If you’ve researched your family history, you’ll have found the baptism, marriage and burial records kept by local parishes invaluable for tracing milestones in your ancestors’ lives. But parishes kept many other records besides these familiar building-blocks.

Every parish church used to hold its records, including registers of baptisms, marriages and burials, in a wooden chest. These therefore became known as parish chest records. In addition to the registers, the records collections could include minutes of meetings held by parish officials; rate books; accounts; maps; charity deeds; church seating plans; settlement and bastardy papers; and apprenticeship indentures.

The parish, supervised by local justices of the peace, was the centre of local government, and meetings to discuss every aspect of community life were held regularly in a room in the church called the vestry, where the vestments – the clergy and choir’s robes – were also kept. In time, the meeting itself became known as the vestry and the minutes produced were called vestry minutes. One of the chief duties of the vestry was to assess, levy and administer church and parish rates, which were based on the value of property. The income and expenditure from these parish funds was often presented in the form of accounts.

During vestry meetings, parish officers were elected on an annual basis. Every responsible householder was expected to take their turn as a parish officer, although some paid a fee to exempt them from their obligations. Churchwardens, who were charged with looking after church affairs, and parish overseers, whose job it was to take care of the poor, were two of the most important positions. Other elected officials that often feature in the parish records include the constable, who kept law and order; the sexton, who was responsible for the upkeep of the churchyard; the waywarden or surveyor, who maintained the roads and bridges; and the parish clerk, who assisted the incumbent and kept the parish records. In smaller parishes, it was customary for some roles to be combined.

