The discovery of agricultural labourers ( or 'ag labs' for short) is commonplace in most researchers’ family history. While researching them may seem challenging because of a lack of written records, you can find out more about them in a surprising number of common sources.

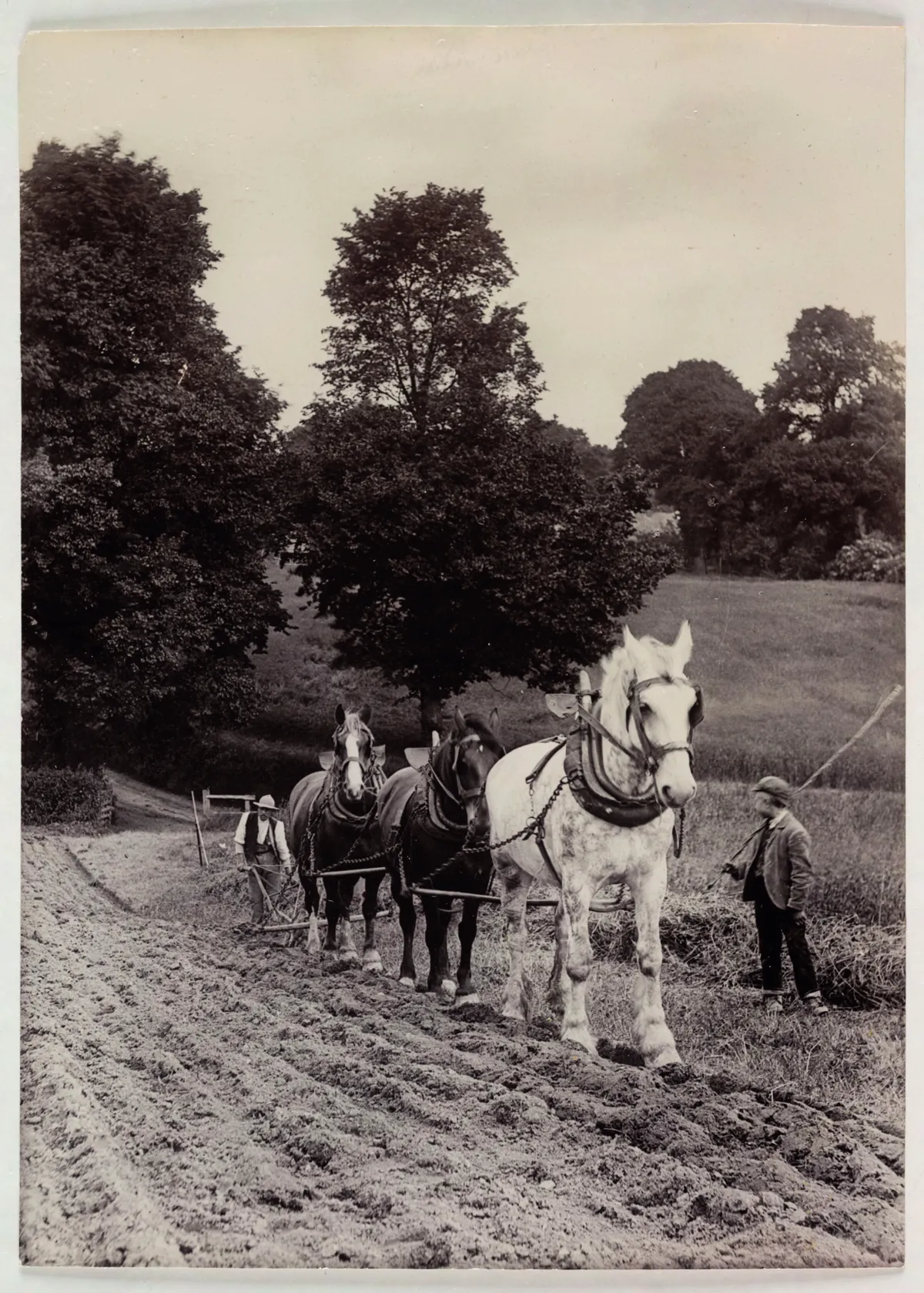

The agricultural industry in the 19th and early 20th centuries was labour-intensive and seasonal. Many agricultural labourers did not have security and were employed on a casual or annual basis, having to supplement their family income by women and children working in cottage industries such as lacemaking or straw-plaiting.

