Many family historians with Irish ancestry who encounter difficulties locating relevant records attribute their lack of success to the fact that “everything was burned in the fire”. This ubiquitous statement refers to the burning of the Record Treasury building of the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI) in late June 1922. This event, which can still elicit tears and rage from archivists, historians and genealogists, was responsible for the destruction of a very significant collection of records. However, not all genealogical records were held in the PROI, and not all of the collections in the PROI were entirely destroyed.

The destruction of the PROI was the first action of the Irish Civil War, the culmination of a decades-long campaign for home rule and, latterly, independence from British rule. The Irish War of Independence (1919–1921) brought the British government to the negotiating table. The December 1921 talks between British and Irish leaders concluded with the Anglo-Irish Treaty, an agreement for self-government for Ireland. However, the treaty contained clauses, such as an oath of allegiance for members of Parliament and the partition of Ireland, that were unacceptable to many who had spent the previous decade fighting for a republic.

Although the treaty was ratified, the country was divided and Ireland descended into civil war. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) split between supporters of the treaty who became the army of the newly created Irish Free State and those opposed to the treaty.

Under IRA control

In mid-April 1922 the anti-treaty IRA under Rory O’Connor, in search of a garrison in Dublin, occupied the Four Courts complex. The complex, located in the heart of the city on the banks of the River Liffey, included the Record Treasury building of the PROI, the repository for the historical records documenting the governing and administration of Ireland from the 13th century onwards.

The anti-treaty forces fortified the complex with barbed wire and sandbags, blocking the windows with furniture and leather-bound volumes (some surviving volumes are shot through with bullet holes). O’Connor’s forces also brought gallons of petrol into the complex for fuelling vehicles, and set up their own munitions factory.

It was not until late June that events forced the hand of the Irish government to oust the anti-treaty forces. During this conflagration a large explosion showered the city with fragments of legal papers. Flaming debris from the explosion appears to have started fires in the Record Treasury building, causing the famous tragedy.

The PROI’s holdings were vast and wide-ranging. Established by an Act of Parliament in 1867, the office gathered record collections from state repositories, courts and commissions under one roof in a purpose-built structure in the Four Courts complex. The PROI consisted of the Record House, with a public reading room, strongroom, library, offices and accommodations, and the Record Treasury, a large open-plan building that housed the collections. State records that were 20 years old or more were transferred, annually, to the PROI, along with historical collections.

Of course, many of the collections that were deposited at the PROI were of major significance for family historians. Following the disestablishment of the Church of Ireland in 1869, each parish was required to deposit their baptismal, marriage and burial registers with the PROI. Opposition to this legislated requirement forced an amendment that allowed a parish to retain its records, provided they could be kept secure. Thus, about half of the Church of Ireland registers were deposited in the PROI and largely lost in 1922.

Fortunately, the Roman Catholic Church did not fall under this legislation so its registers remained in local custody. Similarly, the records for the civil registration of births, marriages and deaths were not part of the PROI collection, and they survive fully intact.

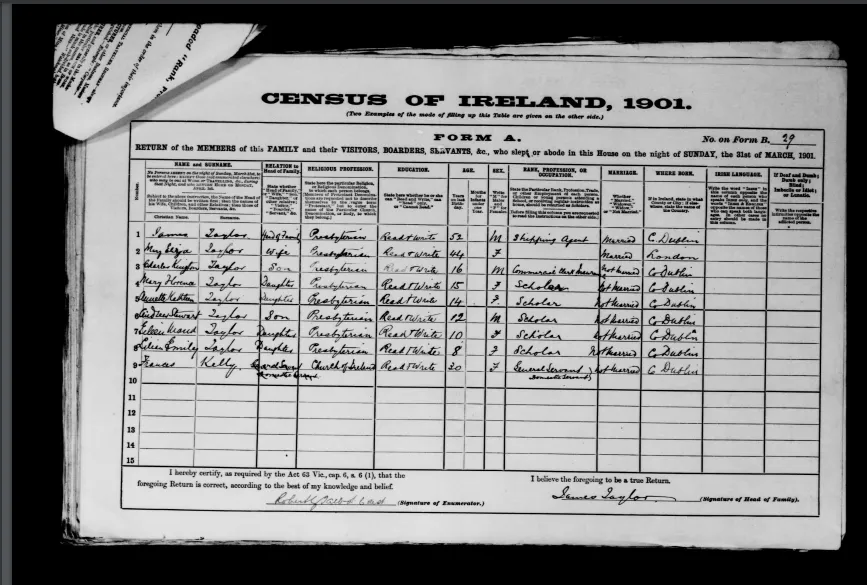

Another vital component of the PROI were census returns. The earliest Irish state census dates from 1821, and was repeated every decade thereafter until 1911. The returns for 1821–1851 were deposited with the PROI. In fact, the 1841 and 1851 returns were used in the early 20th century to verify the age of applicants for a state pension who could not produce a birth certificate. These application forms, marked with notes taken from the early returns, today act as a very limited substitute for some of what was destroyed.

Accidental destruction

The returns for 1821–1851 were destroyed in the fire. The returns for 1861–1891 are believed to have been mistakenly destroyed by a government order prior to 1922. So the only complete surviving census returns for Ireland date from 1901 and 1911.

