The popularity of DNA testing for family history has soared recently. In January 2019 GenomeWeb reported that approximately 30 million people worldwide would have taken a DNA test by December 2018. Tests are now cheaper than ever, while also being easy to buy online and even on the high street.

It is through these tests that many of us (including me) have discovered that we have Jewish ancestry. This raises the question of how accurate these results are, and how we can find out more about our Jewish ancestors.

Read our expert guide to choosing the right DNA test for you.

Firstly, we should look at the tests themselves. Most tests sold in the past year were for autosomal DNA (atDNA), not Y-chromosome DNA (Y-DNA) and mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). These can be taken by men or women, and check the DNA inherited from autosomal chromosomes.

You will have segments from all your ancestors up to at least your 3x great grandparents. However, as you go further back you will find there are some ancestors you share no DNA with.

Finding DNA relatives (cousin-matching) and exploring ethnic origins tend to be why family historians buy DNA tests. Yet both these aspects of genetic genealogy can be misunderstood. We may find some surprises within our reports.

This confusion can be complicated by articles and anecdotes shared on social media about people’s experiences of DNA testing. I have lost count of the newspaper reports I have read about testers finding long-lost parents or siblings through DNA tests.

Some of these testers were looking specifically for a missing relative, but there are growing numbers of reports of recipients of Christmas presents or those with a general interest who do not fully understand what their test may reveal.

How do I know if I have Jewish DNA?

DNA tests can help people confirm a relationship with others, but they can also give clues as to your ethnic origins and this can include hints that you have Jewish DNA.

While the DNA evidence of a close relative can be proved, the estimates of where our ancestors originated are often clouded in confusion.

It is important to remember that our DNA is inherited randomly from our ancestors. Siblings can show a different inheritance in a test – for example, when a brother has a larger estimated percentage of Ashkenazi Jewish DNA than his sister. This is because of him having inherited more DNA from their most recent Ashkenazi ancestor (for example a great grandparent).

This random inheritance means that we don’t always get exactly 12.5 per cent of DNA from a great grandparent. For example, if you have an Ashkenazi great grandparent, the percentage of Ashkenazi DNA you inherit may form only 8–10 per cent of your ancestry.

Currently, the ethnic origin part of DNA test results is not an exact science, and there are continual developments.

If you took a test over a year ago, you may have noticed changes to your ethnic origins even in this short period. AncestryDNA, for example, roll out improved algorithms annually at least.

Another problem is specific to Jewish DNA – it is based on an ethnic diaspora or population community group, rather than on geographic origins. This makes it an especially tricky area to research.

The Jewish diaspora

From the 1880s until the early 20th century, Britain saw swathes of Jewish refugees escaping the Pogroms of Eastern Europe.

Approximately 140,000 Ashkenazi Jews settled in Britain during this period. Most lived in major cities, such as London, Manchester and Leeds. Others, were merchants who traded in smaller urban areas, such as Bristol and Merthyr Tydfil.

Such a rapid influx of migrants was not welcomed by many. The 1905 Aliens Act introduced immigration controls for the first time. Many Jews experienced prejudice and discrimination, and were keen to assimilate.

Where people did intermarry, the Jewish side of the family may not have been mentioned to future generations. For this reason, many of us have never been told of our Jewish ancestry until we discover it via DNA testing.

What is the best DNA test for Jewish ancestry?

The largest companies that provide tests for cousin-matching and ethnic origins are FamilyTreeDNA, AncestryDNA, MyHeritage, Living DNA (with Findmypast) and 23andMe.

I have tested with FamilyTreeDNA and Ancestry, and uploaded my raw DNA data to MyHeritage, LivingDNA, 23andMe and the free site DNA Land.

Living DNA is keen to stress that its results focus on where people have lived, rather than on ethnic population groups such as Jewish Ashkenazi. Therefore Jewish DNA is not flagged up in the company’s algorithms.

To illustrate the differences between the testing companies, here are my Ashkenazi Jewish percentages from the five sites:

- FamilyTreeDNA: Ashkenazi, 7 per cent

- Ancestry: European Jewish, 9 per cent

- MyHeritage: Ashkenazi Jewish, 10.3 per cent

- 23andMe: Ashkenazi Jewish, 11.4 per cent

- DNA Land: Ashkenazi, 13 per cent

My Ashkenazi results from these sites therefore range from 7 per cent to 13 per cent. From my paper research, I had identified a gap in my family tree (through illegitimacy) of an unknown great grandfather.

The identities of my other great grandparents have been confirmed through paper research and cousin matches from my various DNA tests. The 7–13 per cent range of my Ashkenazi ethnic origins fits well with the amount of DNA I would have inherited from an individual great grandparent.

Some of the websites have tools that can be particularly helpful for working with Jewish results. For example, 23andMe offers a ‘Your Ancestry Timeline’, which indicates how many generations ago your most recent ancestor was for each population (ethnic group).