During Queen Victoria’s reign about half of the population relied upon agriculture for their livelihood despite England being a progressive industrial society. Many local occupations supported the agricultural community including blacksmith, wheelwright and miller, each of them reliant upon the prosperity of the community which suffered a number of economic agricultural depressions.

During Queen Victoria’s reign about half of the population relied upon agriculture for their livelihood

Commercially farms were linked by a network of cattle markets and the annual hiring fairs. Records of the hiring fairs held in local record offices provide information about your ancestors who changed their employment.

The countryside economy was affected by mechanisation cutting the labour force by about two-thirds, but it was not until the late 1880s that the real impact was felt. Throughout the 1830s and 1840s there was unrest among agricultural communities with the burning of haystacks and machinery culminating in the Swing Riots because of consistently low wages and the threat of unemployment. Continuing actions resulted in the establishment of the National Agricultural Labourers Union in 1872. Despite a prolonged strike in 1874 and various depressions the union prospered, and by the end of the First World War membership exceeded 100,000.

Many agricultural labourers lived in villages predominantly controlled by major landowners who were their employers, justices, landlords, churchwardens or Poor Law administrators. Life for the agricultural labourer was never easy. Most lived in small two-bedroomed rented or tied cottages, provided by the estate employing them. Families were normally large so the labourer, his wife and younger children slept in one bedroom and the older children slept in the other, with male and female areas divided by curtains. Children would also be boarded out with relatives, or became domestic servants or apprentices. The one living room/parlour was the centre of family activities. Most cottages had a small workroom/scullery where tools, fuel and boots were stored, and an adjoining allotment where the family could grow vegetables and perhaps keep a pig.

Up to the middle of the 1850s the labourers wore traditional smocks which, because of mechanisation, became unsuitable and were replaced by more serviceable workwear. The pattern of smocking often indicated their calling as a ploughman, horseman, dairyman or hurdler. Most wore hats as sunshades and rainwater deflectors.

The day began around 5am sometimes with a two- or three-mile walk to the farm, and the ag lab was ready to start work an hour later. Some labourers had arrived much earlier, including the cowman and horseman. During lambing, the shepherd would live in the shepherd’s hut to be with his flock – this meant they were often missing from census records because of their remote location.

Most agricultural labourers commenced employment at the age of seven or eight by scaring birds, stone-picking or weeding, progressing to the more skilled jobs on maturity. Many labourers were annually employed and moved on each year, but some stayed on the same farm for many years. Those who were annually employed used hiring fairs to seek new employment. To show their availability they wore an emblem representing their skill, so farmers knew their speciality.

How to research agricultural labourer ancestors

There is no single record that enables us to formulate details of agricultural labourers’ lives, but many informative records help us build the picture. Since most 'ag labs' were only paid when they worked, virtually every family would have regularly claimed relief so Poor Law records and parish charity records provide a wealth of information.

Other useful records include land and estate records, manorial records, trade union records, old maps and records of the law courts. Some agricultural labourers even left wills.

Quarter-session records detail minor offences such as poaching. Old newspapers contain information about meetings of local agricultural trade unions, unrest, bad harvests, medical epidemics, social conditions and other issues which affected a labourer’s life.

Agricultural labourer ancestors: The best websites

1. The Museum of English Rural Life

Founded by the University of Reading in 1951, the Museum of English Rural Life (MERL) houses objects, archives, photographs, film and books, recording changes in the countryside and the lives of agricultural labourers.

The museum’s website is excellent – attractive, easy to use and navigate, with plenty of useful information presented in a visually-stimulating, digestible way.

Most useful for family history purposes is the Collections section, which gives an introduction to MERL’s collections along different themes. You can also search the museum’s catalogue online to find out if it’s worth a visit. The database covers the main MERL collection (library, old photographs, archives and objects) and the Bibliography of British and Irish Rural History.

