Who was Charles Booth?

Born in Liverpool in 1840, Charles Booth became a successful businessman, with interests in the leather and shipping industries. For most of his life he was very concerned with the plight of the Victorian urban poor. In 1886, he began an ambitious project to survey the living and working conditions of Londoners. This phenomenal task was to take him and his investigators 17 years to complete.

How did Charles Booth conduct his poverty survey?

Charles Booth's poverty survey focused on three areas: poverty, industry and religious influences. Charles Booth began by obtaining reports from ‘School Board Visitors’, who were responsible for conducting house-to-house visits to gather detailed information about poverty levels and types of occupation among families, and record their children’s school attendance.

The industry angle investigated trades, from tailoring and woodworking to organ-grinding and chorus-line dancing, to establish wage levels and conditions of employment. About 1,000 interviews were conducted with business owners, workers and trade union officials, and a similar number of questionnaires completed by employers and workers’ representatives. The survey also gathered information on the “unoccupied classes” and the inmates of institutions such as workhouses.

Investigators tasked with gathering information on religion interviewed 1,500 clergymen of different denominations, and a further 200 questionnaires were completed by nonconformist and Church of England officials. Charles Booth's inquiry also sought to identify other social and moral influences on peoples’ lives, such as policing, philanthropy and local government.

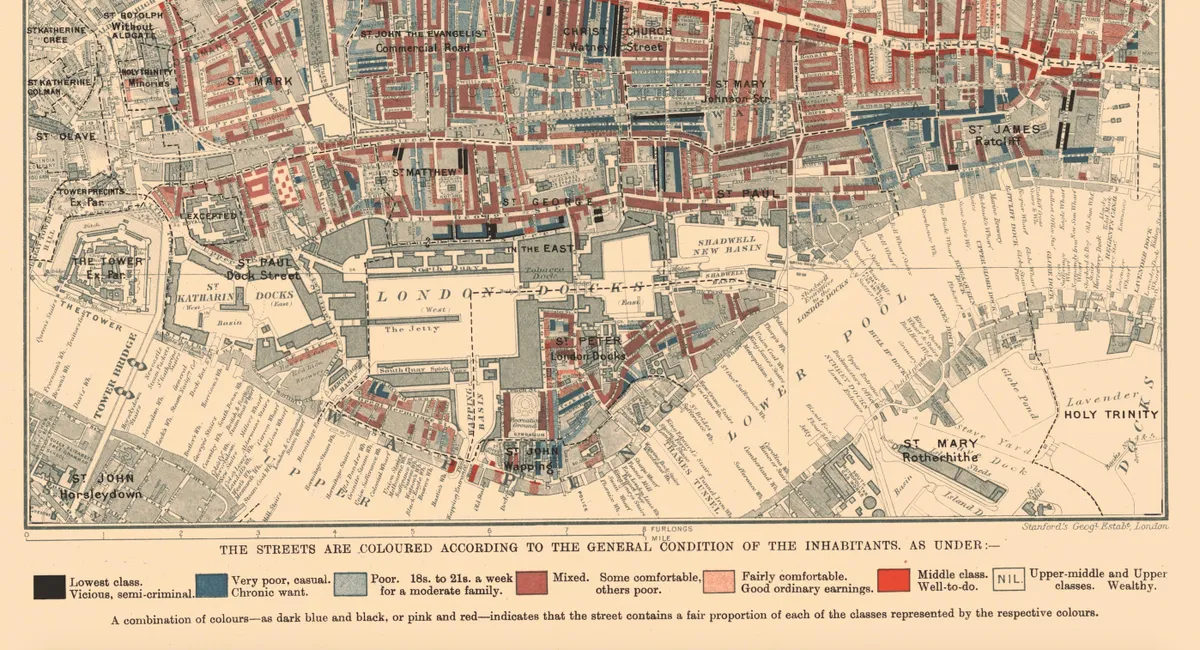

What are Charles Booth's London poverty maps?

The most useful result of the survey for historians is Charles Booth’s old maps showing poverty levels in London. Along with the accompanying maps, they are available to view on the London School of Economics website.

There are two editions of Charles Booth's poverty maps maps. The first, published in 1889, was based on the information gathered by the School Board Visitors. The second, comprising 12 sheets known collectively as the Map Descriptive of London Poverty 1898–9, was based on the observations of the investigators as they accompanied policemen on their beats, and published in 1902–1903.

The online archive includes the second series of the maps. In this pioneering example of social cartography, each street is coloured to indicate the income and social class of its inhabitants. Seven classes are identified ranging from the “Lowest class. Vicious, semi-criminal’ through “Poor. 18s. to 21s. a week for a moderate family” to “Upper-middle and upper classes. Wealthy”. Charles Booth's poverty maps are searchable by street, parish and area, and can be compared with modern maps of London.

Visitors to the Charles Booth's London website can also search a catalogue of notebooks, which includes detailed descriptions of individual pages containing the observations of the investigators as they walked London’s streets between 1897 and 1901.

Some of the Charles Booth notebooks have been digitised and these are grouped into police notebooks, which contain descriptions and features of London streets, their inhabitants and the industry that took place there; Stepney Union casebooks, recording case histories of inmates of Bromley and Stepney workhouses; and Jewish notebooks, which throw light on the work and religious life of London’s Jewish community of the 1880s and 1890s.

George H Duckworth’s police notebook of 1897 (BOOTH/B/346) includes an account of smoking in an opium den in Jamaica Street, Limehouse, kept by the Hindu cook Mr Khodonabaksch, while Beale Road in south Hackney is identified as a “hotbed of socialists”, brothels abound in Bromley’s Back Alley and rats are rife in the drains near a fat refinery in Hawgood Street. The places mentioned in the notebooks are often linked to their location on the relevant poverty map.