Everyone has heard of the Spanish Inquisition. Less well known is that tens of thousands of Britons descend from their victims, because Oliver Cromwell invited Sephardic (Iberian) Jews to settle in England in 1656. This includes TV presenter Mark Wright, as he discovered on Who Do You Think You Are?

Who are the Sephardic Jews?

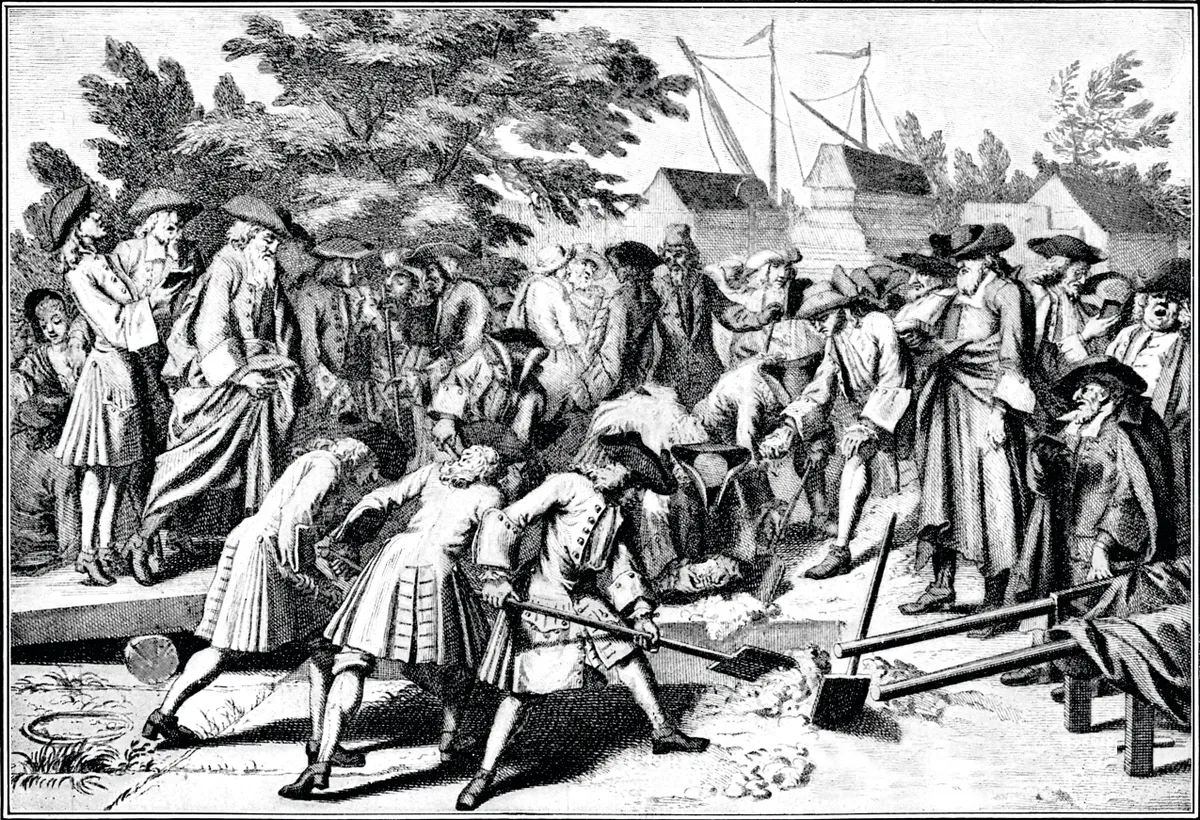

Sephardic Jews is the name for Jewish communities originally from the Iberian Peninsula (modern-day Spain and Portugal). In 1492 Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon issued the Alhambra Decree, banishing Jews from their territories. Sephardic Jews were persecuted by the Spanish Inquisition in the 16th and 17th centuries and many sought refugees overseas, in cities including Livorno in Tuscany, Amsterdam in the Netherlands, Altona near Hamburg and London. Many Sephardic Jews also travelled to colonised countries, and it was not uncommon for someone to be born, married and buried in three different countries, sometimes under three different names.

How to prove Sephardic ancestry

Many people’s starting point in researching Sephardic Jewish ancestry is the discovery of an ancestor with a Spanish or Portuguese (or sometimes Arabic or Hebrew) surname. The ancestor may not have been of Sephardic Jewish origin, but the possibility deserves investigation. The records of the Spanish and Portuguese Jews’ Congregation of London – now rebranded the S&P Sephardi Community – at the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) can only be used with special permission, and most of the records are written in Portuguese. The vital records up to 1900 have been transcribed into the six-volume Bevis Marks Records (Oxford University Press), available at major libraries. However, some of the early birth and circumcision records are missing. A Jewish boy should be circumcised at eight days old. This was also required of adult men arriving in the community from the peninsula. Always keep an eye open for the word vindo, the Portuguese word for ‘arrival’.