2. A Web of English History

Beginning life as a student reference tool called Peel Web, this site has grown into a valuable resource on later 18th and early 19th century English history. Despite the somewhat old-fashioned layout, it has useful information and primary resources on lots of political and social events relevant to our agricultural labourer ancestors’ lives, such as the Corn Laws and the Swing Riots.

3. Rural Museums Network

This website provides a map of rural museums and information on aspects of agricultural labourers' work such as beekeeping, dairy-keeping and ploughing.

4. Agriculture and the Labourer

Although concerned mainly with Cambridgeshire and containing some information specific to that county, this is one of the most accessible introductions to the life of an agricultural labourer available online.

In accessible language, it explains the different types of employment, the nature of agricultural work, the tools used, the jobs that were allocated to women and children, community customs, leisure pursuits, the impact of the Napoleonic Wars and the growth of emigration to America and Australia.

6. British Agricultural History Society

Founded in 1952, the BAHS is the next step for those interested in agricultural labourer ancestors, with a twice-yearly periodical, an online forum and a programme of talks.

7. Family and Community Historic Research Society

In the 1830 Swing Riots, agricultural labourers across southern and eastern England destroyed the new farming machinery that they feared would rob them of their livelihoods. The FACHRS have published Swing Unmasked, a 320-page book based on their research into the extent of the riots. It’s on sale for £12 along with a disc containing the names of 3521 agricultural labourers associated with the events.

8. Arley Hall Archives

This site is built around the archives of a Cheshire country estate in the second half of the 18th century. You can explore general account books, as well as material on cheese production, rentals, accounts, corn milling, staff lists and more. The farming section includes records relating to operations and costs in the 1750s and scans of farm account books, ledgers and timesheets of the labourers, with descriptions of work carried out. The ‘Receipted Invoices’ section alone has 6,260 documents. Enter ‘Farmer’ in the ‘Occupation’ category to see lists of names, money spent, goods or services bought, and a scan of the original document. The first is a series of payments made to farmer James Hulme in 1749 for transport around the estate.

9. The Book of the Farm

“The young farmer, left to his own guidance, when beginning to learn his profession, encounters many perplexing difficulties.” That’s more or less the first piece of advice from Henry Stephens’ three-volume work published in 1844, which will tell you more than you could ever need to know about the agricultural working practices of the mid-19th century. This was written as a how-to guide, so describes best practices, working customs and pay. Available for free via Google Books, you can simply read it online or download a text file, a PDF or an EPUB version – the latter optimised for reading on tablets and smartphones.

10. British History Online

The digital library British History Online holds vast quantities of material on ag labs, as a simple keyword search for ‘agricultural labourers’ shows. This can give you access to all sorts of information about how the rural workers in your family tree lived. You can narrow the results by both region and period, and so begin to build up a snapshot of the social and economic conditions of a particular place and time. With a little digging, this can give you real insight into the experiences of an ag lab or yeoman/tenant-farming family. You can discover how they would have been affected by changes to land use, or how they coped with the Great Depression of British Agriculture, which occurred during the late 19th century and was caused by the dramatic fall in grain prices that followed the opening-up of the prairies in the USA. You can find out about the large-scale changes that would have impacted on their lives such as mechanisation, the type of crops that were grown, and the ramifications of shifting from the old open-field system to enclosed fields. There’s a section on rental levels, littered with examples, as well as information on land-tax assessments, demands for housing on farms, and how the coming of the railways affected land usage. Although the website does not detail where to find records, most of the articles have footnotes with which to locate sources that might place your ancestors in their environment.

Agricultural labourer ancestors: Online articles

One of the most fruitful online sources of information on agricultural labourers is academic articles – either posted in full or as downloadable PDFs. Here are four of the best you can read for free, but be warned – they can be rather hard going!

1. The Village Labourer

A digital copy of celebrated work The Village Labourer by J L and Barbara Hammond, originally published in 1911.

2. Farm Servant vs Agricultural Labourer

Farm Servant vs Agricultural Labourer, 1870-1914, by Richard Anthony, examines the socio-economic structure of rural society.

3. Agricultural Labourers

Article on agricultural labourers taken from an 1874 edition of The Cornhill Magazine.

4. Agricultural Revolution in England 1500 – 1850

A more accessible overview of agricultural change in England from 1500 to 1850, by Professor Mark Overton.