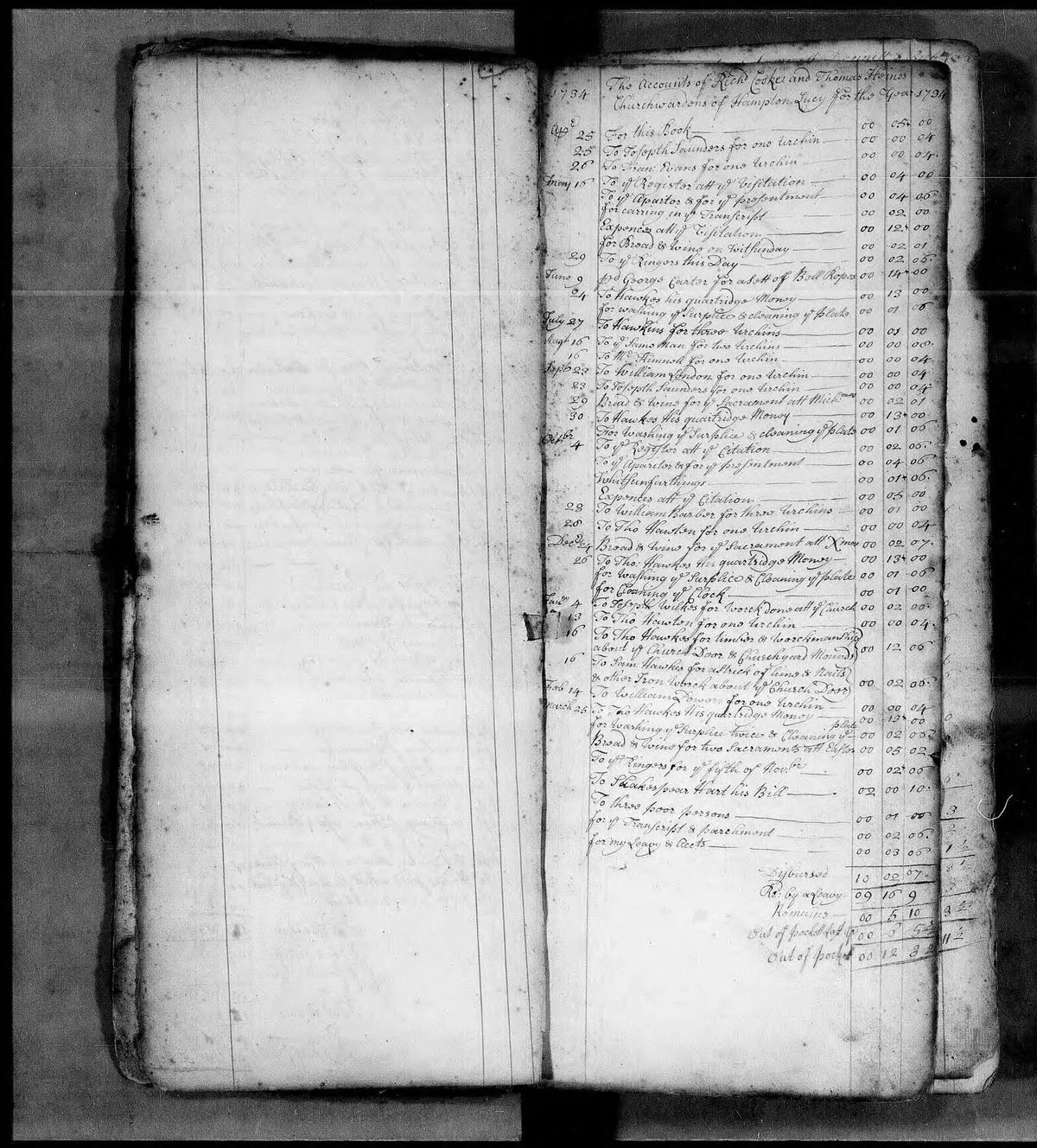

Parishes had at least two churchwardens and it was their responsibility to administer church funds, which were obtained from church rates, almsgiving, or revenue gained from land or animals. These funds were used to maintain the church fabric, the vestments and plate, and for the provision of bread and wine for communion. The churchwardens also presented those accused of breaking ecclesiastical rules to the archdeacon’s court during a visitation. Their accounts give an insight into the central role of the church in the community and often mention tradespeople, as well as those paid for catching vermin in the parish.

Records of the poor

After the 1601 Poor Law Act, parish rates were focused on the care of the poor. This was the primary concern of most vestries, although funds also had to be spent on highways and other statutory obligations. The money collected was distributed by the parish overseers, an office dating from 1572. Lists of monetary payments to needy parishioners who were sick, unemployed or in their old age are recorded in the vestry minutes, or the separate overseers’ accounts in larger parishes. Also listed are payments to those who supplied practical assistance such as housing, clothing or medicine to those in need. Able-bodied paupers who were paid for their labour around the parish may also be mentioned. Poor children, particularly orphans or those who were illegitimate, can be recorded in apprenticeship indentures, as once they were apprenticed in another parish, they would no longer require financial support.

