Who were the WW2 Wrens?

Only a century ago, it was unthinkable for women to serve in the armed forces but heavy losses at sea during the early years of the First World War prompted the Royal Navy to form the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS). Established in 1917 and popularly known as the ‘Wrens’, it paved the way for the formation of other similar organisations such as the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps and the Women’s Royal Air Force.

If any of those enlisting for the Wrens had ambitions to go to sea, they were soon disappointed. Its motto, ‘Never at Sea’, made it clear that their duties would be entirely on land.

In April 1939, with the threat of another war looming over Europe, the Admiralty decided to re-establish the WRNS, once again with the idea of releasing men for sea-based service. New posters encouraged women to ‘Join the Wrens and free a man for the fleet’. This time the director was Vera Laughton Mathews (1888-1959), who had served with the WRNS during the First World War as a Principal Officer, and had for a while been in charge of the Training Depot at Crystal Palace in London.

By December 1939, more than 3,000 women had enlisted, and this number grew steadily as the war progressed, peaking in 1944 at nearly 75,000 officers and ratings, spread across 50 branches and undertaking around 200 different jobs.

What did the WW2 Wrens do?

Jobs were limited to domestic or office-based duties, but as manpower shortages became acute, the Wrens were deployed to an ever-growing range of vital and often dangerous roles, including those of radio operators, bomb range markers, radar detectors and mechanics.

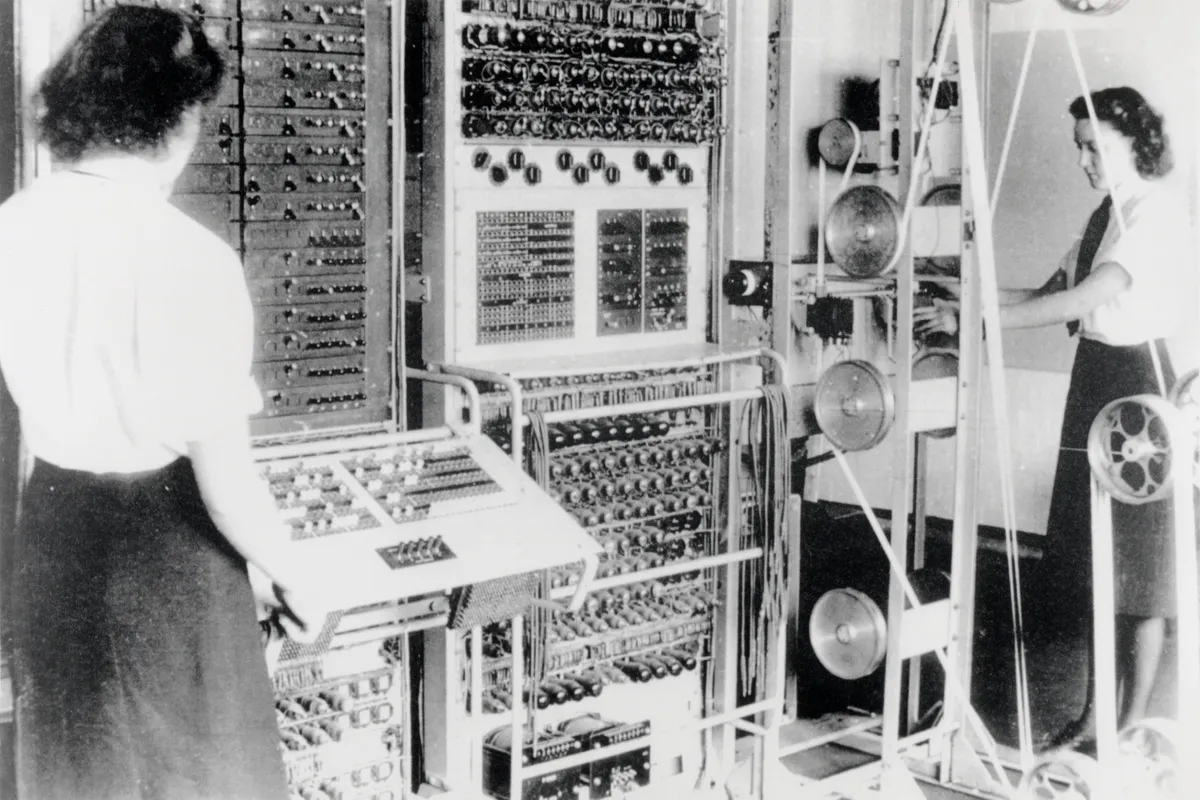

Some Wrens were deployed to coastal stations to intercept naval signals from German U-boats. Others went to Bletchley Park to assist the Enigma code breakers or help staff the Naval Censorship Branch, either in London or in mobile units. Many were posted overseas; by the end of the Second World War, Wrens were stationed at naval bases all over the world, including South Africa, North and East Africa, South America, the United States, North-West Europe, India, Australia, the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean. Overseas postings could last up to two-and-a-half years.

From December 1941, women between the ages of 19 and 30 could be conscripted into the armed forces, with the age limit later rising to 43, while for those who had served in the First World War, the upper age limit was 50. This undoubtedly helped boost the number of recruits applying to the WRNS.

