon. Financial help often came from much less formal settings, and involved communities coming together to ensure injured workers could survive. Jim Griffiths, the Welsh Labour politician, told Parliament in 1945 that he “still [had] boyhood memories of buying a 3d raffle ticket to provide a peg-leg for a miner”.

Communities came together to ensure injured workers could survive.

A last resort was the Poor Law, which could mean a visit to the workhouse or ‘outdoor relief’ paid out. This was feared and hugely stigmatised. As the Welsh labour activist Elizabeth Andrews remembered: “There was a real dread of being buried by the Poor Law in a pauper’s grave.”

It was hardly generous, too, and many claimants had to supplement state handouts with family income. This often meant passing on ‘breadwinner’ duties to sons who followed their fathers into the industry, but not always. One disabled Poor Law claimant from Bedwellty in South Wales, in the middle of the bitter 1926 coal lockout, had two sons listed as unemployed. He relied on a mixture of Poor Law relief and the income from four daughters working at the laundry.

Unions join the fight for work injury compensation

Unions became more involved in fighting for compensation into the 20th century. The Trades Union Congress regularly discussed the legislation and individual trade unions began devoting departments and staff solely to compensation. Many also branched out into provision of artificial limbs and other assistive technology.

Many disputed compensation cases were treated personally, such as the “gross injustice” described by an agent of the Durham Miners’ Association of a worker who had injured his back and hip in 1903. It took 13 years for any kind of success with compensation. As the agent wrote in 1918: “He has been deprived of his compensation for 13 years, and he has had to bring up his family practically on the Parish.

“The effect upon a man’s general health in having to live under such a great injustice must have been enormous, but to witness his family living under straitened circumstances as compared to what might have been for them under normal circumstances, and to be further deprived of any little assistance he was legally entitled to must have robbed him of any little pleasure he might obtain in life.”

Disabled employees returning for work

Given the dangers of working in heavy industry, it is perhaps surprising that many disabled employees went back to their place of work. They usually would not be able to return to heavy labour or underground, so instead took up ‘light work’. This might be administrative work, looking after light machinery or equipment, or in the case of coalminers, ‘surface work’ like picking coal from conveyor belts. These jobs were often based on good relationships or a sense of paternalism. But they were most often dull, badly paid and lower in status than the injured workers’ previous roles.

Some who did not succeed at the ‘light work’ were financially punished. A coal hewer at Hetton Colliery near Durham, is an example of this. He had a leg amputated after being run over by a set of tubs at work. Eventually the colliery management refused to pay full compensation because he was judged ‘fit to work’ (a phrase still common in disability assessments to this day).

Eventually the colliery management refused to pay full compensation because he was judged ‘fit to work’ (a phrase still common in disability assessments to this day).

With the Depression in the inter-war years, work became more and more scarce and disabled workers were often the first to go. The MP for Whitehaven talked of miners being given “light work, but it usually happens that there is not a vacancy, and he goes on, neither a sick man nor a whole man, and that is his condition permanently in the mining industry”.

Some workers who did not go back into their industry changed careers or took up hobbies. Many schools in mining districts, for example, employed disabled ex-miners as teachers. As for hobbies, these often subverted the macho world of work.

In an interview, one blind former miner talked about how his passion for gardening helped him connect to his son: “I had to go and sit on the garden path you see, and he would put a line down and I would go along the line and plant seeds like beetroot, and things like that, with finger measurement along his line.”

The Workmen’s Compensation Act was active throughout the first half of the 20th century, but it could not last in that form. William Beveridge’s landmark 1942 report Social Insurance and Allied Services – a key document in the making of the welfare state – slammed the existing compensation as “below subsistence level for anyone who had family responsibilities or whose earnings in work were less than twice the amount needed for subsistence”.

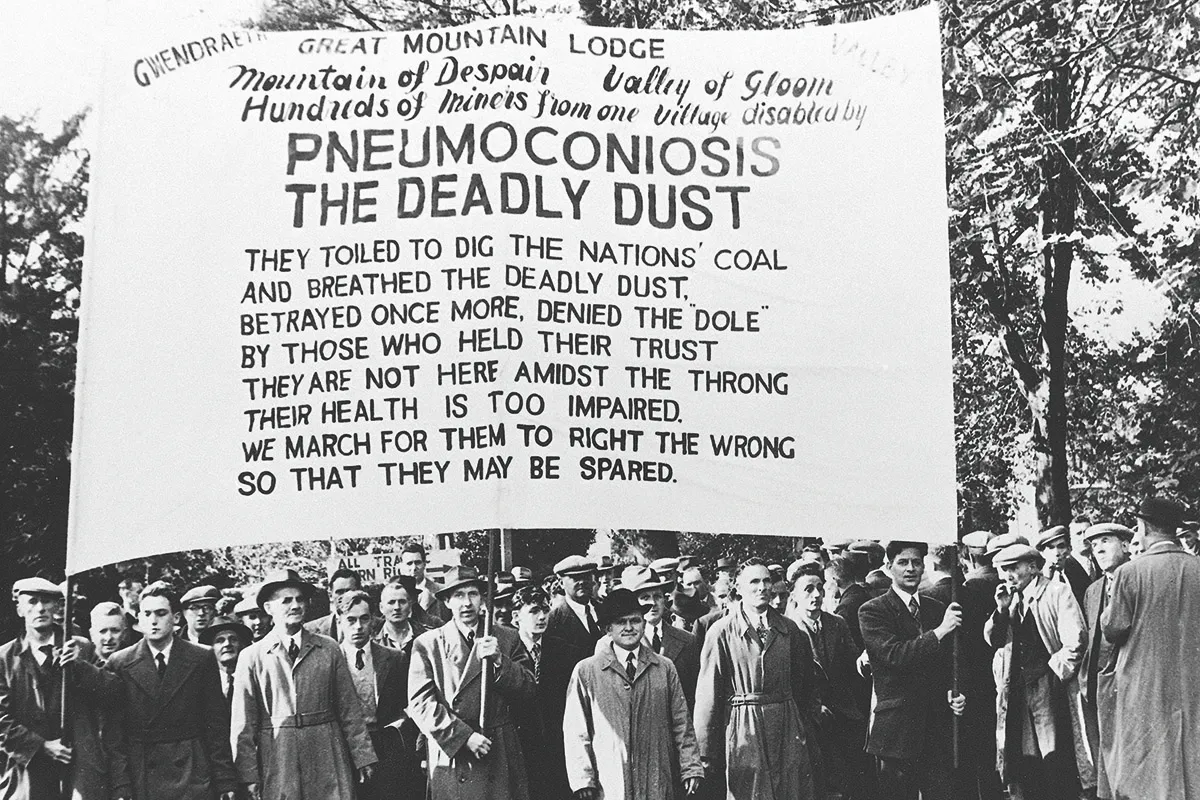

The National Insurance (Industrial Injuries) Act 1946 effectively replaced it with a compulsory insurance system for the first time. But the problems did not go away for industry: the safety of workplaces was still a concern, and campaigns like the National Union of Mineworkers’ 1952 march against pneumoconiosis brought attention to injured and diseased workers still denied justice.

Life on compensation simply was not enough for the majority of disabled workers, who returned to work if possible or turned to a wide variety of sources to make ends meet. But what is most important is that disabled workers carried on living rich and varied lives after their accidents and contracting diseases. Their experiences must not be lost to history.