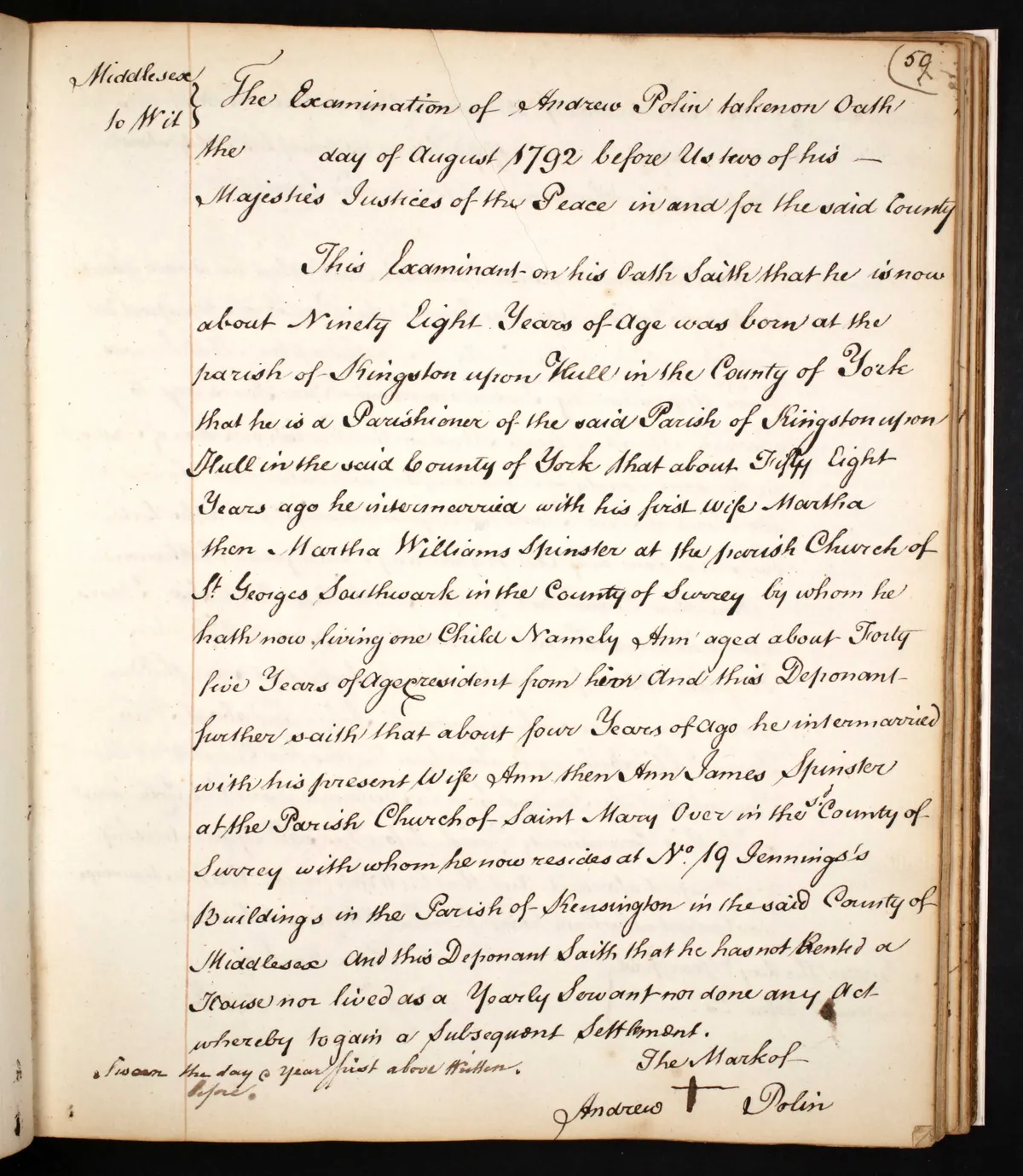

Various pieces of Poor Law legislation established that a person only had the right to poor relief in their place of settlement, which could be gained by residing in a parish for 40 days. According to the 1662 Poor Relief Act, a person could be forcibly removed back to their place of settlement unless they rented a house with an annual value of at least £10, or could prove that they would not become chargeable if they had resided in the parish for less than 40 days. This ensured that each parish was only responsible for its own, because wealthier parishes could be a magnet for the poor. It was the constable’s job to remove those that did not have settlement to the parish boundary. Persons removed may appear in his accounts if they were kept separately, as well as being documented in removal orders. Before being removed, potential claimants were first examined by two justices of the peace to establish their place of settlement. Testimonies given in these settlement examinations can provide a potted biography of a person’s life and history.

Subsequently, there were some alterations to the rules around settlement. In 1685, it could only be given once a person’s presence had been notified to the parish authorities. From 1691, paying the parish rate, serving as a parish officer, working as a servant in the parish for one year, or being apprenticed in the parish provided additional means of obtaining settlement. Women gained settlement if they married a man of the parish, while children aged under seven years old gained their father’s place of settlement.

An Act of 1696 also allowed families to move to a new parish if they had a certificate from their parish of settlement, which accepted responsibility for them. These certificates are sometimes preserved in the parish chest. Following the 1795 Poor Removal Act, paupers could not be removed unless they actually required relief. Among the records there may well be correspondence between parishes, particularly if there was a dispute over a person’s place of settlement.

The cost of maintaining an illegitimate child could be a significant financial burden on parishes. From 1697, it was the responsibility of the parish where the child was born, regardless of where the mother (or father) had settlement. This resulted in heavily pregnant single women being harried from one parish to the next by constables. From 1743, the child had to take the mother’s settlement but if the parents could be persuaded to marry, the mother and child would be settled in the father’s parish. After 1732/1733, a woman who was pregnant with an illegitimate child was legally required to name the father and undergo a bastardy examination. Once the identity of the reputed father was known, a bastardy warrant would be issued to apprehend him. He would be required to appear before the local justices of the peace so that financial support could be agreed. This would be detailed in a bastardy order, and a bastardy bond would then be signed by the father. Occasionally, another relative would agree to pay the money on the father’s behalf. Bastardy examinations, warrants, orders and bonds can therefore provide crucial information about illegitimate children.

Where can you find parish chest records?

Some parish chest records have now been digitised by family history websites. Ancestry has browsable collections of parish records for Dorset and Warwickshire, plus indexes for the parish of Kensington, Middlesex. Findmypast has parish chest records from Plymouth and West Devon. Parish chest records that are not online are available in local archives. You can search the catalogues of local archive services on Discovery, The National Archives’ search engine. Regional family history societies may also have published indexes of parish chest records.