The headline “Suspected murder on board ship” grabbed Hazel Garas’ attention. She was doing a general search of old newspapers for her great great grandfather William Oliver Ross, and found him mentioned in the Newcastle Courant on 21 June 1878.

“William was the mate of a fishing boat called Milo,” Hazel explains. “The article revealed a gruesome story regarding his brother-in-law, John Perfect, who died on board ship. I was intrigued because nobody in my family had mentioned the possibility of a murder.”

Hazel, who is a retired teacher from High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire, began tracing her genealogy 20 years ago. “Seafaring runs in our blood. My father was a fisherman and served in the Merchant Navy.

“William Ross was born in Perth, Scotland, in 1850, and moved to Great Yarmouth in Norfolk with his family. His father was a barrack labourer in the Royal Naval Hospital there.”

William married Ann Perfect in 1873, and they settled in Grimsby where there was ample work in the burgeoning fishing industry. Ann’s father Horace Perfect was an engineer who lost his job and was made bankrupt. He deserted the family, and Ann’s younger brother John was forced to enter the workhouse.

William must have helped John, for in 1878 he joined the crew of Milo as an apprentice. He was aged 19 at the time.

“The vessel was a ‘smack’, – a traditional wooden fishing boat with sails. Life at sea was tough, and crews were often away for at least eight weeks. The men had to haul up nets containing as much as half a ton of fish. The catch was gutted and transferred to another vessel that would return to port.

“Sleep was only possible in short snatches, and smacksmen often slept in their wet clothes. There were no washing or toilet facilities, except for a bucket. ‘The cabin stank of bilgewater, cooking, cod livers and unwashed humanity’ was one contemporary description.” Friction could easily arise in such difficult conditions.

Milo set sail for the North Sea fishery on 20 April 1878 crewed by Captain Ashwell, William Ross, John Perfect and two other apprentices, George Packett and George Bailey.

