Researching Scottish ancestry differs from researching ancestry in other parts of Britain in several key respects. For centuries, Scotland has had a different administrative and record keeping system to England and Wales, meaning there are a different set of records for researching Scottish ancestry.

Scottish ancestry: Civil registration records

Civil registration in Scotland wasn’t introduced until 1855. Births, marriages and deaths are key records in tracing Scottish ancestry, and your first step should be to search for the right records for your ancestors. You can search all birth records that are over 100 years old, marriage records over 75 and death records over 50 on the ScotlandsPeople government website, although you have to purchase credits to access the records.

You can also search all Scottish ancestry records at the ScotlandsPeople Centre in Edinburgh. The centre charges a day search fee that covers all the records accessed during your visit so offers better value if you want the freedom to access numerous records at once. There are also a number of other centres in Scotland that provide similar access:

- Burns Monument Centre in Kilmarnock

- Clackmannanshire Family History Centre in Alloa

- Heritage Hub in Hawick

- Highland Archives Service Family History Room in Inverness

- Mitchell Library in Glasgow

Birth records are extremely helpful in tracing Scottish ancestry because as well as providing the child’s name, sex and date and place of birth, they include the date and location of their parents’ marriage, making it possible to take your family tree back a generation.

Unlike in the rest of the UK, parental consent was never required for minors (people under 21) to marry in Scotland, which is one reason why so many young English couples flocked over the border to marry at places such as Gretna Green.

Another difference is that civil marriage, performed by a registrar as the celebrant, started in England and Wales in 1837, but not in Scotland until 1940. This was because Scotland legally provided for ‘irregular marriages’ until 1939 – usually by ‘declaration’, where two spouses declared their intent to marry before witnesses, without a celebrant. In such a case you will see the words ‘by warrant of the sheriff substitute’ in the left-hand column of the record, as state permission was required to register such an event. The records will also note details about the couple’s fathers and mothers.

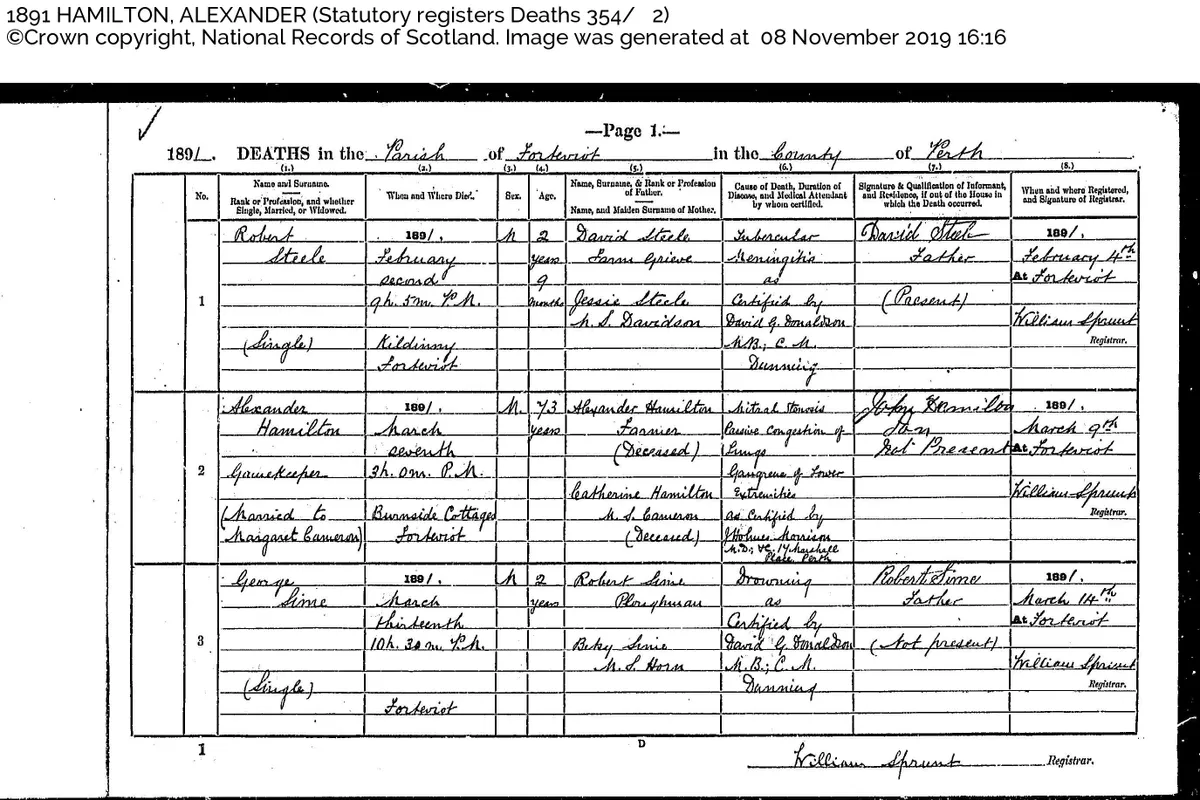

Death records are useful for tracing Scottish ancestry because they contain more details than English and Welsh records. Death certificates name all known former spouses, where and when death occurred, as well as the cause, and also the names of both parents. However, one thing to bear in mind is that these records were filled in after the person died, and the informant may not have the correct information.

Scottish ancestry: Church records

Before 1855, the only records of milestone events in your Scottish ancestors’ lives are baptism, banns, marriage and burial records from the registers of their local church. ScotlandsPeople has digitised records for the Church of Scotland and some Catholic and nonconformist churches. You may also be able to find the registers in a local archive. You can search for these on the Scottish Archive Network Catalogue or using my book, Discover Scottish Church Records.

