The new union workhouses established by the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act typically had a small number of rooms designated as sick wards, but the provision of a separate, dedicated workhouse infirmary (then the usual word for a hospital) was relatively uncommon at that time.

In the mid-1860s, a campaign to improve the often abysmal medical provision in London’s workhouses resulted in the 1867 Metropolitan Poor Act. The Act aimed to remove all sick paupers from the city’s workhouses into a set of large new hospitals known as District Sick Asylums. However, after only two of these, the Poplar and Stepney Asylum and the Central London Asylum, had been established, the cost of completing the scheme became prohibitive.

Instead, the capital’s workhouse authorities were instructed to provide separate workhouse infirmary accommodation for their sick inmates, preferably on a site away from the workhouse. If the infirmary had to be on the main workhouse site, it should be separately managed.

In the decades that followed, many new workhouse infirmaries were established both in London and around the rest of the country. Some were new buildings, while others redeployed existing premises such as the City of London Union’s workhouse on Bow Road, which became the union’s infirmary in 1869. Relatively few provincial workhouse infirmaries were on separate sites; notable exceptions included those at Croydon, Halifax, Leicester, Salford and Stockport.

The 1867 Act also led to the formation of the Metropolitan Asylums Board (MAB). It took over the provision of care for London paupers who were intellectually impaired — those labelled ‘idiots’ and ‘imbeciles’ — or who were suffering from infectious diseases such as smallpox, diphtheria and scarlet fever. The MAB eventually operated more than 40 hospitals and other institutions for the poor.

By the late 1870s, London’s workhouse infirmaries and the MAB’s institutions were increasingly admitting non-paupers for treatment. This practice also became widespread outside the capital, some establishments even taking in paying private patients. In many places, the workhouse infirmary became the local hospital for anyone unable to afford to pay for medical care, a principle that underpinned the National Health Service. The NHS was inaugurated in 1948, and many of its initial facilities were former workhouse sites.

How to find surviving workhouse infirmary records

Almost all of the surviving records that relate to inmates of workhouse infirmaries come from the post-1867 period. The majority of these are for infirmaries on a site away from their parent workhouse, or under separate management at the same location. As with other workhouse records, they are generally found in the relevant county or local record office. A useful finding aid is The National Archives’ online catalogue Discovery.