According to this, I “most likely had a grandparent, great-grandparent, or second-great-grandparent who was 100% Ashkenazi Jewish. This person was likely born between 1860 and 1920.” This also seems to confirm that my Jewish ancestry could come from a great grandfather.

My 'lost' Jewish great grandfather

The search for my Jewish great grandfather progressed quickly when two fairly close DNA matches appeared on MyHeritage and Ancestry.

I soon discovered that they were an uncle and nephew. Using 23andMe’s Chromosome Browser to separate the Ashkenazi sections of my DNA from the non-Ashkenazi, I compared them with the sections of the uncle’s DNA that match mine exactly within the Ashkenazi sections.

Luckily, I could narrow down the search as the uncle and nephew are only part Jewish, with the uncle having only one Jewish grandparent. The evidence indicated, therefore, that I am related to this Jewish grandparent.

This reduced my potential matches to one family with four brothers. Communication with members of the family revealed photographs and details of the lives of each brother.

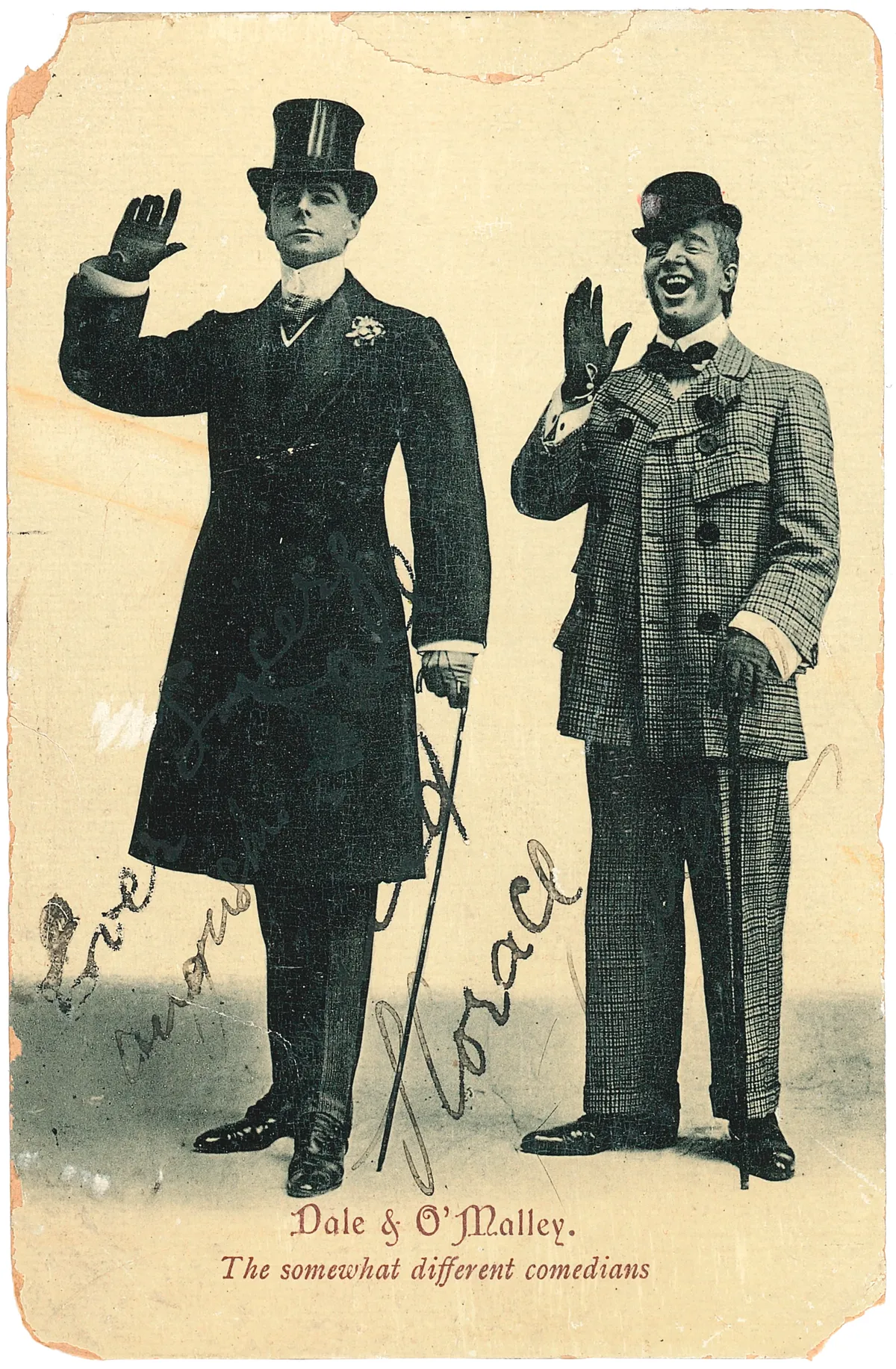

This led me to narrow down my great grandfather to Victor Dale (1881–1947). Victor led an exciting life, including a theatrical career as the writer and straight man in a comedy double act, Dale and O’Malley.