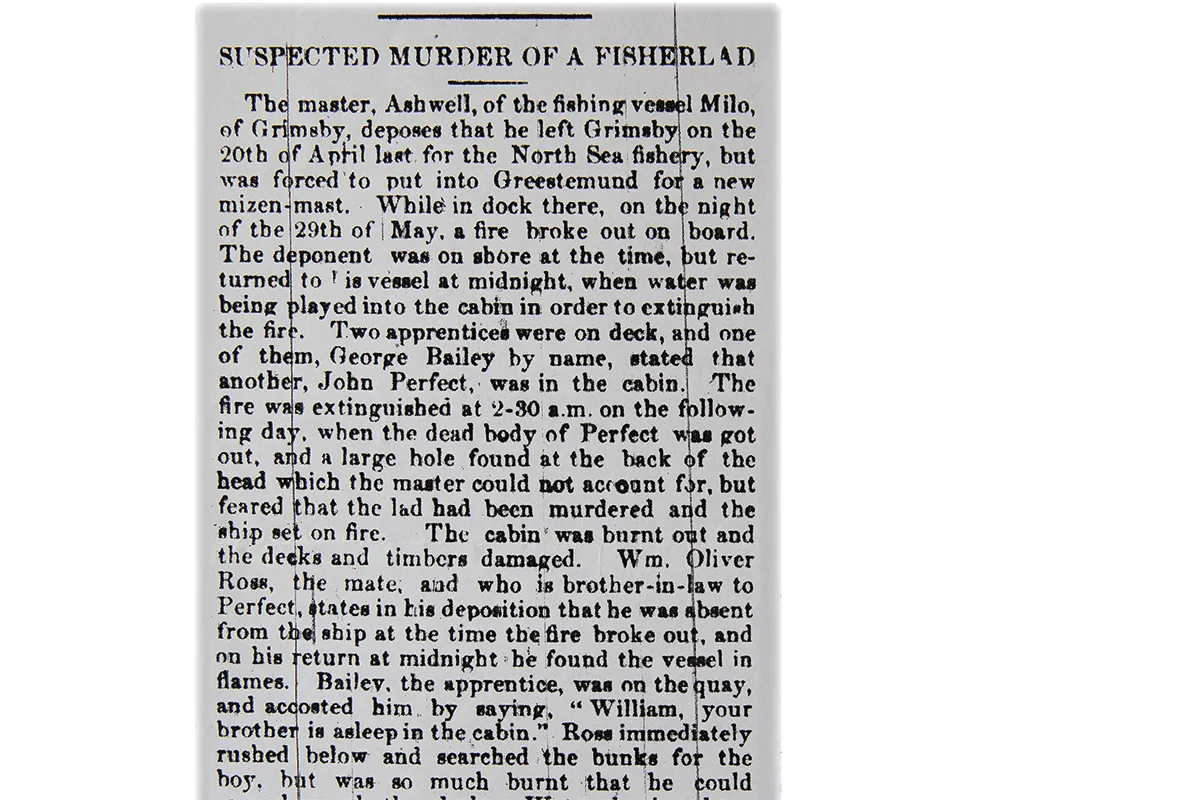

The article in the Newcastle Courant quoted a report from the insurers Lloyd’s of London, which explained the dramatic events. The smack’s mizzen mast had broken in a collision, so the captain was forced to dock at Geestemünde, in the German port of Bremerhaven.

On the night of 29 May, a fire broke out on board the ship. William was ashore at the time and returned to find the vessel in flames and a fire engine spraying water into the cabin.

Both Georges were on deck and George Bailey exclaimed, “William, your brother is asleep in the cabin!” William rushed below, braving the flames and thick smoke to search for his brother-in-law. His efforts were in vain, and he was so badly burned that he could barely reach safety.

The fire was put out at 2.30am and John’s body was removed from the cabin. There was a large hole in the back of his head.

Captain Ashwell concluded that it could only have been inflicted by a marlinspike: a long, steel tool used in marine ropework. He also feared that the lad had been murdered and the ship set on fire.

The captain feared that the lad had been murdered and the ship set on fire

“It was sobering to read of John’s demise at such a young age, and of the injuries that William sustained. No charges were made despite the suspicion of foul play, and the case was closed. Naturally, I was keen to discover what had happened on the Milo.

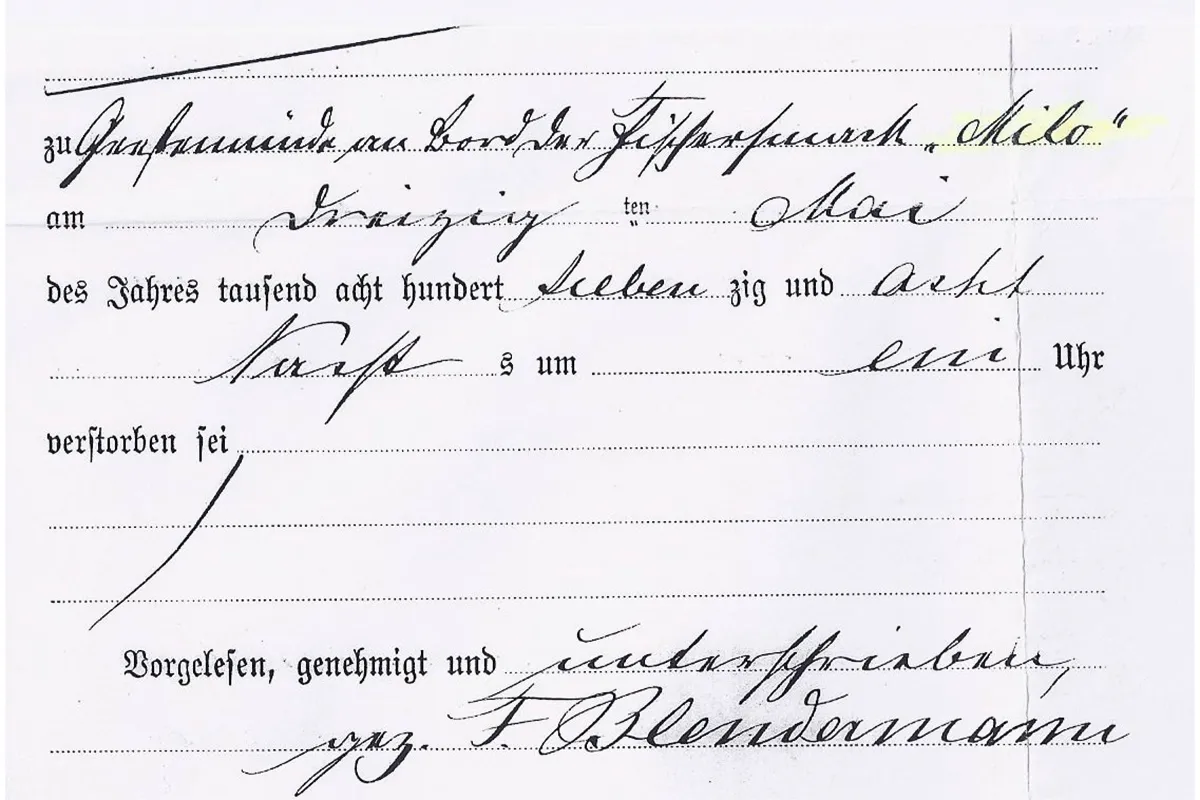

“First, I requested a search of the Lloyd’s Marine Collection at The Guildhall in London, but the archivist couldn’t find any clues. I have a friend in Bremen, Matthias Mangels, who has helped me a lot with the case. He suggested that I contact the archives in Bremen and gave me their address. They sent two newspaper reports from 1878, and John’s death certificate.