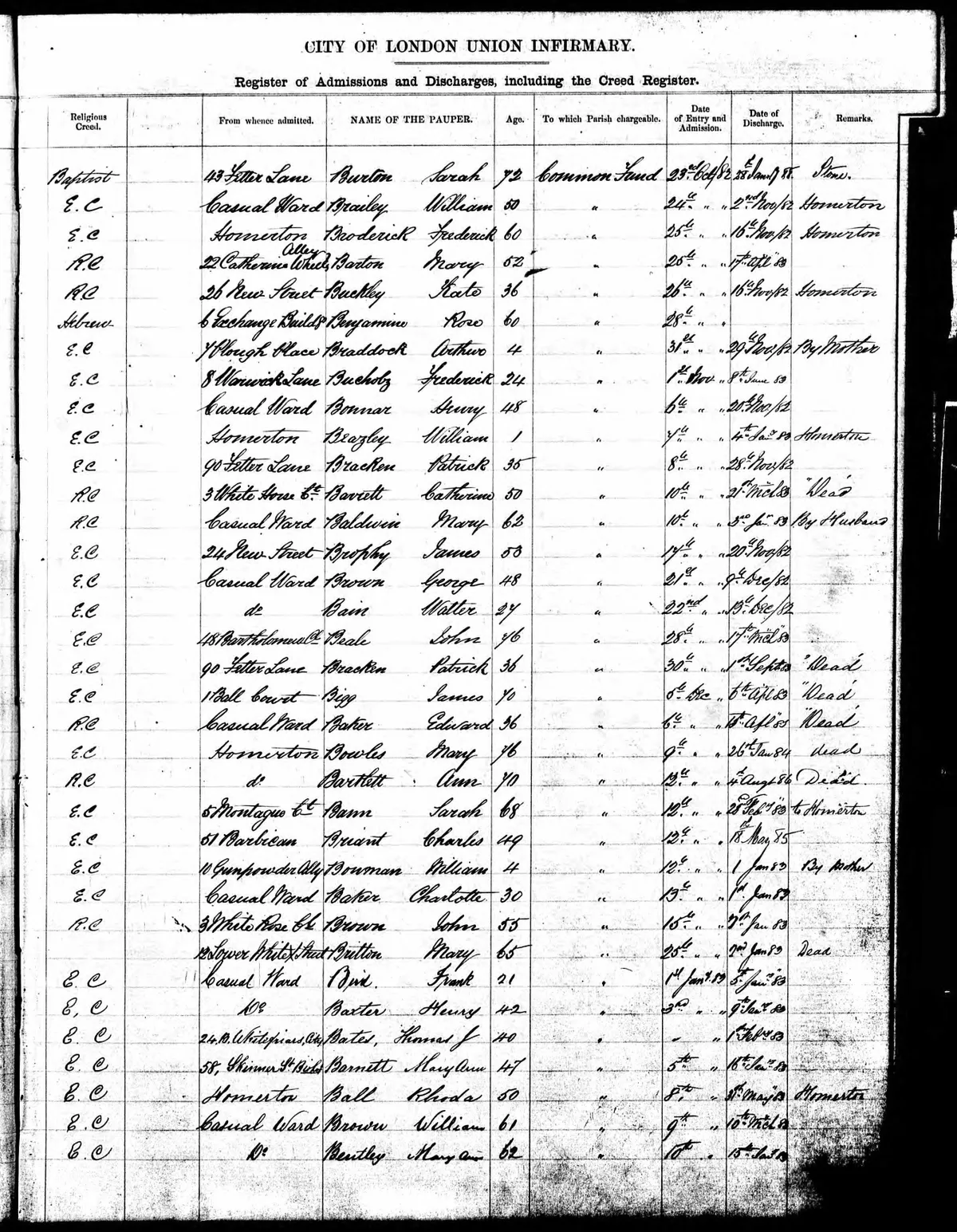

A collection of admission records from workhouse infirmaries in London is held by the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) and available on Ancestry in the collection ‘London, England, Poor Law Hospital Admissions and Discharges, 1842–1918’ . LMA also holds records for the institutions run by the MAB.

Infirmary admission and discharge registers provide a valuable supplement to a workhouse’s own admission records, particularly if they include individuals who were not already workhouse inmates. Their format varies but generally includes each patient’s name, admission and discharge dates, and religious affiliation. Other items may include the person’s occupation, medical condition and previous address – something that can give a valuable link to other records. If this was a workhouse, there should be a corresponding entry for it on the same date in the workhouse’s discharge register. If a private address is given, it may provide a connection to a census entry or other records. A “Remarks” column is often included and may include useful information relating to the person’s departure, such as the fact that they had died, been collected by a particular family member, or transferred to the workhouse or another institution such as an asylum. Transfers to other establishments, such as an MAB fever hospital, may also be recorded in separate registers.

Separately located or managed workhouse infirmaries also kept their own registers of births, deaths and religious creeds. As well as patients’ names and dates, the latter may include previous address and details of the next of kin.

The weekly progress of each patient in the infirmary or sick wards was recorded in Workhouse Medical Relief Books. These typically give each patient’s name, age, dates of admission and discharge/death, their diet, and any ‘extras’ ordered by the medical officer such as brandy or tobacco. Ancestry has examples in the collection ‘Bedfordshire, England, Workhouse and Poor Law Records, 1835–1914’.

Registers of sickness and mortality can be found for Liverpool's workhouse as well as admission and discharge registers for Sefton General Hospital (Toxteth Park Workhouse) and Mill Road Hospital on Findmypast.

You can also find details of more than 2,800 hospitals, including former names, dates of operation and the location of any surviving records using the Hospital Records Database. Although no longer updated, it is still a useful resource. Another useful online resource is Workhouses.org.uk which contains information about every aspect of the workhouse, including medical care and the MAB, plans, photos and details of surviving records.