You can also find a database of Scottish burial grounds on the Scottish Association of Family History Societies’ website, which will help you find where your ancestors are buried. There are also good collections of Scottish Old Parish Registers and Scottish Catholic records on Findmypast.

It’s also worth noting that FamilySearch has free indexes of church and civil birth records from 1564 to 1950 and marriage records from 1561 to 1910, enabling you to trace your Scottish ancestry for free.

The Scottish church or kirk played an important part in the lives of its parishioners beyond just marking births, marriages and burials. Kirk sessions were held to keep the congregation in check, policing moral and local matters. These have now been digitised making them much more accessible.

The church also played an important role in support of the poor up until 1845 when the state took over. Scottish poor records both pre and post 1845 can really shine a light on the lives of your more unfortunate ancestors. Some have been indexed, for example a selection for Dundee and the Highlands can be found on Findmypast.

Scottish ancestry: Census records

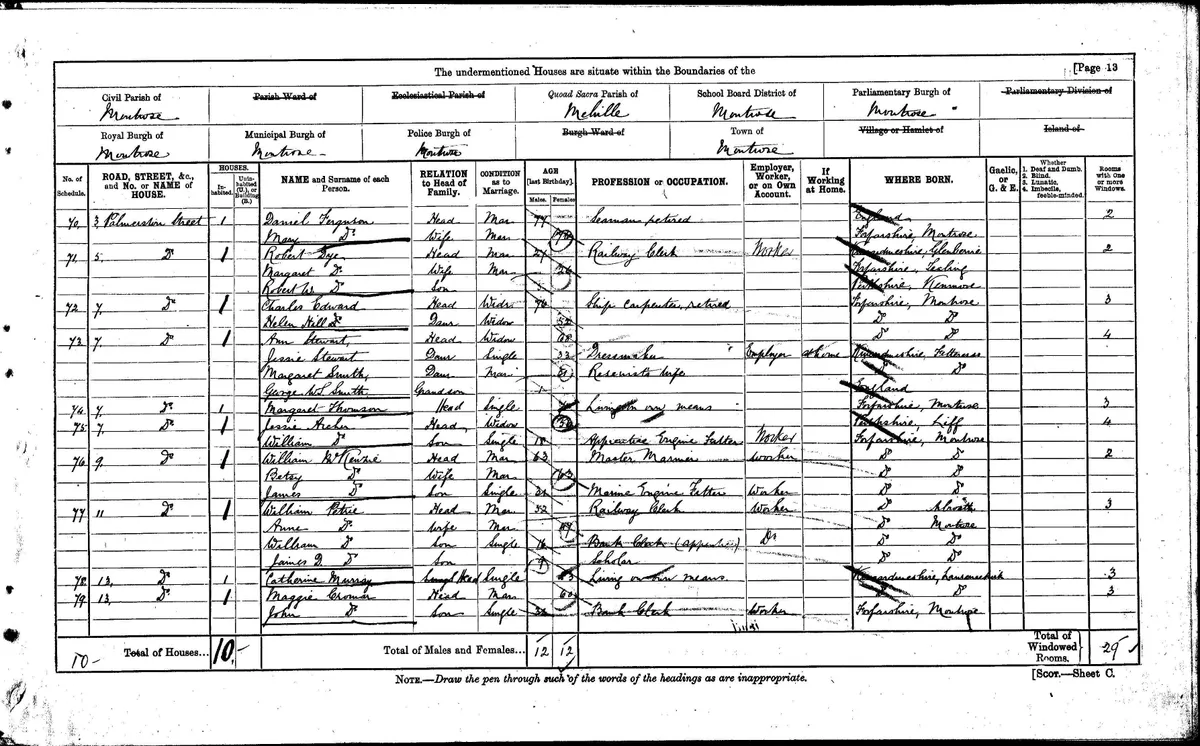

Scotland's census records from 1841 to 1921 are publicly available. Differences included questions about whether inhabitants spoke Gaelic in 1881 and there were also questions about rooms with windows and whether children were being educated at school that reflected Scottish concerns.

The full records are available to search on ScotlandsPeople. Incomplete transcripts from 1841-1901 are also available on both Ancestry and Findmypast. Note that in Scotland women never officially lost their maiden surname after marriage – as such, when widowed, you may find a woman reverting to her maiden name, rather than continue with her married surname.

For those with ancestors from the Orkney Islands there is a rare collection of census records from 1821 that can be freely viewed on Findmypast.

Scottish ancestry: Wills

In Scotland, there were two types of property left behind after death – moveable and heritable. Moveable estate comprised assets that were essentially not land or buildings. Up to the early 19th century certain relatives were automatically entitled to part of this estate, after it was divided into three – the ‘widow’s part’, the ‘bairns’ part’, and the ‘deid’s part’.

A probate record would express how the deceased wanted the ‘deid’s part’ to be bequeathed through the ‘confirmation’ process (known in the rest of the UK as ‘probate’). ScotlandsPeople hosts these confirmed testaments from 1513 to 1925, which note who the court appointed as executors to administer the process, whether a will was left or not.

As the eldest son was usually entitled to inherit the heritable estate, ie, land and property (according to the law of primogeniture), he will usually not be named in these ScotlandsPeople testaments. The records for pursuing the inheritance of heritable estate are called ‘retours’, and are held at the National Records of Scotland.