Taken on 2 April 1911, the 1911 census was the occasion for unprecedented levels of excitement, because radicals plotted to sabotage the exercise.

The campaign for votes for women had been heating up in 1911 with both ‘militant’ and ‘constitutional’ groups battling for public attention and influence over the Government. Now both wings of the suffrage campaign were prepared to protest at the lack of representation for women by disrupting the census. There were two types of protest: evaders who hid from the enumerators, and resisters who filled in the form with expressions of defiance.

Women wrote their anger at being denied civic rights across the page with such protests as “Women do not count: neither shall they be counted”. An enumerator in Lowestoft wrote of a common experience: “It was handed me not filled up, but with the words ‘No votes for Women – No information from Women’ written across the schedule.”

Women wrote their anger at being denied civic rights across the page with such protests as 'Women do not count: neither shall they be counted'

The best known of the evaders is Emily Wilding Davison, who spent census night hiding in a broom cupboard in the House of Commons. She was later to find posthumous fame for throwing herself in front of George V’s horse at the Epsom Derby in 1913.

The protests were led by the Women’s Freedom League, a breakaway from the militant Women’s Social and Political Union (‘suffragettes’). Some women went to dance halls so that they were not in private houses where they would be enumerated. A cheery group of young women stayed up all night at the Aldwych Roller Skating Rink, while older protesters played whist through the small hours. Fleets of caravans full of evaders went out to common land so that they could not be counted. The sizeable Denison House in Manchester was designated ‘Census Lodge’, and housed 208 evaders.

Enumerators turned detective and relied on information from neighbours or the police, or just estimated the number of people at a place.

However, a number of radicals disagreed with the boycott, feeling that the Government was doing much good with its National Insurance Act and battle with the House of Lords. They believed that the data from the census would be used for socially beneficial legislation which relied on accurate statistics.

Supporters claimed that at least 100,000 people had resisted, but in reality there were probably fewer than 10,000.

The government wisely decided not to prosecute the census rebels, since fining and sending suffragettes to prison had not been a great success in dissuading them from activism. Ministers played down the protests, saying that any under-enumeration of women was “entirely negligible”. For us, writes historian Jill Liddington, “The 1911 census offers for the very first time a unique opportunity to eavesdrop into the heart of Votes for Women homes.”

Feminism was demonstrated in other ways too, with a number of women describing their occupation as ‘slave’, ‘domestic slave’ and ‘slave of the family’, or simply as ‘suffragette’ or ‘suffragist’, as Michelle Keegan found in her episode of Who Do You Think You Are?

How many people were in the 1911 census?

The 1911 census found that there were 34,043,076 people in England, 2,032,193 in Wales, 4,759,445 in Scotland and 4,381,951 in Ireland. There were 1,068 women for every 1,000 males, the same ratio as in 1901.

What questions were asked in the 1911 census?

The 1911 census showed a preoccupation with eugenics, a recurrent theme of public debate in the early 20th century. An interest in fertility was also a concern, because the declining birth rate and an increase in emigration led some thinkers to believe Britain would become underpopulated and fall behind the rising economies of such nations as Germany and the USA.

Thomas Stevenson, the superintendent of statistics, said that detailed questions about children would show “the prospects of fertility for any given union of husband and wife of specified ages”. Wives were asked the number of years that they had been in the present marriage, and the number of children who had been born. There was also an interest in child mortality with a new, melancholy ninth column that asked about “children who have died”.

The final column now asked for more information about infirmity. Entries were requested for the deaf or deaf and dumb, blind, lunatic, imbecile or feeble-minded, along with a request to state “the age at which he or she became afflicted”.

As well as someone’s occupation, the census asked the industry in which they were employed and the name of that body if they were employed by the government or a public institution. There were more employment categories too; the census was specific on, for example, five categories of iron-foundry workers. It has never been so easy to separate your moulder and core-maker ancestors from your fettlers and oven-men.

Some job descriptions are deceptive, however. The profession of ‘billiard marker’ was seemingly flourishing with 11,139 noting it as their occupation in England and Wales in 1911. These were men who allocated tables, kept scores and looked after the equipment in billiard halls. Billiards was a popular pastime, but there had been no increase in billiard halls commensurate with the increase in billiard markers. What there had been was an increase in amateur teams playing rugby and football, which had become massive spectator sports around the turn of the century.

The profession of ‘billiard marker’ was seemingly flourishing with 11,139 noting it as their occupation

In order to maintain their amateur status, players could not be paid for their work on the field. A let-out clause, however, allowed them to be given ‘broken-time’ payments for time that rugby or football had taken them away from their profession. Billiard halls were busy at the weekend when matches were played, so anyone working there during the week could claim money from their clubs for time off for playing in amateur leagues.