There is a story passed down by genealogists that the day before the PROI was occupied a genealogist, possibly Philip Crosslé, had been searching the 1841 census for the parish of Killashandra in County Cavan. The returns, which he intended to access again the following day, were put in the safe in the Record Building, rather than being returned to the Record Treasury, and thus escaped damage. There are also fragments of early returns that were copied before destruction, including a number of Cavan parishes for 1821 and parts of Derry for 1831.

The PROI also held records of the Irish courts, wills and administrations from the principal and district registries, and the records of the clerks of Crown and Peace, which included criminal and civil administrative papers for every Irish county. Historical records pertaining to the ownership and transfer of land, including deeds and rolls, some of which dated from the 13th and 14th century, were also partly destroyed. However, the records of the Registry of Deeds, recording deeds and conveyances representing transfers of property in Ireland, were lodged in a different purpose-built repository in the King’s Inns complex and were never moved to the PROI. They remain entirely intact.

The destruction of the 19th century census returns and court records has had a huge impact on family history research of the entire population of Ireland, the majority of whom were Roman Catholic and of the labouring or small tenant farmer class. Even the destruction of Church of Ireland parish registers and wills and testamentary records affects more than just the descendants of the landed gentry. The Church was not exclusively the church of the landowning class; a large component of this denomination were labourers, tradesmen and farmers, like their Catholic neighbours. Similarly, although the majority of wills and administrations that were destroyed pertained to Protestant property owners, there were certainly Catholic merchants and land owners who left wills or estates to be administered.

A devastating loss

The 1922 destruction of the PROI is an ever-present, gaping hole in the road for Irish genealogists, who have spent the last 100 years searching for documents that can be used as substitutes for what was destroyed. The notes and notebooks of genealogists past, whose work prior to 1922 includes copies of records since destroyed, have been elevated to a quasi primary source, replacing lost census returns, wills and parish registers. Tax and land-valuation records have been marshalled into prominence as census and will substitutes.

During the recent decade of centenaries a project called Beyond 2022 was established at Trinity College, Dublin. The purpose of Beyond 2022 is to build a virtual Record Treasury to be populated with digital, searchable copies of records that survived the fire, alongside copies and substitutes that replace some of the lost collections. This free online digital repository launched on 27 June 2022, 100 years after the Record Treasury was destroyed.

Using the lists and guides to collections published by the PROI prior to 1922, project researchers have spent years trawling through archives and libraries trying to locate copies of items that had been destroyed. Many local and national libraries, archives, repositories and historical and genealogical societies have partnered with Beyond 2022 including the library of Trinity College Dublin; the National Archives of Ireland; The National Archives at Kew; the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI); the US Library of Congress; the Bodleian Library of the University of Oxford; and National Records of Scotland.

While many of the records destroyed were unique, surviving copies and extracts created by genealogists before 1922 will eventually make their way into the virtual Record Treasury.

In addition the Victorian and pre-Victorian employment of armies of clerks who copied administrative records means that there are some duplicates of the destroyed originals deposited in other archives. Historians and antiquarians also created copies or transcripts of manuscripts, and since 1922 academics and researchers have been ferreting out substitutes for what was lost. The Irish Manuscripts Commission (IMC), a public body founded in 1928, has spent over 90 years publishing editions of such primary sources. A digital collection of the commission’s publications has already been deposited with Beyond 2022.

Significant sources

Major sources for family history will appear in the virtual Record Treasury. For example, the surviving returns and transcripts of an island-wide religious census of 1766 have been entirely digitised and will be fully searchable online for the first time. The original surviving returns from the PROI will be published alongside transcripts or copies from the Genealogical Office (the National Library of Ireland), PRONI, Trinity College and the Representative Church Body Library, the official archive for the Church of Ireland. The census for some parishes recorded the name of the head of household and the number of each religion in their household. Other returns recorded only the numbers of Protestants and Catholics in each parish. Even with found copies, the collection is not complete for the country.

Another important source is the Quit Rent Office copy of the Books of Survey and Distribution. Compiled in the late 17th century, the books document owners of Irish lands prior to the 1640s, and to whom their lands were granted after confiscation – most Catholics’ land was regranted to families, soldiers or investors who supported the 17th-century British military campaigns in Ireland. These records can help you establish when an English or Scottish family might have settled a particular Irish estate.

Beyond 2022 does not mean that the entire census returns from the early 19th century will be reconstituted, or that lost Church of Ireland registers will be restored. However, it is likely that once the Representative Church Body Library’s project to digitise its collection of Church of Ireland registers is complete, they will appear in the virtual Record Treasury, alongside transcripts and copies of lost registers found in other repositories like PRONI and Trinity College. We can also look forward to the digitisation of the Crown and Peace collection, which includes 19th-century ejectment books recording cases for eviction taken against tenants.

The Beyond 2022 project has seen historians, archivists and conservators from around the world exploit new technology to bring old, sometimes forgotten or even lost manuscripts together to recreate, as much as possible, PROI’s original collection. Coming at the end of Ireland’s decade of centenaries, this project will leave a legacy, not of frustration and muttered curses for Rory O’Connor and his men, but one of collaboration and restoration.