If a woman in your family served in the WRNS, you can trace her record with our guide to Second World War service records

What was life like for the WW2 Wrens?

For many women, joining the WRNS was a harsh and soul-destroying experience. From its earliest days, life as a Wren began with a tough two-week training period, during which the recruits would learn naval terminology and have to undertake menial jobs such as scrubbing floors, cleaning windows and washing up.

The Second World War Experience is an online resource that contains many first-hand stories of Wrens, including Edith Becker, who said of her training period at Westfield: “I really thought they were trying to dispense with my services... I was called upon, with others, of course, to scrub stone corridors, de-clinker the boiler, heave buckets of coal up and down stairs, clean windows in the most inaccessible places... the list was endless. It was a rude awakening. I was just a slip of a girl and barely used to folding my pyjamas!” Another recruit, Jean Gadsden, who trained at Mill Hill, “hated the dreadful place and was overwhelmed by homesickness”.

From this initial period, recruits would go on to be trained for a specific trade, which could last up to six months, depending on the nature and complexity of the job.

Wrens were not subject to the same disciplinary regulations as their male counterparts as they were still technically civilians, but nevertheless a high standard of behaviour was expected. Recruits were not permitted to wear jewellery, hair had to be worn off the collar, and they were not allowed to speak to officers.

Betty Thomson, another recruit included in The Second World War Experience, recalled that “we weren’t allowed to go down the same corridors as the officers in those days”, while Patricia Potton was confined to barracks for seven days for singing “immoral songs” after a night out.

Each naval base was under the charge of a Port Superintendent, who was responsible for recruitment, behaviour and competence. Salaries were meagre, but board and lodging were provided so most Wrens managed a fairly comfortable existence.

Uniforms were also provided. From 1939, all Wrens wore a double-breasted jacket, skirt, tie and white shirt, with different hats according to rank. For Cora Jarman, the uniform was one of the attractions of joining the Wrens: “I would have been compulsorily called up into one of the services when I was 18, so I volunteered to join the WRNS because the uniform had no buttons to clean and was the nicest to my way of thinking.”

During both world wars, the recruitment of women into the naval service was initially resented by their male counterparts, but these feelings mellowed over time as the contribution of the Wrens was noted and appreciated. One senior Royal Navy commander commented: “I did not want WRNS but as I had to have them I made the best of them, and I must say we have been very lucky in our WRNS.”

Relationships between the sexes were subject to strict guidelines. Wrens were permitted to socialise with their male counterparts but were expected to behave in an appropriate way. Most Wrens were able to enjoy active, but largely innocent, social lives.

Despite the WRNS motto ‘Never at sea’, some of the recruits did get a taste of life on board – much to their delight.

In 1943, Lady Rozelle Raynes was one of the first recruits to go on a stoker’s course in Portsmouth, after which time she was drafted to the Southampton-based HMS Tormentor, a Landing Craft Infantry Base, where her duties included delivering stores to the ship and bringing the men ashore each evening.

She wrote of her time there: “It was very cold sometimes in midwinter with the ropes frozen up... you almost needed a hammer to get the ropes off the shore sometimes, but somehow it didn’t matter because it was so wonderful, you know, being on a boat.”

Women were also trained to operate small boats close to the shore, and as the war progressed, were increasingly deployed on troop ships in a variety of roles, from assisting with naval training to becoming coders and cypher officers.

They were also drafted into other branches of the Royal Navy, notably the Fleet Air Arm, where they took over traditional male roles such as those of radio and air mechanics, and flying transport planes. In the summer of 1942, some Wrens were drafted into the Submarine Service as torpedo women and submarine attack teachers.

The most significant sea-based operation involving Wrens was the D-Day landings in Normandy in June 1944, when they took some of the smaller boats across the Channel and helped tow stricken boats back to England.

The growing reliance on women during WW2, and their ever-expanding range of duties, both at sea and on the shore, exposed them to increasing dangers. By the end of the war, more than 300 Wrens had lost their lives, with a further 22 wounded. Demobilisation began shortly after the declaration of peace in the summer of 1945.

The role played by the WRNS had been considerable – a fact highlighted by Vera Laughton Mathews in October 1945 when she told the recruits: “The war is over and you have had a hand in winning it. You have helped to lift this burden of horror and suffering from the world.”

The WRNS remained in existence after the war and was declared a permanent service in February 1949. Around 3,000 Wrens were retained to give administrative support to Royal Navy bases in the UK and overseas.

The idea of integrating the WRNS into the Royal Navy was first mooted during the 1970s, and a major step towards this was taken in 1977 when recruits became subject to the Naval Discipline Act and able to undertake a greater range of trades. In 1981, the WRNS training base HMS Dauntless was closed after 35 years, and women trained alongside their male counterparts at HMS Raleigh. In 1990, women were officially deployed at sea for the first time, when 20 Wren officers served on HMS Brilliant during the Gulf War. Three years later, the WRNS was fully integrated into the Royal Navy. Since then, all female recruits have been able to serve at sea at all levels.

The fact that women are now recognised as being capable of serving alongside men as equals is in no small way due to those pioneering women of the First and Second World Wars, who proved their worth in the face of extreme difficulty and danger.