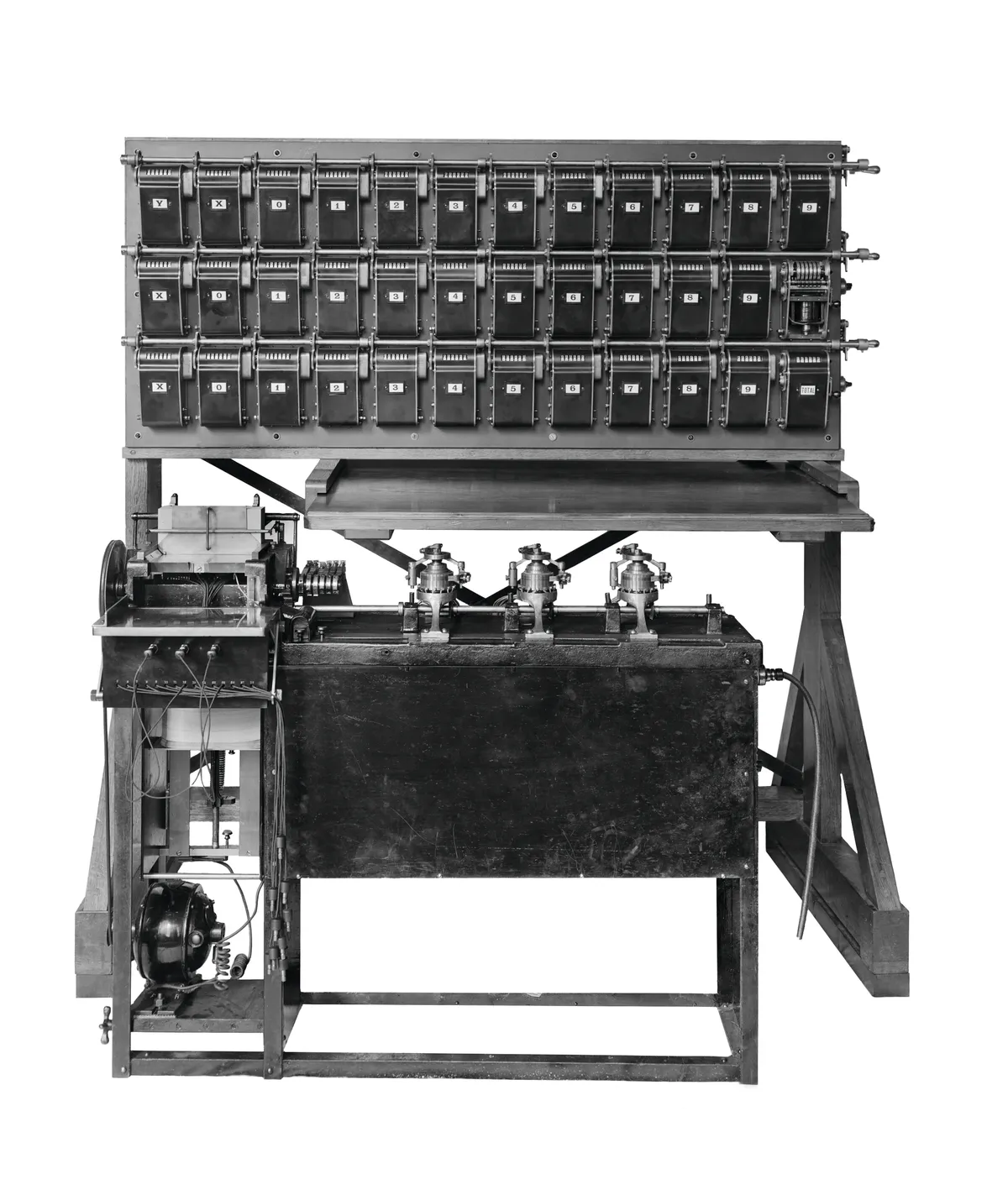

The 1911 count was also remarkable for the first use of data-processing technology. Electrically driven card-counting machinery was made by the British Tabulating Machine Company and operated with cards with punch holes. An army of coders, clerks and punchers worked to process the data at the census headquarters in Millbank. It was the greatest technical innovation until the census migrated online in 2021.

Where to find 1911 census records

The 1911 census is the first census where the household schedules were kept. Virtually the entire population was sufficiently literate to fill in the forms, so you can now see an ancestor’s handwriting rather than that of an enumerator on the searchable household returns. For many family historians this will be the first time they will look at a document their ancestor has written.

Ancestry £

Index (including occupation) and images for England and Wales. Census summary books can also be searched. Irish census index links to images on The National Archives of Ireland.

The National Archives of Ireland Free

Index and images for all of Ireland, which can be searched by occupation, religion etc.

FamilySearch Free

Index shared with Findmypast for England and Wales. Occupations not indexed. Irish census index links to images on The National Archives of Ireland.

Findmypast £

Index and images for England and Wales with occupations indexed. Irish census index links to images on The National Archives of Ireland. There is a free article explaining the occupation codes in the 1911 census here.

ScotlandsPeople £

Only index and images of the 1911 census for Scotland. Images are from the enumerators’ books, not individual household schedules.

TheGenealogist £

Index and images for England and Wales (with occupation). The index is shared with Ancestry.