Another useful record for tracing Sephardic Jewish ancestry is the ketubah, a marriage contract or prenuptial agreement. It includes the spouses’ and their fathers’ names, is written in Aramaic, and is signed by the groom. The bride and synagogue both receive a copy; the London synagogue copies survive, and can be accessed via volumes two and three of Bevis Marks Records.

Note that when Ashkenazi Jews from Germany and East Europe arrived in England, the Sephardim originally refused to marry them. This began to change in the late 18th century. Generally, a woman would join her husband’s community. The early records simply record these women as Tudescas (Portuguese for ‘Germans’), without stating their names.

In addition, the first action of a new Jewish community is to establish a cemetery. The Velho (Portuguese for ‘old’) off London’s Mile End Road opened in 1657 and functioned until 1733. The burial records were transcribed by RD Barnett in volume six of Miscellanies of the Jewish Historical Society of England (1962). The nearby Novo (Portuguese for ‘new’) cemetery operated between 1733 and 1913. Although much of the cemetery was destroyed in the 1970s, details of burials are in volume four of Bevis Marks Records. Burials in the community’s functioning cemeteries – at Hoop Lane and Edgwarebury in North London – can be consulted on the Hoop Lane Cemetery website. The functioning cemeteries are shared with other Jewish denominations, so check whether the burial is in the Spanish and Portuguese section. Sephardic Jewish gravestones are always flat.

Most members of the congregation were poor, supported by a small number of wealthy families. Perhaps your ancestor benefited? The accounts books (in the archive of the Bevis Marks Synagogue at LMA) have not been transcribed but include information such as the fintas (roughly ‘membership fees’) paid by the wealthy, and the handouts of clothes, coal, money and matzah (unleavened bread for Passover) to the poorer members. Records can be ordered by first name, either alphabetically or by its first mention in the Bible. As well as revealing your Sephardic Jewish ancestor’s social condition, the accounts can establish when they were in London. The mahamad (‘board’) kept detailed records, sometimes including information on legal cases and trade deals.

There is also a database of resources for researching Sephardic Jews and Crypto-Jews (Jews who outwardly lived as Christians to avoid persecution), including searchable lists of names, on the ASF Institute of Jewish Experience website.

Sephardic Jewish records in Amsterdam

When the London paper trail runs cold, it is often worth checking Amsterdam. The Portuguese-Jewish archive of Amsterdam, now in Amsterdam City Library, has mostly been digitised. The Amsterdam records follow the same format as London, but are much larger. As well as the vital records, the Souza Books are worth reviewing. These are records of families, ordered by head of household. Marriages in Amsterdam had to be registered with the civil authorities, and the couple had to state where they were born. This can be the key to unlocking a family’s Iberian history.

Sephardic Jewish records in Spain and Portugal

The first place to look in Spain and Portugal for Sephardic Jewish ancestors are the Inquisition records. Those of Portugal mostly survive, are well indexed, and many files have been scanned and are freely available. Unfortunately, the Spanish records are partially lost and poorly indexed. An Inquisition processo, or trial record, can be anything from a couple of pages to over a thousand, and can provide a treasure trove of information including a prisoner’s appearance, biography, religious knowledge, genealogy, their statements and confessions, and those of others. Also, the prisoner would sign their statements. To find an ancestor in the National Archive of Portugal's collection of digitised processo, try searching for someone's name plus the word judaismo.

Sephardic Jewish surnames

Tracing Sephardic Jewish surnames can be a challenge. In London and Amsterdam someone would use a Hebrew name, while in Spain and Portugal they used a Christian name. Also, in Spain and Portugal people traditionally have two surnames, one from each parent; in Spain the father’s comes first, and in Portugal the mother’s. A surname might be adopted from a grandparent. Spellings can vary between countries. A wife may take her husband’s surname. Some people use a single surname. Others might append a city name to a single surname, and cousins may share the same name. Still, diligent research can overcome these obstacles.

Can a DNA test show that you have Sephardic Jewish ancestors?

Autosomal DNA tests are best for finding more recent connections. Once you have gone back five or six generations, the amount of DNA you will have inherited from a specific ancestor makes it harder to connect it to the Sephardic community of the 18th century and beyond. Having said that, MyHeritage does claim that its DNA test recognises markers that suggest Sephardic ancestry. A more reliable test would be a Y-DNA test as this stays relatively unchanged from one male to the next. FamilyTreeDNA has two Sephardic groups, one for people with proven Sephardic ancestry and another for those who believe that they have Sephardic ancestry but where the family later converted.

For more support with researching Sephardic ancestors why not join The Sephardic Diaspora Facebook Group or for professional assistance contact David Mendoza via his website.