“The articles explained about the fire, and surprisingly gave the cause of death as ‘suffocation’. They also revealed that John’s funeral took place in Bremerhaven on 1 June 1878, and that most of the crew left three days later. It was very perplexing that the German newspapers made no mention of suspected foul play, or of the hole in John’s skull.”

Next Hazel visited The National Archives at Kew (TNA) to see if there was a Board of Trade report, or information from the British consulate in Bremen. “I asked the archivists for assistance, and they found a large collection of correspondence about the case.

“The file contained letters from Bremen’s British consul, Wilson King, to the 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, the foreign secretary. I was probably the first person to look at these files since they had been archived.”

In a letter dated 3 July 1878, King told Salisbury that the only knowledge he had of the case was gleaned from the newspapers. None of the crew had contacted the consulate.

The registrar in Bremen had taken statements from the crew, who said that the fire was caused by a cigar or cigarette. As the captain went to sound the klaxon, a tin of paraffin was knocked over which intensified the flames. George Bailey is referred to as the “prisoner” in these statements, so it seems that he was arrested for starting the fire.

“This report contradicted the comments made in the Courant. Why hadn’t the crew contacted the consulate to pursue the matter?”

The police closed the case after the crew left Bremerhaven on 4 June. However, documents in the TNA file revealed that the Board of Trade had investigated the case, interviewing several witnesses under oath on 1 July.

“They were Johann Rhode, a local innkeeper; Frau Muller, who cleaned up John’s body; Herr Ochs, the undertaker; and the physician Dr Hartwig. They sound like protagonists in a German tragedy.”

John’s body was moved to Rhode’s inn until the funeral. The crew also stayed there while Milo was being repaired.

Rhode’s testimony was most revealing: “I was surprised to see the dead body bleeding heavily out of a wound on the back of his head. Knowing that scalds do not bleed, I made the physician Hartwig pay attention. He examined the body and asked, ‘How is this possible?’ ”

Rhode said that he presumed that John had woken during the fire, hastened from the cabin and hit his head falling downstairs. Dr Hartwig concurred and signed the death certificate, which allowed John to be buried.

The crew of the Milo stayed at the inn until the burned-out smack was released. They sailed home without William Ross, who travelled to Hamburg and returned to Grimsby on a boat transporting migrants.

During his time at the inn, William made some chilling statements to Rhode, who quoted these in his testimony. “Ross presumed that John Perfect was not burned in the ship by accident, but that he had been stabbed by the cook George Bailey, who afterwards set fire to the ship.

“This was because quarrels often took place between Bailey and Perfect. William had heard Bailey threaten John that he would find an opportunity to kill him, even if it cost him his life.”

William also said that John’s body was in the same place where he always slept, so it was unlikely that he got up and fell. Also, the marlinspike was found in the cabin where it wasn’t usually kept. Rhode asked William why he hadn’t informed the court, and he replied that the matter would be settled in England.

Clearly the captain and William had grave suspicions regarding John’s death, so why didn’t they share these with the German police? Rhode and Dr Hartwig both voiced the impression that the crew wanted to leave Bremerhaven as soon as possible.

“They were desperate to return home. They must have feared imprisonment in a foreign land where they didn’t speak the language. William should have reported his suspicions to the British consul, but I’m not him in 19th-century Germany. He informed the authorities on his return, but there was little that they could do.

“Since then, more intriguing evidence has come to light. On Ancestry, I found that George Bailey was indentured to William Ross as an apprentice on a ship called the Speculator in 1876. A year later, the indenture was cancelled.

“No reason was given, but it may have been due to bad behaviour. Clearly, William had had prior dealings with Bailey that made him believe that the lad was capable of murder.

“In my opinion, the testimonies and evidence support William’s belief that George killed John. There may be something in a box on a dusty shelf in an archive that will one day shed new light on the tragic case of John Perfect.”

Do you have a family story to share with Who Do You Think You Are? Magazine? Email us for your chance to be published in the magazine!