You’ve been researching your family history for a while, you have notes and files, you have copies of documents and an unwieldy family tree. This is a sign that it is time to pause researching and write your family history, making sure that your family research is collated and preserved for the future in an interesting way.

When you set out to write a family history, you will discover that databases and scattered notes aren’t what captivates your audience; it is the stories that grab their attention. Maybe your family’s story doesn’t seem to have a wider appeal. You have ancestors who were born, got married, had children (not always in that order) and died; that is hardly going to be enthralling for anyone but the hardened genealogist. Here are ways to add the context that will make your family story interesting.

Take a look at the social history of the time: find out what life was actually like for your ancestor. Write about their home. You may not have an exact address, but you can describe the typical housing for someone of their social status in their town. You can also think about the furniture that might have been in that home. Move on to what they would have worn. When writing about clothes, add details of how they were made and laundered. Then there is food. Explain what they would have eaten, and how it was prepared, cooked and stored.

The history of medicine is another aspect that you might consider. This could be appealing to younger relations, who tend to have a fascination with the gory bits. All of our ancestors except the most recent ones are dead, so what did they die of? What were the symptoms and treatment for that condition at the time?

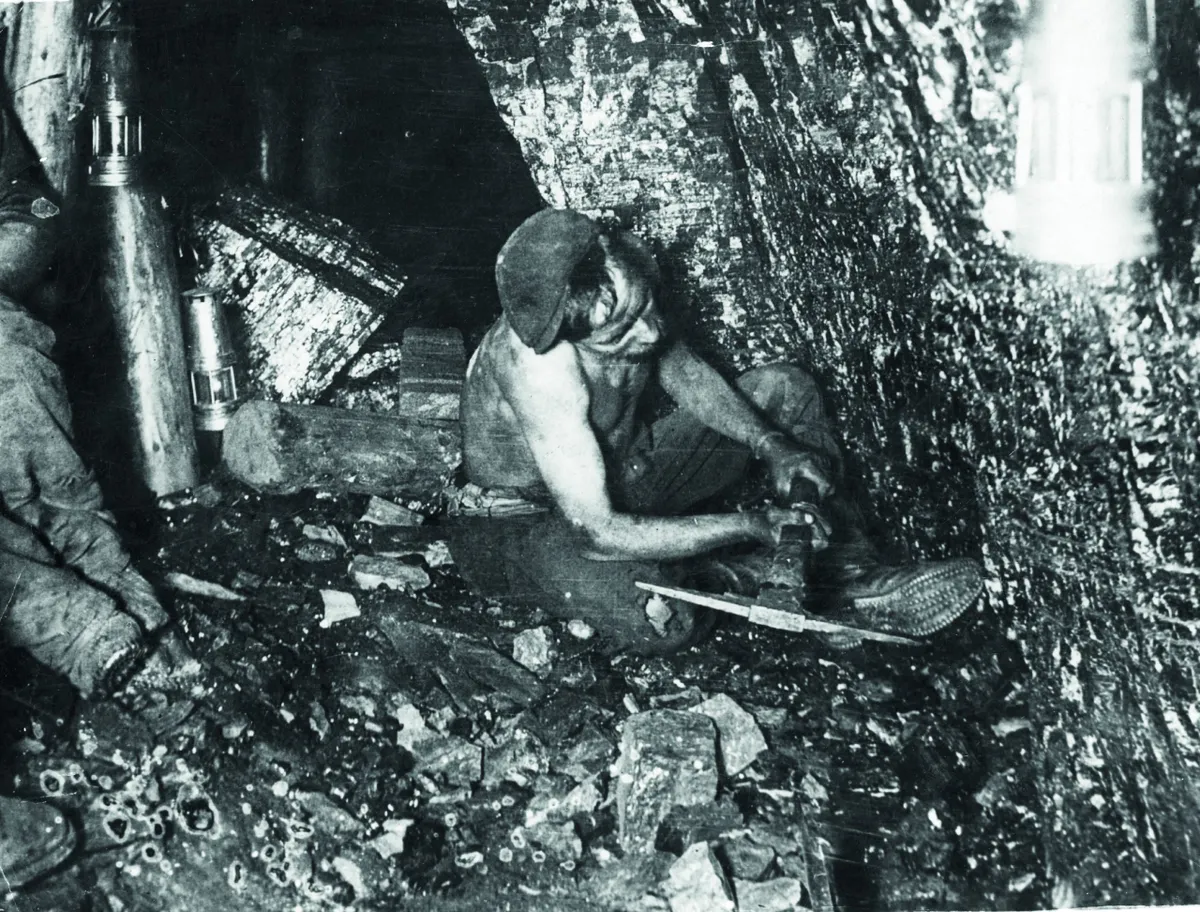

Investigating your ancestors’ occupation gives you more scope for developing an interesting narrative. You can write about what their work involved, what training or uniform was required, what tools would have been used, and what the hazards of that job might have been.

Visit the places where they lived, either in person or on Google Maps. It is important to think about where your relations were living, and to set them in their local historical context. Perhaps there are websites or books that can tell you about life in their town or village. You should make use of the expertise of a relevant local-history society, or someone doing a one-place study of the community where your family lived. Old newspapers are a mine of information about local events as well.

We often believe that national events would not have had much bearing on our ancestors’ lives, but some would have had a significant impact, and can provide hooks to help your audience view the characters against the background of their times. As soon as you say “Queen Victoria” or “the Agricultural Revolution”, this triggers certain associations, so it is useful to provide these pointers, along the lines of “Grandma was six when the First World War broke out”.

Some aspects of national history will be more relevant to particular ancestors than others, so you should prioritise those. You might want to refer to royalty or politics, telling your readers who the monarch or the prime minister was. Write about wars and conflicts that were going on at the time. Would your family have been involved as combatants, or would they have experienced hardships at home?

You might also like to consider what was happening religiously: was this a time of persecution, or rising nonconformity? How about the world of science, technology and inventions? Then there is the arts: what books were being written, what music was being played, what pictures were being painted? You can also note any special events that occurred. Did your ancestor attend the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, take part in the General Strike of 1926, or campaign for the right to vote for women and working-class men?

If this all sounds a bit daunting, take it one ancestor, or small family group, at a time. Begin with a simple timeline of the events in their life: birth, marriage, death, schooling, house moves and so on. You may have family history software that does this for you. Add national and local events to that timeline. Then expand each fact into a paragraph. If the first fact is “Annie Pepperell was born in 1855 in Croydon, Surrey”, there are several questions that you can answer. Was she named for a relative? What was her position in the family? What is the meaning and geographical distribution of her surname? What was happening in 1855, and in Croydon in particular? You can then repeat the process for subsequent facts, and weave in the social history. Congratulations! You now have a story to share.

It will enhance your narrative if you can add illustrations. You will want to include family trees and if possible old photographs of people and places, gravestones, the local church, the ships they sailed on, or the clothes that they might have worn. You may be able to add old maps and facsimile documents too, but remember that just because an image is online, it does not mean that it is free of copyright or can be used without seeking permission.

Finally, you also need to decide the most suitable medium for your story – writing a book or an article is far from the only option. For example, video presentations are increasingly easy to produce. Alternatively, you could create a website, a blog or a podcast. You could even think right outside the box and tell aspects of your family history in art, Lego or needlework. Whatever you decide, make a start and enjoy bringing your ancestors and their times to life.